Lesson 9 The Good Life

Memorizing these ideas is easy. Living them takes a lifetime of practice. Fortunately, the heroes of all time have walked before us. They show us the path.

9.1 Creating “The Good Life”

This book started with an invitation to see your own seeing by stepping out of your culture, biases, and assumptions to see that much of what you take for granted as reality is very different in other cultures. In doing this, we discovered a tremendous wealth of possibility in the human condition – physical capacities we did not know we had, unique and insightful ways of seeing and talking about the world, and different ways of surviving and thriving in many different environments. We also encountered different ways of thinking about love, identity, gender, race, morality, and religion. All of this can seem remarkably liberating, giving us a broader vision of what is possible. As anthropologist and psychologist Ernest Becker once wrote:

“The most astonishing thing of all, about man’s fictions, is not that they have from prehistoric times hung like a flimsy canopy over his social world, but that he should have come to discover them at all. It is one of the most remarkable achievements of thought, of self-scrutiny, that the most anxiety-prone animal of all could come to see through himself and discover the fictional nature of his action world. Future historians will probably record it as one of the great, liberating breakthroughs of all time, and it happened in ours.”

But the discovery of our “fictions” is not because of anthropology. Rather, anthropology is itself a product of larger social and intellectual trends that moved our society away from the shackles of tradition toward the more intentional creation of modern society. In this sense, the ideas, ideals, values, beliefs, and institutions of modern society are constantly under scrutiny for ways in which they might be changed or improved to maximize human flourishing.

Most people would not question the value of these modern projects, and few would want to return to the more rigid traditional hierarchies and moral horizons of older social orders. However, the modern revisions come with a cost. The old orders provided exactly that: order. In order, there is meaning. In a clearly defined social role, there is purpose. In stable institutions, there is a promise for the future. With meaning, purpose, and the future now in question, we cannot help but constantly ask those three big questions: Who am I? What am I going to do? Am I going to make it?

In his landmark book, “Man’s Search for Meaning,” Victor Frankl claims that it is our Will to Meaning that is the dominant human drive, stronger than the Will to Pleasure or any other drive. But he worries that we now live in an “existential vacuum” due to two losses – first, the loss of instincts guiding all of our behavior, forcing us to make choices, and second, the loss of tradition. “No instinct tells him what he has to do, and no tradition tells him what he ought to do; sometimes he does not even know what he wishes to do.”

Compounding the crisis, the last chapter makes it evident that we now live in a time in which it is entirely possible to imagine cataclysmic change so dramatic that it would effectively constitute “the end of the world as we know it.” Nuclear war, climate catastrophes, global economic collapse, and the possibility of totalitarian super-states are ever-present threats, with constant reminders bombarding us throughout the 24-hour news cycle. And so we also must constantly ask those other three big questions: Who are we? What are we going to do? Are we going to make it?

These two sets of questions are interconnected. In order to find a personal sense of purpose in the world, one must have some vision of where the world is going and what would constitute a good and virtuous life. As Anthony Giddens has suggested, personal meaninglessness can become a persistent threat within the contexts of modernity that provide no clear framework for meaning.

Modernity leaves us with two unavoidable projects. First, as Giddens puts it, “the self, like the broader institutional contexts in which it exists, has to be reflexively made. Yet this task has to be accomplished amid a puzzling diversity of options and possibilities.” This “consists in the sustaining of coherent, yet continuously revised, biographical narratives.” Second, we have to choose or create values, virtues, and meanings in a world that does not offer a shared, definitive, unquestioned moral order that could define these things for us. In other words, we are freer than ever to be, do, and think whatever … but when we all make different choices about who we will be, what we will do, and how we will think, we lose a shared system of meanings and values upon which we can find meaning, construct viable identities, and feel a sense of purpose and recognition.

Until recently, anthropology has been mostly silent on questions of “the good life.” While documenting a wide range of different cultures, each of which may define “the good life” in different ways, anthropologists have been hesitant to offer any prescriptions for how one should live. But recent studies are changing that. In this lesson, we will see what anthropology has to tell us that might help us on our own projects of building meaning, setting the stage for your next challenge – to do what you have spent your whole life doing, revising your story and defining your core values.

ARE THERE UNIVERSAL VALUES?

In the late 1990s, psychologists Martin Seligman and Chris Peterson set out to explore the brighter side of human nature. They had grown concerned that psychology was focused only on problems and pathology. They turned instead to the ideas of happiness and human flourishing, and founded the field of positive psychology. One of their first projects was to construct a list of widely shared human values, characteristics, and virtues that would be more or less universally valid and recognized among all cultures. Given the tremendous diversity of cultures in the world, they knew they could not attain true universality, so they settled instead on finding “ubiquitous virtues and values … so widely recognized that an anthropological veto (‘The tribe I study does not have that one!’) would be more interesting than damning.”

They proceeded by brainstorming characteristics they thought might be universal, and then compared them against key texts from Asian and Western religions, world philosophies, and wisdom traditions. An obvious shortcoming of their study is that they did not include any representation from the Americas or Africa other than Islam. Nonetheless, their lists of virtues and positive character traits are an interesting start toward finding some universally agreed upon human virtues and values. The list of 24 character strengths is broken up into six core virtues:

- Wisdom (curiosity, love of learning, judgment, ingenuity, emotional intelligence, perspective)

- Courage (valor, perseverance, integrity)

- Humanity (kindness, loving)

- Justice (citizenship, fairness, leadership)

- Temperance (self-control, prudence, humility)

- Transcendence (appreciation of beauty, gratitude, hope, spirituality, forgiveness, humor, zest)

These six virtues mirror the six foundations of morality established by Jonathan Haidt, and we can see how each virtue might provide evolutionary advantages that ensured our survival. We need wisdom and courage to survive. We need humanity, justice, and temperance to care for one another and work through inevitable social problems. A sense of transcendence (even of the secular sort) can provide us with a sense of meaning, purpose, and joy that motivates us through life.

The virtues are abstract enough to allow for significant cultural difference while still capturing some sense of what all humans value. Jonathan Haidt points out that we cannot even imagine a culture that would value their opposites. “Can we even imagine a culture in which parents hope that their children will grow up to be foolish, cowardly, and cruel?”

Probably not. But there are cultures where someone who is foolish, cowardly, and cruel will be greeted with kindness rather than scorn. Jon Christopher tells a story from his fieldwork in Bali, where a local drunk was constantly causing problems and failing to provide for his family. Instead of people judging him harshly, he was greeted with “pity, compassion and gentleness.” The only way to understand this response is to understand the broader cultural frameworks of the Balinese. They see reality as broken up into two realms; the sekala or ordinary realm of everyday life, and the niskala, a deeper level of reality where the larger dramas of souls, karma, and reincarnation ultimately shape and determine what happens in the ordinary realm. This man deserved pity and compassion because his behavior in sekala was a reflection of the turmoil his soul was facing in niskala.

In fact, most cultures, including Western culture up until the Renaissance and Enlightenment, see the world as broken up into two tiers. One is an all-encompassing cosmological framework that provides meaning and value to the other tier of ordinary day-to-day life. According to philosopher-historian Charles Taylor, the West’s cultural drive to flatten traditional hierarchies and inequalities through the Protestant Reformation, Enlightenment, democracy, and the scientific revolution called these ultimate cosmological frameworks of the top tier into question, and ultimately rendered them arbitrary at best, and at worst, a threat to human freedom and flourishing.

As a result, hierarchies were flattened and the two-tiered world collapsed. We were left with a worldview that places the individual self at the center as the sole arbiter of meaning and value. Our moral system came to champion the individual’s right to choose their own meanings and to pursue happiness however we choose to define it, just as long as we do not impinge on the ability of others to pursue happiness, however they might define it.

Seligman’s list of virtues is in many ways an attempt to use reason and science to discover meanings and values that, by virtue of being universal, might not feel so arbitrary. “I also hunger for meaning in my life that will transcend the arbitrary purposes I have chosen for my life,” Seligman wrote in 2002 as he was working on the inventory of virtues.

Jon Christopher argues that while Seligman’s list is an admirable effort and one worthy of continued discussion and exploration, it is ultimately limited by the Western cultural framework. Remember that Seligman and his colleagues started with a list of virtues, and then tried to find them in other traditions. This had the effect of flattening complex ideas like “wisdom” and “justice” so much that the real wisdom of other traditions was lost in translation.

THE VALUE AND VIRTUE OF OTHER VALUES AND VIRTUES

Christopher points to the example of Chinese philosophy that places five core values at the center of their moral world:

- Role fulfilment.

- Ties of sympathy and concern based on metaphysical commonalities.

- Harmony.

- Culmination of the learning process.

- Co-creativity with heaven and earth.

The contrast with Seligman’s list is profound. In fact, “role fulfilment,” which is a common value throughout much of the world, is not highlighted in any of Seligman’s character strengths. But at an even deeper level, values that are based on “metaphysical commonalities” and “co-creativity of heaven and earth” signal a very different cosmological framework and, in fact, a different theory of being itself. Specifically, the Chinese virtues depend on a two-tiered model that places value on serving and maintaining the upper tier that provides meaning and significance, while Seligman’s list depends on a cultural framework centered on individualism and the self.

Other research indicates that cultures live in a different emotional landscape. For example, in Japan the emotion of amae is often translated as a desire for indulgence or dependence. It is the feeling a twelve year-old child might have in asking a parent to “baby” them by tying their shoes. According to Takeo Doi, who first introduced the concept of amae to the Western world, the full experience of the emotion depends upon a larger cultural context that values interdependence and harmony, so there can be no adequate translation into the Western context.

Many traditions suggest that the self is in itself the problem. Hinduism suggests that enlightenment can only occur when one recognizes that the self (Atman) is one and the same as the Absolute all or Godhead (Brahman). Buddhism goes a step further by suggesting the concept of anatman or “non-self,” which denies the existence of any unchanging permanent self, soul, or essence. Taoism suggests that one must put one’s self in accord with the “tao” or way of all things. This “way” is beyond words and cannot be spoken about. It can only be known through living in accord with the “way” of life, nature, and the universe. In all of these traditions, the “self” as it is normally celebrated in the West is a hindrance to the good life.

Western psychology tends to judge “the good life” with measures of subjective well-being (often referred to in the literature as SWB). Research participants are asked to rate items such as “In most ways my life is close to my ideal” or “I am satisfied with my life.” But in many other cultures, what is “ideal” cannot and should not be determined by the individual, and subjective well-being is not necessarily “good.” For example, in many non-Western cultures, negative emotions are valued as a sign of virtue when they alert the person to how they are not living in alignment with their role or social expectations. Measurements of subjective well-being often fail in cross-cultural contexts, because subjects refuse to consult their own subjective feelings to assess whether or not something is good. They tend to evaluate the good based on larger cosmological and social frameworks rather than their own personal experience.

But the modern West is not the first worldview to do away with the “second tier” and leave it to individuals to try to construct values and meaning. When Siddhartha Gautama Buddha laid out the original principles of Buddhism he did so in part as a critique of wheat he saw as a corrupt Hinduism in which authority was abused, ritual had become empty and exploitative, explanations were outdated, traditions were irrelevant to the times, and people had become superstitious and obsessed with miracles. Cutting through the superstition and corruption, the Buddha offered a philosophy that required no supernatural beliefs, rituals, or theology. Instead, he offered a set of practices and a practical philosophy (which together make up the eightfold path) that can lead to one living virtuously.

Of utmost importance to virtue in the original Buddhism was the idea that it is not enough simply to know what is virtuous or to “hold” good values. It is easy to know the path. It is much more difficult to walk the path. Therefor Buddha offered practices of mindfulness and meditation to quiet selfish desire, center the mind, and help people live up to their values.

The Buddha saw the source of human suffering in misplaced values. People want wealth, status, praise, and pleasure. But all of these are impermanent and out of one’s control. In desiring them, we set ourselves up for disappointment, sadness and suffering. As Buddha teaches in the teaching of the eight worldly winds, “gain and loss, status and disgrace, blame and praise, pleasure and pain: these conditions amount human beings are ephemeral, impermanent, subject to change. Knowing this, the wise person, mindful, ponders these changing conditions. Desirable things don’t charm the mind, and undesirable ones bring no resistance.”

The goal of Buddhist practice is to only desire the narrow path of mindful growth and development and to shrink selfish egotistical desires. As such, the practitioner comes to desire what is best for the world, not what is best for the self, and then feels a sense of enlightened joy and purpose.

The ancient Western world also offers an example of a tradition that did away with the “second tier” in Stoicism, which flourished in Greece and Rome from the 3rd century BC to the 3rd century AD. While the Stoics did believe in God, they saw God not as a personified entity but as the natural universe itself imminent in all things. In order to understand God, they had to understand nature, making the study of nature and natural law essential to living a good and virtuous life.

Despite notable differences with Buddhism, the Stoics developed a similar method for arriving at good values and virtues. In short, we should not value those things that are out of our control. As Stoic philosopher Epictetus summed it up, “Some things are up to us, and some things are not up to us. Our opinions are up to us, and our impulses, desires, aversions – in short, whatever is our own doing. Our bodies are not up to us, nor are our possessions, our reputations, or our public offices, or that is, whatever is not our own doing.”

Such words and the foundational philosophy of stoicism were essential to Victor Frankl as he endured the horrors of concentration camps in WWII. In the midst of unimaginable suffering, starvation, humiliation, and death he found a place to practice his “Will to Meaning” by recognizing the Stoic truth of detaching from what is out of his control, and instead working to control what he could – his thoughts. He and his fellow prisoners “experienced the beauty of art and nature as never before,” he writes. “If someone had seen our faces on the journey from Auschwitz to a Bavarian camp as we beheld the mountains of Salzburg with their summits glowing in the sunset, through the little barred windows of the prison carriage, he would never have believed that those were the faces of men who had given up all hope of life and liberty.”

Stoicism has had a big impact on modern psychology, forming the philosophical foundations of Frankl’s Logotherapy and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, the most common form of therapy now used in clinical psychology.

At the center of both Buddhist and Stoic practice is recognizing that emotions are simply signals that can be observed and acted upon, but are not “good” or “bad” in themselves. Such emotions can be observed, which disempowers them, allowing an inner calm to develop. Freed from emotional reasoning, a person is more capable of living virtuously even in the face of complexity, conflict, and turmoil.

In colloquial terms, Mark Manson calls it (in the title of his best-selling book) “The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck.” Influenced by Buddhist and Stoic philosophy, Manson notes that the idea is not that one should be indifferent, but that we have to be careful about what we choose to “give a f*ck about” – or in other words, we have to choose our values – “what you’re choosing to find important in life and what you’re choosing to find unimportant.” Manson does not shy away from the fact most people in the West will deny all-encompassing cosmological frameworks as questionable and arbitrary, which means we cannot help but choose our values. However, we can use the basic tenets from different wisdom traditions such as Stoicism and Buddhism to help us evaluate our values.

Manson arrives at three principles for evaluating values. They should be:

- Based in reality.

- Socially constructive.

- Within our immediate control.

Many of the most common values held by people, such as pleasure, success, popularity, and wealth, are not good values, because they are either socially destructive or not in our immediate control. Studies show that people who pursue pleasure end up more anxious and prone to depression. Short-term pleasure just for the sake of pleasure can also lead to dangerous addictions or impulsive behaviors that can lead to long-term trouble.

Good values include character traits that are socially constructive and within our control. These would include honesty, self-respect, charity, and humility as well as many of the items on Seligman’s original list, such as curiosity and creativity. But importantly, Manson suggests that these values should not be judged on whether or not they “feel good.” One should be honest even when it hurts, humble even if it means forgoing praise and pleasure.

Ironically, it may be our individualistic focus on positive emotions and the pursuit of happiness that make it so difficult to achieve positivity and happiness. As Manson observes, “Our society today … has bred a whole generation of people who believe that having these negative experiences – anxiety, fear, guilt, etc. – is totally not okay.” As he poignantly observes, “the desire for more positive experience is itself a negative experience. And paradoxically, the acceptance of one’s negative experience is itself a positive experience.”

This reflects a more profound vision of life in which avoiding problems and pain is not necessarily good. Instead, problems and pain become tools and opportunities for change. But studies show that in order to get the most out of our problems and pain, we have to find ways to make sense of them. We have to make meaning.

ANTHROPOLOGY OF THE GOOD LIFE

In a recent study sure to become a landmark in anthropology, Edward Fischer sets out to study ideas of “the good life” in the supermarkets of Hannover, Germany and the coffee farms of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. The two could hardly be further apart, geographically, culturally, and economically. The Guatemalans live with just 1/8 of the income of the Germans, but even worse, must suffer the violence of drug trafficking, creating one of the highest murder rates in the world.

Though the cultural context varies tremendously, Fischer still finds common concerns and themes where visions of the good life overlap. He suggests that these may form the foundation for a “positive anthropology” similar to positive psychology. But while positive psychologists like Seligman and Peterson list internal individualistic character traits or virtues that we should cultivate, Fischer instead finds five elements that a culture or society should aspire toward to ensure that everyone has adequate opportunity to pursue virtue however they might define it. Every society should provide:

- Aspiration (hope)

- Opportunity: power to act on that aspiration

- Dignity

- Fairness

- Commitment to Larger Purposes

The list provides an interesting alternative to the current mode of judging cultures and countries based primarily on their Gross Domestic Product (GDP). As anthropologist Arjun Appadurai notes, the “avalanche of numbers – about population, poverty, profit, and predation” provides a limited view of the world that denies local perspectives. Instead, he advocates more nuanced ideas of the “good life” based on local ideals.

Fischer hopes that a turn in this direction could allow anthropologists to investigate and make suggestions about which cultural norms, social structures, and institutional arrangements foster wellbeing in different contexts. It is an inspiring idea. What if, instead of just trying to maximize wealth, we tried to maximize hope, opportunity, dignity, fairness, and purpose?

“It takes more than income to produce wellbeing,” Fischer concludes, “and policy makers would do well to consider the positive findings of anthropology and on-the-ground visions of the good life in working toward the ends for which we all labor.”

LEARN MORE

The Good Life: Aspiration, Dignity, and the Anthropology of Wellbeing, by Edward Fischer

Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being, by Martin Seligman

“Positive Psychology, Ethnocentrism, and the Disguised Ideology of Individualism,” by John Chambers Christopher and Sarah Hickinbottom.

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck, by Mark Manson

The Dhammapada. Translated by Eknath Easwaran

Man’s Search for Meaning, by Victor Frankl

How to be a Stoic, by Massimo Pigliucci

9.2 The Power Of Storytelling

On my first day of graduate school, I watched my new advisor, Roy Wagner, walk onto the stage in front of 200 undergraduates in his Anthropology of Science Fiction class and drop-kick the podium. The podium slid across the stage and crashed to the floor. But Roy was not yet satisfied. He picked up the podium and hurled it off the stage and launched into a tirade. He said he had heard a story that dozens of students had decided to take the class because they thought it would be an “easy A.” He wanted to assure them that this wasn’t the case, and invited anyone who was not fully committed to leave the room immediately. A couple dozen people walked out. Then he calmly picked up the podium, set it back up, warmly welcomed us to the class, and then proceeded to share with us “the secret” of anthropology: “Anthropology is storytelling.”

He proceeded to reveal the importance of anthropology in crafting the storyworlds of classic Science Fiction texts like Dune and The Left Hand of Darkness (written by Ursula Le Guin, the daughter of Alfred Kroeber, one of the most famous anthropologists of all time). But more importantly, he showed us the importance of storytelling in understanding and presenting the cultural worlds and life stories of others. As anthropologist Ed Bruner noted, “Our anthropological productions are our stories about their stories; we are interpreting the people as they are interpreting themselves.”

Of course, the real insight here is that we are all always “anthropologists,” in the sense that all of us are interpreting the stories of people around us, and the stories people tell about themselves are also simplified interpretations of a very complex history and web of deeply entangled experiences. But we are not just interpreting the stories of others, we are also constantly telling and retelling the story of our own selves. “Yumi stori nau!” is the most common greeting you will hear as you walk around Papua New Guinea. The direct English transliteration: “You Me Story Now!” perfectly captures the spirit of the request. It is an expression of the joy felt when two people sit down and share stories together. In Nimakot, where there are no televisions or other media forms, storytelling is king, just as it has been for most humans throughout all time.

Among the Agta, hunter-gatherers in the Philippines, anthropologist Andrea Migliano found that when the Agta were asked to name the five people they would most like to live with in a band, the most sought-after companions were the great storytellers. Being a great storyteller was twice as important as being a great hunter. And this wasn’t just for the high-quality entertainment. Storytellers had a profound influence on the well-being of the group. Stories among the Agta often emphasize core cultural values such as egalitarianism and cooperation. So when Migliano’s team asked different Agta groups to play a game that involved sharing rice, the groups with the best storytellers also turned out to be the most generous and egalitarian in their sharing practices.

The storytellers were also highly valued for the cultural knowledge that they possess and pass on to others. Societies use stories to encode complex information and pass it on generation after generation.

As an example, consider an apparently bizarre and confusing story among the Andaman Islanders about a lizard that got stuck in a tree while trying to hunt pigs in the forest. The lizard receives help from a lanky cat-like creature called a civet, and they get married. What could this possibly mean? Why is a lanky cat marrying a pig-hunting lizard? Such stories can provide a treasure of material for symbolic interpretation, but the details of such stories also pass along key information across generations about how these animals behave and where they can be found. As anthropologist Scalise Sugiyama has pointed out, this is essential knowledge for locating and tracking game.

One especially provocative and interesting anthropological theory about storytelling comes from Polly Wiessner’s study of the Ju/’hoansi hunter-gatherers of southern Africa. While living with them, it was impossible not to notice the dramatic difference between night and day. The day was dominated by practical subsistence activities. But at night, there was little to be done except huddle by the fire.

The firelight creates a radically different context from the daytime. The cool of the evening relaxes people, and if the temperatures drop further they cuddle together. People of all ages, men and women, are gathered together. Imaginations are on high alert under the moon and stars, with every snap and distant bark, grumble or howl receiving their full attention. The light offers a small speck of human control in an otherwise vast unknown. They feel more drawn to one another, and the sense of a gap between the self and the other diminishes.

It is in this little world around the fire where the stories flow. During the day just 6% of all conversations involve storytelling. Practical matters rule the day. But at night, 85% of all conversation involves storytelling or myth-telling. As she notes, storytelling by firelight helps “keep cultural instructions alive, explicate relations between people, create imaginary communities beyond the village, and trace networks for great distances.”

Though more research still needs to be done, her preliminary work suggests that fire did much more for us than cook our food in the past. It gave us time to tell stories to each other about who we were, where we came from, and the vast networks of relations that connect us to others. The stories told at night were essential for keeping distant others in mind, facilitating vast networks of cooperation, and building bigger and stronger cultural institutions, especially religion and ritual. Fire sparked our imaginations and laid the foundation for the cultural explosion we have seen over the past 400,000 years.

STORIES ARE EVERYWHERE

Stories are everywhere, operating on us at every moment of our lives, but we rarely notice them. Stories provide pervasive implicit explanations for why things are the way they are. If we stop to think deeply, we are often able to identify several stories that tell us about how the world works, the story of our country, and even the story of ourselves. Such stories provide frameworks for how we assess and understand new information, provide a storehouse of values and virtues, and provide a guide for what we might, could, or should become. Most importantly, they do not just convey information, they convey meaning. They bring a sense of significance to our knowledge.

Stories are powerful because they mimic our experience of moving through the world – how we think, plan, act, and find meaning in our thoughts, plans, and actions.

We are in a constant process of creating stories. When we wake up, we construct a narrative for our day. If we get sick, we construct a narrative for how it happened and what we might be able to do about it. Through a wider lens, we might look at the story of our lives and construct a narrative for how we became who we are today, and where we are going. Through an even broader lens, we construct stories about our families, communities, our country, and our world.

Cultures provide master narratives or scripts that tell us how our lives should go. A common one for many in the West is go to school, graduate, get a job, get married, have kids, and then send them to college and hope they can repeat the story. But what happens when our lives go off track from this story? What happens when this story just doesn’t work for us? We find a new story, or we feel a little lost until we find one. We can’t help but seek meaning and coherence for our lives.

What is the story of the world? Most people have a story, often unconscious, that organizes their understanding of the world. It frames their understanding of events, gives those events meaning, and provides a framework for what to expect in the future.

Jonathan Haidt proposes that most Westerners have one of two dominant stories of the world that are in constant conflict. One is a story that frames Capitalism in a negative light. It goes like this:

“Once upon a time, work was real and authentic. Farmers raised crops and craftsmen made goods. People traded those goods locally, and that trade strengthened local communities. But then, Capitalism was invented, and darkness spread across the land. The capitalists developed ingenious techniques for squeezing wealth out of workers, and then sucking up all of society’s resources for themselves. The capitalist class uses its wealth to buy political influence, and now the 1% is above the law. The rest of us are its pawns, forever. The end.”

In the other story, capitalism is viewed positively, as the key innovation that drives progress and lifts us out of poverty and human suffering. It goes like this:

“Once upon a time, and for thousands of years, almost everyone was poor, and many were slaves or serfs. Then one day, some good institutions were invented in England and Holland. These democratic institutions put checks on the exploitative power of the elites, which in turn allowed for the creation of economic institutions that rewarded hard work, risk-taking, and innovation. Free Market Capitalism was born. It spread rapidly across Europe and to some of the British colonies. In just a few centuries, poverty disappeared in these fortunate countries, and people got rights and dignity, safety and longevity. Free market capitalism is our savior, and Marxism is the devil. In the last 30 years, dozens of countries have seen the light, cast aside the devil, and embraced our savior. If we can spread the gospel to all countries, then we will vanquish poverty and enter a golden age. The end.”

You probably recognize both of these stories. They operate just beneath the surface of news articles, academic disciplines, and political movements. If we pause, think deeply, and take the time to research, we would probably all recognize that both stories offer some insights and truth, but both are incomplete and inaccurate in some respects.

Haidt proposes that we co-create a third story that recognizes the truths of both stories while setting the stage for a future that is better for everybody. His proposal is a reminder that once we recognize the power of stories in our lives, we also gain the power to recreate those stories, and thereby recreate our understanding of ourselves and our world.

THE WISDOM OF STORIES

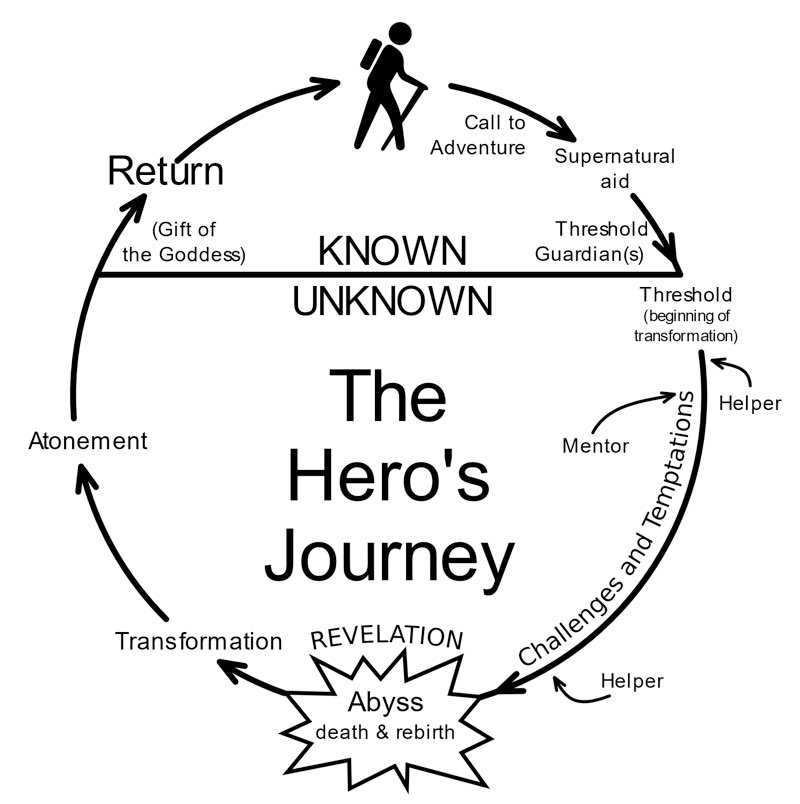

During the Great Depression, Joseph Campbell spent five years in a small shack in the woods of New York reading texts and stories from religious traditions all over the world. As he did so, he started to see common underlying patterns to many of the stories, and a common body of wisdom. One pattern he found was that of the hero’s journey. All over the world, he found stories of heroes who are called to adventure, step over a threshold to adventure, face a series of trials to achieve their ultimate boon, and then return to the ordinary world to help others.

He mapped out the hero’s journey in a book appropriately titled The Hero with a Thousand Faces in 1949. The book would ultimately transform the way many people think about religion, and have a strong influence on popular culture, providing a framework that can be found in popular movies like Star Wars, The Matrix, Harry Potter, and The Lion King. The book was listed by Time magazine as one of the 100 best and most influential books of the 20th century.

In an interview with Bill Moyers, Campbell refers listeners to the similarities in the heroic journeys of Jesus and Buddha as examples:

Jesus receives his call to adventure while being baptized. The heavens opened up and he heard a voice calling him the son of God. He sets off on a journey and crosses the threshold into another world, the desert, where he will find his road of trials, the three temptations. First Satan asks him to turn stones into bread. Jesus, who has been fasting and must be very hungry, replies, “One does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God.” Satan takes him to the top of the temple and asks him to jump so that the angels may catch him, and Jesus says, “You shall not put the lord, your God, to the test.” Then Satan takes Jesus to a high mountain from which all the kingdoms of the world can be seen. He promised Jesus he could have all of it “if you will fall down and worship me.” Jesus says, “Away, Satan! For it is written;”Worship the Lord your God and serve him only.” The devil left him, and angels appeared to minister to him.

He had conquered fear and selfish desire and received his ultimate boon: wisdom and knowledge that he would spread to others.

Born a prince, Siddhartha lived a luxurious life behind palace walls, protected from the pain and suffering of the world. But at age 29 he made his way past the place walls and encountered old age, sickness, and death. Seeing this he set out to find peace and understand how one is to live with this ever-present reality of human suffering. He found many teachers and patiently learned their beliefs, practices and meditations but he still felt unsatisfied. He set off alone and came to rest under a tree. There it was that Mara, the evil demon, gave him three trials. First, he sent his three daughters to seduce him. But Siddhartha was still and without desire. Then Mara sent armies of monsters to attack Siddhartha. But Siddhartha was still and without fear. Then Mara claimed that Siddhartha had no right to sit in the seat of enlightenment. Siddhartha was still and calmly touched the earth with his hand and the earth itself bore witness to his right.

He had conquered fear and selfish desire and received his ultimate boon: wisdom and knowledge that he would spread to others.

Both stories tell the tale of a hero who is unmoved by the selfish and socially destructive values of wealth, pleasure, and power to serve a higher purpose. Campbell was struck by ubiquitous themes he found across cultures in which people overcome basic human fears and selfish desires to become cultural heroes. In his book, he identified 17 themes that are common throughout hero stories around the world. They’re not all always present, but they are common. Seven of them are especially prominent and essential:

- The Call to Adventure. The hero often lives a quintessentially mundane life, but longs for something more. Something happens that calls the hero forth into the adventure. The hero often hesitates but eventually accepts the call.

- The Mentor. There is usually someone who helps the hero as he crosses the threshold into the land of adventure.

- The Trials. The hero must face many tests and trials, each one offers a lesson and helps the hero overcome fear.

- “The Dragon.” The hero’s biggest fear is often represented by a dragon or some kind of ultimate threat.

- The Temptations. There are usually some temptations trying to pull the hero away from the path. These test the hero’s resolve and ability to quell their selfish desires.

- The Ultimate Temptation: The ultimate temptation is usually the demand of social life, a “duty” we feel to be and act in a certain way that is not in alignment with who we really are.

- Ultimate Boon. If the hero can move past fear and desire, he is granted a revelation and transforms into a new being that can complete the adventure.

That the same basic structure can be found all over the world in both story and ritual illuminates profound universals of the human condition. Specifically, all humans are born unfinished and in a state of dependency, and must make a series of major changes in identity and role throughout life. Hero stories highlight the key dilemmas we all must face.

But as Campbell studied the stories and traditions of the world, he became more and more concerned that modern society had lost its connection to the key wisdom and guidance that hero stories could provide. He worried that literal readings of the heroic stories in the Bible were not appealing to many people, because the core stories are based in a society of the Middle East 2,000 years ago when slavery was commonplace and women were not equals. Back then it was common to assume, as described in Genesis, that the world is relatively young, perhaps just a few thousand years old, and is shaped like a flat disc with a dome above it – the firmament of heaven – that holds the stars.

Such stories are hard to square with our current knowledge that the earth is over 4 billion years old and sits on the outer edge of a vast galaxy which is itself just a small piece of a larger universe that is about 14 billion years old.

As a result, Campbell lamented, both Christians and atheists do not receive the potential wisdom of religious stories because they are overly focused on whether or not the stories are true rather than trying to learn something from them.

Campbell called on artists to develop new stories that could speak to the challenges of our times and serve the four functions of religion outlined earlier – stories that could teach us how to live a good life in today’s world (the pedagogical function), stories that could help us get along and feel connected to one another (the sociological function), stories that could give us a better picture and understanding of how things work today (the cosmological function), and stories that could allow us to feel hopeful and stand in awe of the universe (the mystical function).

George Lucas was one of the first to hear the call.

REBIRTH OF THE HERO

Lucas came across Campbell’s work while he was working on Star Wars. “It was a great gift,” Lucas said, “a very important moment. It’s possible that if I had not come across that I would still be writing Star Wars today.” Thanks to Campbell’s work, the stories of Jesus, Buddha, and other religious hero stories from all over the world came to influence characters like Luke Skywalker. George Lucas would refer to Campbell as “my Yoda,” and the influence of the great teacher is evident in the work.

Star Wars was just the first of many Hollywood movies that would use the hero cycle as a formula. In the mid-1980s Christopher Vogler, then a story consultant for Disney, wrote up a seven-page memo summarizing Campbell’s work. “Copies of the memo were like little robots, moving out from the studio and into the jetsream of Hollywood thinking,” Vogler notes. “Fax machines had just been invented … copies of The Memo \[were\] flying all over town.”

Movies have become the new modern myths, taking the elements of hero stories in the world’s wisdom traditions and placing them in modern day situations that allow us to think through and contemplate contemporary problems and challenges. In this way, elements of the great stories of Jesus and Buddha find their way into our consciousness in new ways.

Movies like The Matrix provide a new story that allows us to reflect on our troubled love-hate codependency-burdened relationship to technology. The hero, Neo, starts off as Mr. Anderson, a very ordinary name for a very ordinary guy working in a completely nondescript and mundane cubicle farm. His call to adventure comes from his soon-to-be mentor, Morpheus, who offers him the red pill. Mr. Anderson suddenly “wakes up,” literally and figuratively, and recognizes that he has been living in a dream world, feeding machines with his life energy. Morpheus trains him and prepares him for battle. Morpheus reveals the prophecy to Neo, who, Morpheus calls “The One” – the savior who is to free people from the Matrix and save humankind. (The name “Neo” is “One” with the O moved to the end of the word.) In this way, Neo’s story is very much like the story of Jesus. At the end of the movie, he dies and is resurrected, just like Jesus; but here the story takes a turn toward the East, as upon re-awakening Neo is enlightened and sees through the illusion of the Matrix, just as Hindus or Buddhist attempt to see through the illusion of Maya.

The religious themes continue in the second movie, as Neo meets “the architect” who created the Matrix. The architect looks like a bearded white man, invoking common images of God in the West. But invoking Eastern traditions, the architect informs Neo that he is the sixth incarnation of “The One” and is nothing more than a necessary and planned anomaly designed to reboot the system and keep it under control. Neo is trapped in Samsara, the ongoing cycles of death, rebirth, and reincarnation.

In order to break the cycle, Neo ultimately has to give up everything and give entirely of himself – the ultimate symbol of having transcended desire. In a finale that seems to tie multiple religious traditions together, Neo lies down in front of Deus Ex Machina (God of the Machines) with his arms spread like Jesus on the cross, ready to sacrifice himself and die for all our sins. But this is not just a Christian ending. Invoking Eastern traditions, he ends the war by merging the many dualities that were causing so much suffering in the world. Man and machine are united as he is plugged into the machines’ mainframe. And even good and evil are united as he allows the evil Smith to enter into him and become him. In merging the dualities, all becomes one, and the light of enlightenment shines out through the Matrix, destroying everything, and a new world is born.

The Matrix is an especially explicit example of bringing the themes of religious stories into the modern myths of movies, but even seemingly mundane movies build from the hero cycle and bring the wisdom of the ages to bare on contemporary problems. The Secret Life of Walter Mitty explores how to find meaning in the mundane world of corporate cubicles, and how to thrive in a cold and crass corporate system that doesn’t seem to care about you. The Hunger Games explores how to fight back against a seemingly immense and unstoppable system of structural power where the core exploits the periphery, and how to live an authentic life in a Reality TV world that favors superficiality over the complexities of real feelings and real life. And Rango, which appears to be a children’s movie about a pet lizard who suddenly finds himself alone in the desert, is a deep exploration of how to find one’s true self.

All these stories provide models for how we might make sense of our own lives, and as we will see in the concluding section to this lesson, incorporating what we learn from fictional heroes can have very real effects on our health and well-being.

MAKING MEANING

We all have a story in mind for how our life should go, and when it doesn’t go that way, we have to scramble to pick up the pieces and find meaning. Gay Becker, Arthur Kleinman, and other anthropologists have explored how people reconstruct life narratives after a major disruption like an illness or major cultural crisis. This need for our lives to “make sense” is a fundamental trait of being human, and so we find ourselves constantly re-authoring our biographies in an attempt to give our lives meaning and direction.

Psychologist Dan McAdams has studied thousands of life stories and finds recurring themes and genres. Some people have a master story of upward mobility in which they are progressively getting better day by day. Others have a theme of “commitment” in which they feel called to do something and give themselves over to a cause to serve others. Some have sad tales of “contamination” as their best intentions and life prospects are constantly spoiled by outside influences, while others are stories of triumph and redemption in the face of adversity.

These studies have shown that “making sense” is not just important for the mind; “making sense” and crafting a positive life story have real health benefits. When Jamie Pennebaker looked at severe trauma and its effects on long-term health, he found that people who talked to friends, family, or a support group afterward did not face severe long-term health effects. He suspected that this was because they were able to make sense of the trauma and incorporate it into a positive life story. In a follow up study, he asked one group to journal about the most traumatic experience of their lives for fifteen minutes per day for four days. In the control group, he asked them to write about another topic. A year later, he looked at medical records and found that those who had written about their trauma were less likely to get sick.

This was a phenomenal result, so Pennebaker looked deeper into what people had written during that time. There he found that the people who received the greatest health benefit were those who had made significant progress in making sense of their past trauma and experiences. They had re-written the story of their lives in ways that accommodated their past trauma.

McAdams and his colleagues have found that when people face the troubles and trials of their lives and take the time to make sense of them, they construct more complex, enduring, and productive life stories. As a result, they are also more productive and generative throughout their lives, and have a stronger sense of well-being.

But how do we craft positive stories in the face of adversity and find meaning and sense in tragedy and trauma? There are no secret formulas. People often find their stories of redemption by listening with compassion to the stories of others. In other words, they simply adopt the core anthropological tools of communication, empathy, and thoughtfulness to open themselves up to the stories of others. This is what makes our own life stories, as well as the legends and hero stories written into our religions and scripted on to the big screen so powerful and important. It’s why we sat up by flickering fires for hour after hour for hundreds of thousands of years, and why we still find wisdom in the flickering images of movies and television shows.

LEARN MORE

“Embers of Society: Firelight talk among the Ju/’hoansi Bushmen,” by Paul Wiessner. PNAS 111(39):14027-14035.

The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human, by Jonathan Gottschall

The Power of Myth, by Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers. Book and Video.

The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom, by Jonathan Haidt

What Really Matters: Living a Moral Life amidst Uncertainty and Danger, by Arthur Kleinman

9.3 Challenge Nine: Meaning-Making

Your challenge is to leverage what you learned in this lesson to make meaning by defining your values or re-writing your story of yourself or the world.

Objective: Reflect on your values, your past, or the world and take responsibility for the type of meaning you will make in your life and in the world.

Option 1: Define Your Values

Assess your current values and ideals and use the wisdom outlined in lesson nine to intentionally create and defend a set of core values.

Option 2: Rewrite Your Story

Use the hero story structure to rethink the obstacles, problems, or pains of your life in a way that makes sense of meaning.

Option 3: Rewrite the World

Take Jonathan Haidt up on his challenge to write a “third story” that explains the history, problems, and paradoxes of the world in such a way that provides a meaningful way for you to live in it.

Go to anth101.com/challenge9 to download a worksheet to get you started.