Love In Four Cultures

Nimakot Village, Papua New Guinea

Late one morning, a large argument broke out in the central clearing of the village. A young man and woman named Matius and Rona sat looking dejected and ashamed near the center of the scuffle. The two teenagers had been discovered sneaking off together the previous night, and had been dragged into the clearing by their families. Rona’s brother sat next to her, armed with his 29-inch machete, and looked menacingly at Matius. Matius averted his eyes and stared down at the ground, picking at the grass with his fingers as the chaos of the argument swirled around him. Rona’s mother stormed across the lawn, demanding that the boy’s family give her a large pig. Others from the girl’s family nodded with approval and encouraged her to continue. I sat with a group of locals about 20 meters away from the main action. One of the local women turned to me with a tear in her eye as the argument escalated. Crying with tears of joy, like a mother watching her own daughter on her wedding day, she said, “This is just like when I got married!”

There are no formal ritual “weddings” in this part of New Guinea, but events like this often mark the moment that a man and woman announce their commitment to one another. By the end of the vigorous discussion, the “bride price” had been set. Matius would need to give the bride’s family 95 items such as string bags, clothes, and machetes. At a total market value of nearly $3,000 USD, the request was many times the amount of wealth of any typical villager. He would have to call upon his entire family for help, but even that would not be enough. The challenge of building such a tremendous amount of wealth would become an all-consuming and tremendously stressful task for the next several years of his life. At stake was his entire future – children, family, respect – even his most basic sense of manhood.

Maasai Boarding School, Kenya

When Esther was 14, she learned that her father planned to give her away in marriage to an older man. She ran away to her older sister’s house, who helped her enroll in a school far away. But her father rushed the wedding plans, and her mother tracked her down and removed her from the school. Still hoping that she could escape the arranged marriage, she went to the District Officer, who told her about a rescue center sponsored by an international aid team that hopes to save young girls like Esther from early marriage and give her a chance at school.

Her father came to the rescue center to retrieve Esther, but the headmistress would not allow it, declaring Esther “a school child.” Her father disowned her on the spot. He replayed the scene to anthropologist Caroline Archambault. “Esther will be your child,” he told the school. “You will give her a husband and she will never set foot in my house again.”

Madurai Village, Tamil Nadu, South India

For as long as Mayandi could remember, there was only one right girl for him, his cousin. As the firstborn boy in a Kallar family of the Tamil, it was not only his right, but also “the right thing to do” to marry his mother’s brother’s daughter. The girl was quite literally the right girl for him, and they had a word for it, “murai.”

Mayandi understood that it might seem cruel to an outsider unfamiliar with their customs that someone should be forced to marry someone. As he told American anthropologist Isabel Clark-Decés about their customs, he joked that the “right” person is not always “all right.” Young Tamil girls would often tease each other about the “right” boys they were destined to marry. Mayandi struck the pose of a young girl talking to her girlfriend and joked, “Runny Nose is here to see you!” or “Eggshell Eyes is at your door!”

But Mayandi, like many other young Tamil, came to love and desire his “right” girl very much. It would bring status and honor to the family to marry her. His in-laws would not be strangers and would always feel welcomed in his house. He imagined a wonderful life for himself, his bride-to-be, and their growing family.

But tragedy struck as they approached marriageable age. The bride-to-be’s father got involved in a deadly fight that sent him off to prison, and she had to move into the city. Mayandi was desperate to still make things work out and pressed his mother to arrange the marriage, but it wasn’t to be. She married another man two years later.

Mayandi was devastated. He refused to marry for the next 20 years. Finally, after much pressure from his family, he relented and married his sister’s daughter. They now have two children.

Edinburgh, Scotland

Rabih is not worried about collecting money so that he can pay for a bride. He is not worried about his sister being pulled out of school and being forced to marry a man against her will, and he would never dream of marrying his cousin. Rabih has his own set of troubles as he pursues love and marriage.

Rabih is “in love,” as they say in his culture. As he sits in his room daydreaming about her, his mind wanders to fantasies of their future together. He lets his mind run free and wonders whether or not she might be “the One,” his “soul mate” who will “complete him.” It is his highest ideal, and the thing he wants more than anything in his life.

Feelings of passionate love are not unknown throughout the world. Anthropologists have documented them in nearly every culture they have studied, and have found evidence for romantic love going back thousands of years. But there is something historically and culturally unique about the feelings of people like Rabih. In the words of philosopher Allain de Botton, who tells the story of Rabih in The Course of Love, finding and falling in love “has been allowed to take on the status of something close to the purpose of life,” and this feeling should be the foundation upon which a marriage should be built. “True love” is everlasting, and thought to be the most important part of a good marriage. If passion fades, it was not “true love.”

This is precisely what worries Rabih. He has been in love before. He has hurt and been hurt. How can he be sure that this is the one? How can he make sure that their passion for one another will continue to burn?

In this chapter, we’ll explore love and marriage in four different cultures. In order to understand their radically different ideas, ideals, and practices, we will have to use our anthropological tools for seeing our own seeing, seeing big, seeing small, and seeing it all. We’ll have to examine many different dimensions of culture – infrastructure, social structure, and superstructure – to see how they all come to bear on ideas and practices of love and marriage.

Culture, as we have seen in the preceding chapters, is a powerful structure, but this structure is con-structed. The structure is nothing but the total sum of all of our actions, habits, ideas, ideals, beliefs, values and practices, no matter how big or small. A cultural structure is a powerful force in our lives. It provides the context and meaning for our lives. But, at the same time, our collective actions make the structure.

We make the structure.

The structure makes us.

This exploration will not only help us understand how different cultural realities get “real-ized,” but might also help us understand our own realities in new ways. Such an exploration might even help speed us along on our own journeys toward understanding those perplexing questions about love that Rabih is trying to answer. As Alain de Botton notes, it will ultimately be Rabih’s ability to see past his cultural conventions that will allow him to live up to his cultural ideals. He suggests that Rabih will need

“…to recognize that the very things that he once considered romantic – wordless intuitions, instantaneous longings, a trust in soul mates – are what stand in the way of learning how to be with someone. He will surmise that love can endure only when one is unfaithful to its beguiling opening ambitions, and that, for his relationships to work, he will need to give up on the feelings that got him into them in the first place. He will need to learn that love is a skill rather than an enthusiasm.”

A WORLD WITHOUT MONEY

Nimakot, Papua New Guinea

Matius had big plans for the day. He would be seeing one of his trading partners from a distant village, and hoped that he could ask him to support him in his quest to pay his bride price. It didn’t bother Matius that his trade partner would be part of a planned attack on his village. In fact, he seemed excited by the prospect.

As word of the pending attack spread, all of the men from the village, along with a few close friends and kin from other villages, came in from their garden houses and hunting excursions, filling the village with a sense of intense anticipation. Men performed chants and dances in the village clearing, pumping themselves up for the attack, while women peeked out through the cracks and darkened doorways of village huts, anxiously awaiting what was to come.

We built a barricade of trees, limbs, and vines along the main path, but we knew this would do little more than slow them down.

Around noon, we heard a twig snap just beyond our barrier, and the village erupted into a frenzy of action. “Woop! Woop! Woop!” we heard the attackers call out, as dozens of them crashed our barricade and came rushing down the mountain into our village. Their faces were painted red and their hands dripped with what looked like blood, but they were not armed with spears or bows. They were armed instead with sweet potatoes dripping with delicious and fatty red marita sauce. They smashed the dripping tubers into our faces, forcing us to eat, attacking us with kindness and generosity.

They left as quickly as they came, but the challenge was set. We were to follow them back to their village and see if we could handle all the food they had prepared for us. We had to navigate a series of booby traps and sneak attacks of generosity along the way, sweet potatoes and taro being thrown at us from the trees. When we finally arrived at the edge of the village, their troops gathered for one last intimidating chant. They circled in and yelled as loudly as they could for as long as they could, letting the giant collective yell drown out in a thumping rhythmic and barrel-chested “Woop! Woop! Woop!” We responded in kind with our own chant, and then charged in for the food.

As we entered the village, we found a giant pit filled with red marita juice filled to the brim with hundreds of sweet potatoes and taro. It was bigger than a kiddie pool, no less than six feet across and nearly two feet deep. The marita seeds that had been washed to create this pool littered every inch of ground throughout the entire village. It was no wonder that the attack had taken several days to prepare.

We settled in for the feast with gusto, dozens of us taking our turn at the pit. But an hour in we were starting to fade, and the waterline of our pool of food seemed barely to budge. Our hosts laughed in triumph and started boasting about how they had gathered too much food for us to handle, giving credit to those among them who cleaned it, processed it, thanking each contributor in turn, and then proudly boasting again that their generosity was too much for us. We left, defeated, but already taking stock of our own marita produce and planning a return attack in the near future.

This is a world without money, banks, or complex insurance policies. Their items of value (like marita and sweet potatoes) cannot be stored indefinitely without spoiling. So large events like this serve a similar function as our banks and insurance companies. When they have a windfall of marita they give it away, knowing that when we have a windfall of marita we will return the favor. Such events strengthen social bonds and trade relationships, which are essential to survival in tough times.

For decades, most economists built their models on rational choice theory – the assumption that all humans are selfish and seek to maximize their own material gain. But these beliefs and values may be a reflection of our own socially constructed realities revolving around money in a market economy, rather than human nature. In these New Guinea villages, they struggle instead to demonstrate their generosity and minimize their material gain. They are not trying to accumulate wealth. Instead, they are trying to nurture relationships through which wealth can flow. This does not mean they are not rational, but when applied in New Guinea, rational choice theory has to account for the different motives and values created within the cultural context of different economic systems.

Anthropologists describe the difference between these economic systems as gift economies and market economies. In both economies, the same items might be exchanged and distributed, but in one they are treated as gifts and in the other they are treated as commodities.

Take, for example, a bag of sweet potatoes. In a gift economy, the bag of sweet potatoes is given with no immediate payment expected or desired. Instead, the giver hopes to strengthen the relationship between themselves and the recipient. The giver will likely give a brief biography of the potatoes, who planted them, tended them, harvested them, and so on, so that the recipient understands their connection to several people who have all contributed to the gift. In a commodity economy, that same bag becomes a commodity. It has a price, something like $5, and the recipient is expected to pay this price immediately. Once the price is paid, the transaction is over.

There are strong practical reasons for gift economies and market economies. Gift economies tend to thrive in small communities and where most things of value have a short shelf-life. Wealth is not easily stored, and there are no banks or currencies for them to store their wealth in either. The best way to “store” wealth is to nurture strong relationships. That way, when your own maritas are not ripe or your garden is out of food, all of those people that you have given to in the past will be there to give to you.

But beyond these practical reasons for the gift economy, are also some profound implications for the core values, ideas, and ideals that emerge in gift economies. In gift economies, people are constantly engaged in relationship-building activities as they give and receive gifts throughout the day. The constant reminders of where the gift came from and all the hands that helped give them a profound sense of interdependence. Along with this sense of interdependence comes a value on relationships rather than things. Most “things” are quickly consumed, rot, and fall apart. It is far more beneficial to have a strong network of relationships than a big pile of slowly rotting sweet potatoes.

It is only in this context that we can begin to understand the practice of “bride price” in New Guinea, and why Matius must face this seemingly impossible task of gathering $3,000 worth of items in exchange for his bride. From the Western perspective grounded in the logic of a market economy, this looks like he is “buying” a wife. But from the logic of a gift economy, he is building and strengthening a vast network of social relationships that will soon unite his network with the network of his bride.

The day turns out to be a great success for Matius. His trading partner has agreed to support him. His gift will join with the gifts of many others. And when Matius gives this bundle of gifts to his bride’s family, they will spread those gifts throughout their network. By the logic of the gift economy, these people will give back, and a large cycle of giving will be created that unites two large networks that intersect at the new node created by the union of the bride and groom.

MARRIAGE WITHOUT LOVE

Maasai Boarding School, Kenya

A similar gift logic operates among the Maasai as well. When Esther’s father arranged for her marriage at age 14, he was following a customary system in which the parents of both the bride and groom agree on the marriage terms for their children while they are still young. The bride price is paid over the course of the entire marriage. “There is probably no greater gift, as viewed by the Maasai, then having been given a daughter,” notes Dr. Achimbault. “Marriage is understood and valued as an alliance of families.”

Esther’s father has three wives and 26 children. This practice of having many wives, known as polygyny, is common among pastoralists like the Maasai. This practice can be especially perplexing to any Westerner who believes in “true love.” In a recent BBC program, a BBC reporter approached some Maasai teenage boys and asks directly, “What does love mean to you?” The boys laugh shyly and one of them rocks back and forth uncomfortably with a broad smile on his face. “That’s a real challenge!” one exclaims and asks his friend to answer, who just giggles and turns away.

The reporter presses on the issue of polygyny. “When you do get married, are you going to take more than one wife or just one?” she asks. One boy answers matter-of-factly, “I will take one or two but no more than two.”

She is taken aback by the nonchalance of his answer. She counters by joking with him, saying if he only takes one he can have her, but she would never be involved in a polygynous marriage. The man starts laughing. “But the work would be very hard for just one wife,” the young man explains. “You would have to look after the cows, goats, water, and firewood – all on your own!”

Recent anthropological studies by Dr. Monique Borgerhoff Mulder support the man’s argument and show that polygynous households among the Maasai have better access to food and healthier children.

One of the Maasai women wants to show the reporter that polygamy is actually good for them, and takes her to see the most senior wife of a polygynous family. She lives in a beautiful brick home, far superior to most of the other homes in the region. The economic incentive for polygyny seems clear, but the reporter is still skeptical about the quality of the marriage relationships. “Don’t you get jealous of the other wives?” the reporter asks.

“No, no. Never.”

“Do you argue?”

“No … we’re friends. We never fight. We are all the same age. We tell stories. We have fun.”

Marriage practices like this are especially mystifying for people in the West. For many Westerners, love is our biggest concern and our strongest value, so when we find cultures that practice arranged marriage or polygamy, we find it strange and immediately infer that there may be a violation of basic human rights. But if we look at all humans through all time, it is our ideas about love that are strange.

Over 80 percent of all cultures worldwide practice polygyny (one man married to more than one woman) and a handful of others practice polyandry (one woman married to more than one man). As hinted at by the response from the Maasai teen that the work of a household would be very difficult for just one woman, the common reasons given for why these forms of marriage often come down to practicality. There is no mention of love.

Such marriages often make sense within the culture and environment. For example, in Tibet, where arable land is scarce and passed down through males, several brothers may marry one woman in order to keep the land together. As anthropologist Melvyn Goldstein has pointed out, if the land were divided among all sons in each generation, it would only take a few generations for the land to be too small to provide enough for the families.

Despite these apparent practical benefits, the value and romanticism we place on love makes the idea of young girls like Esther being married off at a young age unpalatable to most Westerners. When Esther’s father attempts to remove her from school and arrange her marriage, he seems to be upholding oppressive patriarchal values.

But Esther’s father is practical and he wants what is best for his children. He has sent most of his kids to school in hopes that they can find new ways to make a living. However, school is far away and expensive. Due to the dangers and difficulties of getting to school, most girls enter school late, just as they are reaching reproductive age. This creates a risk of early pregnancy, which will get them kicked out of school and greatly limit their marriage prospects. Furthermore, the schools have high drop-out rates and even those who finish are not guaranteed a job.

Pastoralism – the traditional way of making a living – has become more difficult due to frequent droughts brought about by climate change. Land privatization poses an additional problem, since a pastoralist is now constricted to the land to which he has a legal right. In times of drought and scarcity, movement across vast land areas is essential. One strategy for increasing the land one has access to is to create alliances between lineages through strategically arranged marriages. When Esther’s father tried to pull her out of school, he did so because he saw an opportunity for her to have a secure future as a pastoralist with access to good land.

After laying out these essential pieces of context, Archambault makes the case that we should be skeptical of simple “binaries” that frame one side as “modern” and empowering of females and the other as “traditional” and upholding the patriarchy. Such binaries are common among NGOs promoting their plan to improve human rights. But through the lens of anthropology, we can see our assumptions, see the big picture, and see the details that allow us to understand the cultural situation, empathize with the people involved, and ultimately make more informed policy decisions.

LOVE WITHOUT MARRIAGE

Madurai Village, Tamil Nadu, South India

Sunil’s marriage prospects looked good. In an arranged marriage among the Tamil, families carefully consider the wealth, status, reputation, and earning potential of potential marriage partners. Sunil had it all, and he was on his way to earning a prestigious law degree. But then he was struck by katal – an overwhelming sense of intense and dumbfounded longing for another person that we might call “love” in English. They say it is a “great feeling” that can “drive you crazy” and compels you to “do things you would not ordinarily do.” It is a “permanent intoxication,” as one 18-year old Tamil put it.

Love like this is known all over the world. Anthropologist Helen Fisher looked at 166 cultures, and found evidence of passionate love in 147 of them. As for the rest, she suspects that the ethnographers just did not pay attention to it. The Tamil are no different. The feeling of love may not be the foundation for their arranged marriages, but that does not mean the Tamil do not feel love.

Sunil described the girl as “smart, free, funny, and popular.” He met up with her every day after class, and soon he was, as he says, “addicted” to her. Addiction might be the right word. Fisher studied brain scans of people in love and found that the caudate nucleus and ventral tegmental area of the brains lit up each time they were shown an image of their lover. These are areas of the brain associated with rewards, pleasure, and focused attention. Other studies have found that falling in love floods our brain with chemicals associated with the reward circuit, fueling two apparently opposite but mutually sustaining emotions: passion and anxiety. Overall, the studies reveal a chemical profile similar to someone with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

When two people share these feelings together, they can experience a shared euphoria like almost no other experience available to humankind. But when only one person feels this obsessive-compulsive form of passionate love – or when one person stops feeling it while the other still feels it – it can unleash a devastating psychological breakdown.

Sunil’s romance was rocky. They started disagreeing and using harsh words with one another. After a fight one night, Sunil worried that she would leave him. His obsession gripped him with a flood of anxiety. He tried calling her at 2 am, but she did not answer. Desperate to talk to her, he went to her college early the next morning in hopes of catching her before her first class. “She was so happy to see me in the pathetic state I was in,” Sunil lamented. When she called later to break off the relationship, Sunil completely broke down. He became an alcoholic and had to drop out of law school.

After two years of pain and trouble, he finally got over her, stopped drinking, and finished law school. But by then he had already missed out on his best opportunity for a successful arranged marriage with his favorite cousin. The perfect match, someone he had thought about marrying since the time he was a teenager, had come of age while he was drinking away his sorrows and had already married someone else (a different cousin).

Sunil’s story represents an interesting tension at work as Tamil society continues to change. A more urban and mobile society creates more opportunities for young people to meet strangers and to feel katal for them. Education and career opportunities take young people far from home and family. The culture is starting to value individualism, free choice, and autonomy – all of which come together to make love marriages seem attractive. A common theme of Indian movies and television shows is the tension between love and arranged marriages.

However, most Tamil do not elope and create love marriages. From the standpoint of the family, the reasons are clear. As anthropologist Clark-Decés points out, “The basic explanation for this is that marriage is too important to be left to chance individual attraction – in fact, a child’s marriage is the most important and often the most expensive decision a South Asian family ever has to make.”

Worldwide, arranged marriages are especially common when a significant transfer of wealth is at stake, such as a large inheritance, bride price, or dowry. In India, marriage usually entails very large gifts between the families, often the equivalent of three years of salary or more. When the wealth of an entire extended family is on the line, everybody in the extended family has a vested interest in the union and arranged marriages are the norm and ideal.

It is not surprising then that the parents of bride and groom would prefer an arranged marriage. However, Clark- Decés and other anthropologists note that arranged marriage remains the norm and ideal among youth as well. Young men like Sunil want to achieve success and respectability within the ideals and values of their culture. They view marriage as the union of two families, not just two people. And ultimately, “for them, an arranged marriage is a sign of parental love.”

This preference for arranged marriages has a profound impact on how people grow up. As Clark-Decés points out, the social category of “bachelor” is non-existent. Tamil youth do not spend a great deal of time in their teens and twenties worrying about who to date or how to date, since that is rarely the road toward marriage. Instead, they focus primarily on attaining significant status markers that confer wealth and prestige, such as their education. Whereas college in the United States is often seen as a place to meet a potential mate, college in South India is a place where one earns a degree to elevate their status for an arranged marriage.

It is not that love is absent or impossible in arranged marriages, but it is not the primary basis upon which marriages are formed. In a recent survey, 76% of Indians said they would marry someone if they had the right qualities, even if they were not in love. Only 14% of Americans would do so. As Leena Abraham found in a study of college students in Mumbai, love marriages are “seen as an arrangement beset with enormous insecurity.”

ORIGINS OF LOVE MARRIAGE

Love marriage was once uncommon in the West as well. It was not until the Industrial Revolution and the broad cultural changes that came with it that love marriage became the norm. With the Industrial Revolution, individuals were no longer tied to land held in the family name. They became more mobile and less dependent on family and community for survival. People started orienting their lives more toward the market, and they could use the state for a safety net, weakening their dependency on relationships and family.

This increased individualism had two competing effects. On the one hand, it gave people more freedom. They became accustomed to making individual choices every moment of the day. But this freedom came with a cost. As they had more and more choices about what to buy, what to do, and how to act, they were also increasingly troubled with the question of whether or not they were choosing the right thing to buy, the right thing to do, or the right way to act. They came to suffer from a sense of what Emile Durkheim called anomie, a condition in which society provides little guidance and leaves people feeling lost and disconnected.

Feeling empowered by the power to choose, yet feeling lost and disconnected, romantic love marriage emerged as the perfect solution. We go searching for “the One” who can make us “feel whole” and “completes us.” This is the key to understanding just how different we are from those Massai teens. They live in small, close-knit communities full of tight bonds to family and friends. Large, close-knit families are still the ideal in India as well. They do not need more intimacy. They have enough of it already. We, on the other hand, often feel alone, lost, and insecure. We crave intimacy. We crave a sense of validation. And we find that through love.

Unfortunately, this sets up an impossible situation. With the breakdown of family and community, we often turn to our lovers for intimacy, friendship, and economic support. One person is expected to provide all of this and passion at the same time. “We now ask our lovers for the emotional connection and sense of belonging that my grandmother could get from a whole village,” notes family therapist Sue Johnson. But the security necessary for the intimacy and friendship we crave along with the everyday trials and mundanity of running a household can kill passion.

THE PARADOXES OF LOVE AND MARRIAGE

Edinburgh, Scotland

“For most of recorded history, people married for logical sorts of reasons: because her parcel of land adjoined yours, his family had a flourishing grain business, her father was the magistrate in town, there was a castle to keep up, or both sets of parents subscribed to the same interpretation of a holy text … what has replaced it – the marriage of feeling … What matters is that two people wish desperately that it happen, are drawn to another by an overwhelming instinct, and know in their hearts that it is right.”

- Allain de Botton

In his book The Course of Love, philosopher Allain de Botton tells the love story of Rabih and Kirsten, along with his cutting observations about love and marriage. After a whirlwind romance, Rabih proposes to her, hoping to capture the feelings he and Kirsten have for each other and preserve them forever. Unfortunately, you cannot freeze a feeling, or marry one. You have to marry a person with whom you once shared a feeling. And feelings are not necessarily forever.

In A Natural History of Love, anthropologist Helen Fisher identifies two kinds of love: the burning fire of romantic passionate love, and the enduring intimacy and calm of companionate love. These two loves have very different chemical profiles in the brain. Romantic love is a rush of dopamine, a drop in serotonin, and a rise in cortisol that creates an intense passion and desire. Companionate love activates the attachment circuits of the brain. It is oxytocin-rich and induces a loving calm and sense of security. Unfortunately, this sense of calm and security can actually work against our feelings of passion. Passion thrives on insecurity. The reason for our obsessive ruminations and fluttering hearts is in part the very frightening idea that we might lose this person or that they might not return our love. The more we try to freeze the feeling by “locking in” the relationship through promises, proposals, or other means of entanglement, the more we drive it away. A desire for connection requires a sense of separation. The more we fuse our lives together, the less passionate we become.

This is not a problem in many cultures where passion in marriage is not required or expected. But in the West, there is a strong sense that “true love” burns with passion forever. If passion fades, it isn’t “true love.”

So as Rabih and Kirsten squabble in Ikea over which drinking glasses to purchase for their apartment, there is a lot more at stake than mere aesthetics. This will be one of thousands of little squabbles that are unavoidable when merging two lives, but they will always reflect deeper concerns and misgivings each one has about the other person. Such squabbles will be the main forum where they will try to shape and shift one another, make adaptations and compromises in who they are, and assess the quality of their relationship.

These negotiations are fraught with tension because of another ideal of “true love”—that it is unconditional, and that if someone truly loves you they will unequivocally accept you for all that you are and never try to change you. Each little push or prod feels like a rejection of the self.

Behind these feelings are deep and profound cultural assumptions about love itself. We tend to focus on love as a feeling. But according to a landmark book by psychologist Erich Fromm, our focus should not be on “being loved” so much as it should be on the act of loving and building up one’s capacity to love. This insight runs counter to the cultural ideal of “true love” which says that when we find the right person, love will come easily and without effort. As a result of our misunderstandings about love, Fromm argues, “there is hardly any activity, any enterprise, which is started with such tremendous hopes and expectations, and yet, which fails so regularly, as love.”

This basic insight is easy to accept intellectually, but it is quite another thing to incorporate it into your everyday life. For Rabih and Kirsten, it is the arrival of their first child that helps them understand love as something to give rather than something to merely feel and expect to be given. The helpless and demanding baby gives them ample practice in selfless love of another without any expectation of return.

Unfortunately for Rabih and Kirsten, their ability to love their child does not translate into an act of loving for one another. In the midst of sleepless nights, diaper changes, and domestic duties, there is little love left to give after caring for the baby. Over the coming years, Rabih and Kirsten admire each other greatly for the patience and care shown for their children, but also feel pangs of remorse and jealousy that such love and kindness had become so rare between them.

One would think that after so many years of marriage, people would stop needing a sense of validation from the other. But, de Botton notes, “we are never through with the requirement for acceptance. This isn’t a curse limited to the inadequate and the weak.” So long as we continue to care about the other person, we are unlikely to be able to free ourselves from concerns about how they feel about us.

Unfortunately, Rabih and Kirsten need very different things to feel a sense of validation. Rabih wants to rekindle the passionate love they once shared in sexual union. But after a long day of giving her body and self to her children, Kirsten does not want to be touched. She needs time to herself, and Rabih’s “romantic” proposals feel like just another thing to put on her long “to do” list for others.

Allain de Botton’s Story of Love recounts many twists and turns in the love story of Rabih and Kirsten. It is an honest portrayal of a true love story in which seemingly mundane arguments about who does more housework take their rightful place alongside more dramatic affairs and bouts of jealousy. Though they often feel distance between them, they go through everything – raising kids, watching their own parents grow old and die – together.

It is only after all of this – 13 years after saying their vows – that Rabih finally feels “ready for marriage.” He is ready not because he is finally secure in an unequivocal faith in a perfect love with his soul mate for whom he feels an unbounding and never-ending sense of passion, but because he has given up on the idea that love should come easily. He is committed to the art of loving, not just a desire to be loved, and looks forward to all that his life, his wife, and his children might teach him along the way.

LEARN MORE

“Ethnographic Empathy and the Social Context of Rights: ‘Rescuing’ Maasai Girls from Early marriage” by Caroline S. Archambault. American Anthropologist 113(4):632-643.

The Right Spouse: Preferential Marriages in Tamil Nadu, by Isabelle Clark- Decés

The Course of Love: A Novel, by Alain de Botton

Becoming Our Selves

Daniel has no eyes. Born with an aggressive eye cancer, they were removed before his first birthday. From an early age, Daniel realized that he could sense what objects are around him and where they are by clicking and listening for the echoes. Ever since then, like a bat, he uses echolocation to find his way around the world. It has allowed him to run around his neighborhood freely, climb trees, hike alone into the wilderness, and generally get around well as someone with perfect vision. “I can honestly say that I do not feel blind,” he says.

In fact, he never thought of himself as “blind” until he met another boy named Adam at his elementary school. By then, Daniel was already riding bikes, packing his own lunch, and walking to school by himself. Adam, in contrast, had always attended a special school for the blind and had a constant supply of helpers to escort him through the world and guide him through his daily routines.

Daniel was frustrated with Adam’s helplessness. He couldn’t understand why Adam couldn’t do things for himself or join in games on the playground. Even worse, the other kids started to mix Daniel and Adam up. They were “the blind boys.” For the first time, Daniel felt what it was like to have society define him as “blind.” And he was shocked and frustrated to discover that society did not expect any more from him than they did from Adam.

He had trouble making sense of it until he found a book by sociologist Robert Scott called The Making of Blind Men. In that book, Scott suggests that blindness is socially constructed. From the first powerful paragraph onward, Scott argues that “the various attitudes and patterns of behavior that characterize people who are blind are not inherent in the condition but, rather, are acquired through ordinary process of social learning.”

To most people, this sounds shocking and farfetched. How can blindness be “socially constructed”? Blindness seems to be a matter-of-fact physical reality, especially in the case of Daniel, who has no eyes. But Scott doesn’t mean to question this physical reality. Instead, he wants to challenge the assumptions that create a social role for blind people as “docile, dependent, melancholy, and helpless.” Throughout his research, he meets many people like Daniel who defy these expectations, but finds others who have been conditioned to fit the stereotype. “Blind men are made,” Scott declares emphatically, “by the same process of socialization that have made us all.”

Scott moves the discussion beyond blindness to point out that we are all “made.” Our self-concept is our estimation of how others see us given our culture’s core beliefs, expectations, and values. This self-concept in turn shapes how we perceive the world and engage with it. In other words, most of what we take as “reality” is socially constructed, “real-ized” through our unseen, unexamined assumptions about what is right, true, or possible.

Scott reveals three processes through which our realities – such as “blindness” – are real-ized.

- Beliefs and expectations: The first is the process of enculturation through which we learn the basic “common sense” beliefs and values of our culture. From an early age, people learn a set of stereotypical expectations and beliefs about blind people as “docile, dependent, melancholy, and helpless.” Blind people take on these beliefs and expectations as part of their self-concept.

- Behaviors and interactions: Second, these beliefs become guidelines for our behaviors and interactions with others. In this way, even if a blind person has the fortitude to reject the stereotypes of blindness put upon them, they might be denied opportunities for more independence by the expectations of others who do not allow the blind person to take on a job or do other things for themselves.

- Structures and institutions: Third, these beliefs and behaviors are woven into larger institutions and other social structures through which the beliefs and behaviors are reinforced. Institutionalized norms, laws, behaviors, and services shape our beliefs about what is right, true, and possible.

Scott found that blind people were encouraged to attend special schools and follow specific job tracks designed to accommodate their disabilities. They were offered free rides, escorted by hand through their daily activities, and had many of their daily tasks done for them. While these are all well-intentioned services, Scott also noticed that they reinforced the message that “blind people can’t do these things.” When Scott did the original research for his book in the 1960s, nearly 2/3 of blind American students were not participating in gym class. He worried that by treating blind people as helpless, they were becoming more helpless.

Many studies support this concern. Even rats seem to change their behavior based on what people think of them. In a remarkably clever experiment, psychologist Bob Rosenthal lied to his research assistants and told them that one group of rats was “smart” and another group “dumb.” They were, in fact, the same kind of rats with no differences between them, yet the “smart” rats performed twice as well on the experimental tests as the “dumb” rats. Careful analysis found that the expectations of the experimenters subtly changed the way they behaved toward the rats, and those subtle behaviors made a big difference.

Other studies have found that teacher’s expectations of students can raise or lower IQ scores and a study of military trainers found that their expectations can affect how fast a soldier can run. As psychologist Carol Dweck explains, we convey our expectations through very subtle cues, such as how far we stand apart and how much eye contact we make. These subtle behaviors make a difference in how people perform.

While we all understand the power of our own belief on our own behavior, these studies demonstrate that other people’s beliefs can also affect us. This link between belief and behavior can become a vicious circle. A teacher’s low expectations make a student perform poorly. The poor performance justifies and re-enforces the low expectations, so the student continues to perform poorly, and so on.

Daniel Kish was raised by a mother who refused to let society’s expectations of blindness become Daniel’s destiny. She let him roam free and challenged him to find his own way to make his way in the world. As a result, Daniel’s mastery of echolocation allowed him to “see” and distinguish trees, park benches, and poles. He now enjoys hiking in the woods, bike rides, and walking around town without any assistance or seeing aids.

These abilities are reflected in his brain. Brain scans show that Daniel’s visual cortex lights up as he uses echolocation. His mind is actually creating visual imagery from the information he receives through echolocation, so despite not having any eyes, he can see. Recent studies suggest that he actually sees with the same visual acuity as an ordinary person sees in their peripheral vision. In other words, he may not be able to read the words in a book, but he knows the book is there.

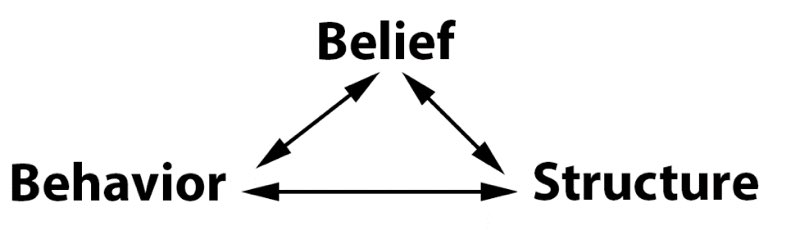

The story of Daniel Kish is a fitting opening for this lesson, because it reveals how a trio of forces – beliefs, behaviors, and structures – can shape how we see the world and ourselves. From an early age we are immersed in beliefs, behaviors and structures that tell us how to be a man or a woman, what it means to be “white,” “black,” or “Asian,” and what qualifies as “handsome,” “beautiful,” or “sexy” among many other ideals and values that will form the backdrop against which we will form our sense of who we are.

GENDER: BIOLOGY OR CULTURE?

In the toy section of a store, you are likely to find an aisle of soft “girly” colors like pink and purple populated with dolls and playhouses. The next aisle has colder colors and sharper edges with guns and cars. Before they can put together a full sentence, most children will know which toys are for boys and which are for girls. Do these different interests of boys and girls reflect innate biological differences, or is the socialization of boys and girls so powerful that it already starts to appear at a very young age?

An issue of Ladies Home Journal in 1918 assigned blue to girls and pink to boys. It wasn’t until the 1940s that American culture settled into the now familiar and taken-for-granted idea that pink is for girls and blue is for boys. But while the color of the toys is obviously a cultural construction, the boy’s affinity for cars and trucks and the girl’s affinity for dolls continues to be the subject of wide-spread debate in neuroscience, biology, psychology, and the social sciences.

In 1911, Thorndike suggested that the reason boys like trucks and girls like dolls is that men are more interested in “things and their mechanisms” and women are more interested in “persons and their feelings.” Though highly controversial, a meta-study by Su, Rounds, and Armstrong in 2009 that analyzed dozens of studies on the topic found that men and women across multiple cultures see themselves differently, as “Women reported themselves to be higher in Neuroticism, Agreeableness, Warmth, and Openness to Feelings, whereas men were higher in Assertiveness and Openness to Ideas.”

The differences were modest but statistically significant, and they seemed to confirm gender stereotypes. Other studies reveal similar results. Though there is no total scientific consensus, there is a strong contingent of scientists concluding that there are small but significant differences between men and women in their personality traits and interests. Conforming to the expectations of gender stereotypes, on average, women are slightly better than men when it comes to verbal reasoning, feeling, and empathy, while men on average are slightly better at systems thinking and spatial visualization. On average, women are more agreeable while men are more aggressive and assertive. The largest difference is that on average, women are more interested in people while men are more interested in things.

These differences are subtle, and there is a lot of overlap between men and women. If you were to pick a man or woman at random and try to guess if they would be above average in any of these traits, you would only improve your odds very little if you went with the stereotype. But even a small difference can matter a great deal when looking at what roles and careers people choose to pursue; indeed, a small difference in an average can make a big difference at the extremes. These subtle differences might potentially explain why women are so vastly under-represented in STEM fields but make up the majority of nurses and clinical psychologists (due to an interest in people vs. things). They might also explain why women are less well-represented in leadership positions (due, potentially, to men being more aggressive and less agreeable).

Are these differences real and permanent? Are they biological or cultural? The stakes of this debate are high. If these gender differences are real, innate, and unchangeable, then there may be little reason to suspect wide-spread discrimination and bias as the reason behind gender inequality. It might instead be a product of gendered choices and inclinations. Proponents of this position argue that we already have equal opportunity laws in place and a culture that promotes and champions the freedom to pursue your dreams. They suggest that perhaps the gender gap and apparent inequality is just a product of individual choices.

There are high stakes for men as well. Gender stereotypes that propose that men are more violent, courageous, and strong-willed, along with gender roles that ask men to provide for the family, serve the country, and sacrifice themselves for others while showing no signs of emotion or weakness, lead to many negative outcomes for men. While it is easy to look at the fact that 80% of all political leadership positions and 93% of the Fortune 500 CEOs are men and think that men have all the privilege, we should also consider the effect of gender stereotypes on the vast majority of men. Men’s Rights Activists point out that men make up 97% of combat fatalities. They do more dangerous work, making up 93% of all work fatalities. Because they are stereotyped to be less nurturing, they lose custody in 84% of divorces. They also struggle more in school, making up just 43% of college enrollments. The problems start early, as they are nearly twice as likely as girls to repeat kindergarten.

With such high stakes, a constant flurry of articles, blog posts, YouTube videos, and message boards create a highly contentious and polarized cultural space where the origin and value of stereotypes is vehemently argued.

Contrary to what we would expect if these differences were biological and innate, they differ in magnitude across cultures. However, contrary to what we might expect if the differences were cultural, they are more pronounced in cultures where sex roles are more egalitarian and minimized, such as in European and American cultures. In Northern Europe, where gender equality is highest, gender differences in career choice are the most pronounced. Proponents of the biological thesis suggest that this is definitive proof that these differences are innate and not socially constructed.

But there are many critics of these studies. They point out a number of flaws in the studies that replicate gender stereotypes while offering little evidence that the stereotypes are actually true. For example, many of the most-cited studies ask participants to self-report on their level of empathy or respond hypothetically to prompts such as “I really enjoy caring for people” or “When I read the newspaper, I am drawn to tables of information, such as football league scores or stock market indices.” Critics have found that in research situations in which people are reminded of their gender and gender stereotypes, the differences are magnified, but in situations where their gender is minimized the differences go away. A careful review of these studies by scholars like Cordelia Fine have found these self-report studies are unreliable in predicting actual behavior or actual ability, and the content of the questions themselves signal gender stereotypes (men like football and stock markets) that reveal little about how men and women actually think and more about how they have been culturally conditioned.

In short, the studies that attempt to suggest that gender differences are entirely rooted in biology continually come up short, but that is not to say there are not real biological differences. As biologists Anne Fausto-Sterling has summarized the situation, the brain “remains a vast unknown, a perfect medium on which to project, even unwittingly, assumptions about gender.” But despite these unwitting assumptions, the cutting-edge research in psychology and neuroscience have demonstrated that there are real sex differences in the brain that should not be overlooked. Ongoing research is focusing less on whether gender is strictly biological or strictly cultural, and instead how biology and culture intersect in the creation of gender, trying to understand gender as a biocultural creation.

ARE GENDER STEREOTYPES UNIVERSAL?

Gender roles and stereotypes are pervasive in all cultures, and while there is some variation, there is also considerable overlap. All over the world and across almost all cultures, men hold more positions of leadership in economic, political, and religious domains, while women are most often the primary caregivers. Throughout much of human history, women would have been the primary source of sustenance for growing babies through breast feeding, leaving it to the man to do more work outside the home to bring home food. Men tend to be associated with public activities, while women are more associated with domestic activities. These differences usually also entail differences in status and power, so that globally we see pervasive inequality between men and women.

In Nimakot, Papua New Guinea, traditional religious beliefs practiced until the 1980s were centered around the great ancestress Afek. Temples throughout the region marked key places where she literally “gave birth” to the key elements of the culture. Women’s reproductive powers were highly revered and feared. Menstrual blood was seen as dangerous and polluting. During their periods, women were required to stay in a small menstrual hut away from the main village, and women were never allowed into the men’s house, where the most sacred rituals surrounding the ancestress took place. So while it may appear that women are given a lofty status in light of the culture revolving around an ancestress, in practice women were locked out of positions of sacred and political power, and forced into confinement for three days of every month.

There are a wide range of approaches and opinions on these matters, even within the same culture or religion. Some Muslim women, for example, see the wearing of the hijab head-covering as oppressive, refuse to wear it, and encourage other women to give it up as well. But other Muslim women argue that it is their right and choice to wear the hijab as an expression of their submission to God, and that it gives them the freedom to move about in public without the leering and objectifying eyes of men. Some of these same Muslim women argue that it is the scantily-clad Instagram model obsessed with her looks, morphing her body through diets, postures, and surgery, who is truly overcome and controlled by the gaze of men.

There is also considerable cultural variation in the total number of genders. The socialization of “men” and “women” starts at a very young age. By the time we are making the wish-list for our fifth birthday, we already take it for granted that there are two distinct categories of children: boys and girls. But a quick review of gender roles and categories around the world demonstrates that many of our ideas about gender are socially constructed and can exist in very different ways in different cultures.

It is commonly assumed that one is just born male or female, and while it is true that there are important biological differences formed at birth and ongoing differences that emerge throughout life, these are not easily put into a simple binary of male and female.

To understand this complexity, anthropologists find it useful to distinguish between sex and gender. Sex refers to an individual’s biological traits while gender refers to cultural categories, roles, values, and identities. In short, sex is biological. Gender is cultural.

In India there is a third gender called the Hijra. Hijra are people who were usually born male but live their lives as a third gender, neither male nor female. Some are born intersexed, having both male and female reproductive organs. Texts dating back 4,000 years describe how Hijra were thought to bring luck and fertility. Several Native American cultures have also traditionally recognized a third gender and sometimes ascribed special curing powers to them. The Bugis on the island of Sulawesi recognize five genders. What we call “transgendered men” or “transgendered women” have a ready and identifiable role and place in their society. To these they add a fifth, the Bissu. Bissu are androgynous shamans. They are not merely thought to be gender neutral or non-binary. A better translation is that they are “gender transcendent.” They are thought to have special connections to the hidden world of “batin.” The Bugis believe that all five genders must live in harmony.

These more complex systems that move beyond the simple binary of male and female may be better suited for the realities of human variation. Over 70 million people worldwide are born intersexed. They have chromosomes, reproductive organs, or genitalia that are not exclusively male or female. In societies where such variations are not accepted, these individuals are often put through painful gender assignment surgeries that can cause psychological troubles later on if their inner identity fails to match with the identity others ascribe to them based on their biology.

“MAKING GENDER”

To understand how gender might be socially constructed, we can remove the references to blindness from the example in the opening story and create a sort of “Mad Libs” for the social real-ization of gender. You could fill in the blanks below with the expectations associated with either gender to create a short summary of how that gender is socially constructed.

- Beliefs and expectations: From an early age, people learn a set of stereotypical expectations and beliefs about men/women as “__________.” Men/women take on these beliefs and expectations as part of their self-concept.

- Behaviors and interactions: Second, these beliefs become guidelines for our behaviors and interactions with others. In this way, even if a man/woman has the fortitude to reject the stereotypes put upon them, they might be denied opportunities for ____________ by the expectations of others who do not allow the men/women to ________.

- Structures and institutions: Third, these beliefs and behaviors are woven into larger institutions and other social structures through which the beliefs and behaviors are reinforced. Institutionalized norms, laws, behaviors, and services shape our beliefs about what is right, true, and possible.

Together, these three concepts make up a trio of real-ization, with each element relating to and re-enforcing the others. You could draw the relations between them like this:

In a landmark set of essays called “Making Gender,” anthropologist Sherri Ortner explores the relationships between these domains as a way of exploring how gender roles, stereotypes, and relationships might change or get reproduced in our everyday actions. She notes that this involves “looking at and listening to real people doing real things … and trying to figure out how what they are doing or have done will or will not reconfigure the world they live in.” For her, the anthropological project consists of understanding the cultural constraints of the world, as well as the ways in which people actively live among such constraints, sometimes recreating those same constraints, but sometimes changing them.

Consider the first element: beliefs and expectations. Cordelia Fine asks you to imagine that you are part of a study in which the researcher has asked you to write down what males and females are like according to cultural lore. You might resist the idea that people can be stereotyped, but you would have no trouble reproducing the stereotype. “One list would probably feature communal personality traits like compassionate, loves children, dependent, interpersonally sensitive, nurturing … On the other character inventory we would see agentic descriptions like leader, aggressive, ambitious, analytical, competitive, dominant, independent, and individualistic.” She concludes by noting that you would have no trouble knowing which one matches which gender.

Unfortunately, even if you don’t buy into these stereotypes, you can’t help but take them into account in forming your own self-concept. They are part of the cultural framework and meaning system upon which we craft our identity and sense of self. Even if we explicitly choose to craft an identity against these stereotypes, we do so in full acknowledgment that we are doing so, and that we may need to be prepared for how the world might receive us. A woman who demonstrates an aggressive leadership style will likely be perceived more negatively than a man with the same approach, while a stay-at-home dad who shows emotion easily may be openly ridiculed for not properly providing for his family. In short, we do not craft our identities in a social vacuum and must account for cultural stereotypes as we navigate the world.

In this way, beliefs and expectations shape the second element; behaviors and interactions. We have probably all experienced ourselves bending our personalities ever so slightly to accommodate a particular situation. If we are around people we think might hold stronger traditional gender stereotypes, we are likely to change our behavior to match their expectations. Controlled studies by Stacy Sinclair in which women are told that they are about to meet with a charming but sexist man led these women to self-assess themselves as more stereotypically feminine.

Other studies prime students with gender stereotypes and then give them moral dilemmas to see how they will respond. For example, in a study by psychologist Michelle Ryan, one group of participants was asked to brainstorm ideas for debating gender stereotypes and another was not. Then they were asked to solve a moral dilemma. Among those who had brainstormed the ideas for debating gender stereotypes, women were twice as likely to respond to the moral dilemma by offering empathy and care-based solutions in line with gender stereotypes.

In other words, whenever the gender stereotype is in mind, people shape their behavior in relation to that stereotype. It is surprisingly easy to bring the stereotype to mind. When researchers at American University added a small checkbox to indicate your gender as male or female to the top of a self-assessment, women started rating their verbal abilities higher and math abilities lower than when the checkbox was not on the form.

Psychologists who study “stereotype threat” call this “priming.” It is a technique used in the lab to “prime” research participants with a gender stereotype, role, or identity before doing another task to see how it effects the outcome. But these effects go far beyond the lab, because while the “priming” done in the lab is often very subtle, we live our lives completely immersed in situations that can prime these gender stereotypes. As evidence of this, consider the constant barrage of advertisements we see online, on TV, and in our social media feeds that reproduce gender stereotypes and consider their effect. When researcher Paul Davies showed research participants advertisements of women in beauty commercials or doting over a brownie mix and then asked them to take an exam, he found that women attempted far fewer math problems than they did if they were shown more neutral ads. They also were less likely to aspire to careers in STEM fields after seeing these commercials. Psychologists Jennifer Steele and Nalini Ambady conclude that “our culture creates a situation of repeated priming of stereotypes and their related identities, which eventually help to define a person’s long-term attitude towards specific domains.”

As a result of the stereotypes and behaviors they influence, we end up creating the third element: structures and institutions. Women who resist the stereotype and pursue STEM fields, attempt to climb corporate ladders, or pursue political success will find fewer and fewer other women alongside them as they move up the ranks. They find themselves in male-dominated institutions that reinforce and reproduce the stereotypes. Despite the progress made over the past 50 years, they may still face discrimination in hiring and promotion, or they may find that their ideas or opinions are not often accepted, or they may find themselves immersed in a masculine culture where they find it difficult to fit in and be effective.

Meanwhile, in Armenia, women make up about half of computer science majors (vs. 15% in America). Hasmik Gharibyan suggests that this is because Armenians do not expect to have a job they love. Jobs are for financial stability. Joy is to be found in family and friends, not a job. We see a similar pattern in other developing countries, so that contrary to many expectations, those countries with more traditional views of gender have less gender inequality.

As mentioned earlier, many of those who favor a biological explanation take this as evidence that men and women have innately different interests and abilities leading them down different career paths when they have total freedom of movement. However, sociologists Maria Charles and Karen Bradley argue that these differences result from our strong cultural emphasis on individual self-expression. Unlike developing countries, self-expression plays a large role in career choice over practical considerations. Being an anthropology major or an engineering major is as much an identity as it is a career.

In this way, a culture that values self-expression may exaggerate and exacerbate the stereotypes and frameworks that provide the raw material from which people construct their selves. While the impact of stereotypes may seem small in any particular situation, we are never not in a situation, and these effects add up and result in substantially different and gendered behavioral patterns, interests, and worldviews. These behaviors, interests, and worldviews then become a part of the social world that others must navigate, thereby perpetuating the stereotypes.

We do not know yet how this social construction interacts with biological processes in the brain, but as anthropologists, sociologists, psychologists, biologists, and neuroscientists continue their explorations into how gender is made, we will likely see many important new discoveries in the field demonstrating the complexities of this biocultural creation.

RACE AS A BIOCULTURAL CONSTRUCTION

Most Americans publicly proclaim that they are not racist, but all Americans know the common stereotypes and how they map on to each racial category. The idea that there are “blacks” “whites” and “Asians” goes largely unquestioned. But many anthropologists propose that when we look at the entire global human population, the notion of race is a myth. It is a cultural construction. As biological anthropologist Alan Goodman notes, “what’s black in the United States is not what’s black in Brazil or what’s black in South Africa. What was black in 1940 is different from what is black in 2000.” Scientists like Goodman note that if you lined up all the people on the planet in terms of skin color you would see a slow gradation from light skin to dark skin and at no point could you realistically declare the point at which you transition from “black people” to “white people.”

How did our skins get their color? Skin color is an adaptation to sun exposure. Populations in very sunny areas along the equator have evolved to produce more melanin, which darkens the skin and protects them from skin disorders as well as neural tube defects that can kill unborn children. Populations in less sunny areas have evolved with less melanin so that their lighter skins can absorb more Vitamin D, which aids in the absorption of calcium, building stronger bones.

When anthropologists argue that race is a myth, they are pointing out that variations in skin color cannot be neatly categorized with other traits so that people can be clearly separated into clear types (races) along the lines created by our cultural concept of race. For example, some populations in the world that have dark skin have curly hair, while others have straight hair. Some are very tall, and some are very short. Humans have a tendency to create categories based on visual traits like skin color because they’re so prominently visible. But, as anthropologist Marvin Harris notes, organizing people into racial types according to skin color makes as much sense as trying to organize them according to whether or not they can roll their tongues. Skin color, like tongue-rolling, is highly unlikely to correlate with any complex behavior such as intelligence, discipline, aggression, or personality, in part because these complex behaviors are strongly shaped by culture and therefore the racial categories and stereotypes in any given culture will have a profound effect on those behaviors.

This is not to say there is not significant human variation across populations, but cutting-edge DNA studies from revolutionary studies in genetics have shown that the boundaries of what might be considered “populations” have always been changing. As geneticist David Reich points out, there were different populations in the past, but “the fault lines across populations were almost unrecognizably different from today.” So while different populations differ in bodily dimensions, lactose tolerance, disease resistance, and the ability to breath at high altitudes, these differences do not fall into neat, fixed, unchanging, and scientifically verifiable racial categories.

Currently, most anthropologists maintain that race is a social construction with no basis in biology. However, some anthropologists are now arguing that our social constructions are having a real impact on biology. For example, if someone is socially classified as “black,” they are more likely to live in conditions with limited access to good nutrition and healthcare. In short, as Nancy Krieger recently noted, “racism harms health,” and this means that different races have different biology, but this biology is in part shaped by social forces.

At the root of these health inequalities is continued racial segregation. Why, 50 years after the Civil Rights movement, are our cities still segregated? Why do white families have over 10 times the net worth of black families? Why are whites almost twice as likely to own a home? Why are blacks twice as likely to be unemployed? Why are black babies 2.5 times more likely to die before their first birthday?

Race is real-ized through the same triad of forces that real-ize gender and blind men in the previous examples.

At the level of beliefs, studies show that Americans hold implicit biases even when they claim to deny all racial biases. For example, Yarka Mekawi and Konrad Bresin at the University of Illinois recently did a meta-analysis of the many studies involving the “shooter task” in which people are asked to shoot at video images of men with guns but avoid shooting men who are not holding guns. They found that across 42 studies, people were found to shoot armed black men faster than armed white men, and slower to decide to not shoot unarmed blacks. Such studies are increasingly important in an age of social media that has brought several police shootings of unarmed blacks under public scrutiny and inspired widespread protests such as the Black Lives Matter movement. These studies reveal that the stereotype that blacks are prone to anger and violence lays a claim on the consciousness of whites and blacks, even when those individuals are committed to overcoming racial bias.

Our beliefs, conscious and unconscious, affect our behavior. When researchers sent out identical resumes with only the names changed, they found that resumes with “white-sounding” names like Greg and Emily were 50% more likely to receive a call-back versus resumes with “black-sounding” names like Jamal and Lakisha.

These biases are often shared across races, so that blacks and whites hold the same stereotypes, and these stereotypes affect how they act and perform. For example, Jeff Stone at the University of Arizona set up a mini-golf course and announced to the players that it was specially designed to measure raw athletic ability. Black players outperformed white players. Then, without changing the course at all, he announced that the course was specially designed to measure one’s ability to see and interpret spatial geometry. White players outperformed black players.

But we fail to see how the ideas become real-ized without also looking at structure and the impact of institutionalized racism. Institutionalized racism is often misunderstood as institutions and laws that are overtly racist, or as an institution that is permeated with racists people or racist ideology. These misunderstandings lead people to claim that a city and its institutions cannot be described as having institutionalized racism if the city or its institutions are operated by blacks.

Institutionalized racism is better viewed not as the willful creation of racists or racist institutions, but as the cumulative effect of policies, systems and processes that may not have been designed with racism in mind, but which have the effect of disadvantaging certain racial groups.

For example, consider the insurance industry. Insurance companies do not usually have racist policies or overt racists working within them. In fact, when they are found to have any racist policies or racist employees, they face legal sanctioning. Nonetheless, they do have a set of policies that disadvantage blacks disproportionately to whites. They charge for auto-insurance based on ZIP code, which includes a calculation for how likely it is that your car might be stolen or damaged. Since more blacks live in poor, high-crime areas, this policy has the effect of disadvantaging them.

In many states and cities, school funding is also tied to ZIP code. It is also much more difficult to get a loan in some ZIP codes. Therefore, one of the most powerful forces that continuously re-creates racial prejudices is a structure that includes black poverty and segregated cities created after hundreds of years of slavery and official segregation. Even though official segregation is now a thing of the past, its legacy lives on as black families are more likely to live in poverty and in impoverished neighborhoods where it is more difficult to find and receive loans, a good education, and good opportunities. On average, blacks continue to have less wealth, less education, fewer opportunities, and live in impoverished areas with higher crime rates. These characteristics then get associated with blackness, thereby supporting the stereotypes that inform the practices that continually re-create the structure of segregation.

As Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton argued when coining the term “institutional racism,” we all rightly protest and take action when someone dies as the victim of a racist hate crime, but fail to see the problem when

“…five hundred black babies die each year because of the lack of power, food, shelter and medical facilities, and thousands more are destroyed and maimed physically, emotionally and intellectually because of conditions of poverty and discrimination in the black community …”

That was written over 50 years ago, in 1967. Black poverty in the inner city remains a problem, exacerbated by many historical trends and forces. Recognizing the triad of forces involved in real-ization (beliefs, behaviors, and structures) is essential to overcoming racim. If we only try to rid ourselves of our biased beliefs, we run the risk of not addressing important practices and structures that perpetuate those beliefs.

This potential to raise awareness, liberate our thinking, see our seeing, and potentially build a better world is why social scientists have been so excited about the idea of the social construction of reality for the past fifty years. But given that the future of reality is at stake, such discussions can become highly politicized and contentious, especially when the discussions might impact public policy or social norms.

This kind of investigation allows us to see into the processes through which our culture is made, and may even give us an opportunity to push back and re-make culture. But how far can this go? Can we really see the makings of our own realities and then just re-make them? This is not something to be answered in a single book, but to be continually discussed and debated in our everyday lives. Indeed, such a debate is the engine of culture and cultural change itself. However, we can make three important points of departure:

- Socially constructed realities shape and are shaped by physical reality in many complex ways.

- Because the future of reality is at stake, discussion and debate about socially constructed realities tend to be highly politically charged and contentious.

- Socially constructed realities are “made up” but they are still “real” and have real consequences. “Time” and “money” may be social constructions, but they are still really real. The fact that 2:30 pm is a social construction and part of a larger cultural set of beliefs emphasizing order and efficiency doesn’t mean you can blow off your 2:30 pm appointment to protest this set of social constructions and not face any social consequences.

LEARN MORE

Invisibilia Podcast: How to Become Batman

The Making of Blind Men, by Robert A. Scott

Delusions of Gender: How Our Minds, Society, and Neurosexism Create Difference, by Cordelia Fine

Skin: A Natural History, by Nina G. Jablonski

Race – The Power of an Illusion, www.pbs.org/race

Lesson 6 Social Structure

Most of what we take as “reality” is a cultural construction – “real-ized” through our unseen, unexamined assumptions of what is right, true, or possible.

6.1 Love In Four Cultures

Nimakot Village, Papua New Guinea