Lesson 7 Superstructure

We fail to examine our assumptions not just because they are hard to see, but also because they are safe and comfortable. They allow us to live with the flattering illusion that “I am the center of the universe, and what matters are my immediate needs and desires.”

7.1 Big Questions about Morality

The ideal marriage among the Sumbanese of Indonesia is for a woman to marry her father’s sister’s son, and for a man to marry his mother’s brother’s daughter. Like the marriages among the Tamil, these cousin marriages are arranged by elders and thought to be far too important to be left up to individual choice. These marriages create alliances between clans which are further reinforced through ceremonies involving an elaborate exchange of valuables such as horses, pigs, ivory, and gold. For the Sumbanese, this is simply the right thing to do.

One day, the anthropologist Web Keane was discussing these matters with an elder Sumbanese woman when she turned the tables and asked him about American marriage practices. Keane told her that individuals choose their own partners, that we rarely or never marry cousins but otherwise there are no rules, and that we do not host an elaborate exchange of goods like the Sumbanese. “She was visibly appalled,” Keane notes. With a sense of shock she exclaimed, “So Americans just mate like animals!”

On the surface, this story is a reminder of the vast differences between us. Our cultures seem to encapsulate very different morals, ethics, and values. Marriage practices are just one expression of what at root seem to be vastly different ideas and ideals. The American marriage system rests on ideals of individualism, freedom, liberty, and choice. If we really stop to imagine a young girl marrying her cousin at the behest of her elders, we can’t help but feel as appalled as the Sumbanese woman above. The Sumbanese system seems to be denying her most fundamental right to live a free life, fall in love, and pursue happiness under her own terms. But beneath the surface we might also perceive a few important similarities.First, both systems are supported by moral and ethical values. Americans may disagree on the specifics of the ethical system, but we recognize it as an ethical system and understand the value of such constraints. We might even agree with the sentiment that, as Keane summarizes it, “being ethical makes you human.”

The problem of different morals and ethics raises some challenging questions. As noted earlier, great questions can take us further than we ever thought possible. But questions can be disconcerting too, especially those that might lead us to question our moral and ethical foundations. Are there universal principles of right and wrong? Where does our morality come from? Does it have natural or divine origins? Are we born with a sense of morality or do we learn it? The implications of how we answer these questions will impact everything about how we live and find meaning and purpose in life. The stakes are high.

Morality provides many benefits to human societies. They keep people in line and allow us to live in relative peace and harmony. They can provide a sense of direction, meaning, and purpose. And they often put us in accord with the natural world around us as well, providing rules and directions for how to treat the world and the other creatures with whom we live.

But morality can also drive us apart. Many of the most intense conflicts and wars stem from real or perceived moral differences. Even within a single culture there can be virulent conflict over moral principles. As I write these words there are several protests planned in America today in the ongoing battles that have been dubbed the “culture wars.” The culture wars pit ardent conservatives against progressive liberals on issues of abortion, women’s rights, LGBTQ rights, free speech, political correctness, racial inequalities, global warming, and immigration, among many others. Over the past few years, the culture wars have become even more explosive, with protests and counter-protests often erupting into violence.

In the midst of these conflicts there is a growing sense that we simply cannot talk or have a civil discussion anymore. We live in different media worlds inside the filter bubbles created by social media. One person’s facts are another’s “alt-facts.” Is there any hope to find common ground?

In this lesson, we will be exploring the roots and many flourishing branches of morality, but ultimately our goal will be to use the anthropological perspective to try to see our own seeing, see big, and see small, so that we can “see it all” – see and understand our own moral foundations as well as those of others in hopes that we can have productive conversations with people who see the world differently. To do this, we will have to open ourselves up to the anthropological method to experience more (other moral ideas and systems), experience difference (by truly understanding the roots and foundations of those systems), and experience differently (by allowing ourselves to imagine our way into a new way of thinking, if only temporarily, to truly understand a different point of view).

IS THERE A UNIVERSAL MORALITY?

Imagine the following dilemma: A woman is dying and there is only one drug that can save her life. The druggist paid $200 for the materials and charges $2,000 for the drug. The woman’s husband, Heinz, asked everyone he knows for money but could only collect $1,000. He offered this to the druggist but the druggist refused. Desperate, Heinz broke into the lab and stole the drug for his wife. Should he have done this?

This is the famous Heinz dilemma, created by Lawrence Kohlberg to analyze how people think through a moral dilemma. Kohlberg was not interested in whether or not people thought Heinz acted morally. He wanted to know how they justified their answer. From their responses he was able to construct a six-stage theory of moral development proposing that over the course of a lifetime, people move from a “pre-conventional” self-centered morality based on obedience or self-interest to a more “conventional” group-oriented morality in which they value conformity to rules and the importance of law and order. Some people move past this “conventional” morality to a “post-conventional” humanistic morality based on human rights and universal human ethics.

Kohlberg proposed that these are universal stages of moral judgment that anyone in any culture may go through, but still allowed for a wide range of cultural variation in the group-oriented conventional stages based on local rules, customs, and laws. His post-conventional stages represent a universal morality but only a very few people can see their way past their own cultural conventions to see and act on them. In his studies, just 2% of people responded in a way that reflected a model of morality based on universal human ethics, and in practice he reserved the highest stage of moral development to moral luminaries like Gandhi and Mother Theresa.

However, some saw Kohlberg’s “universal” morality as biased toward a very specific model of morality that was culturally and politically biased in favor of liberal American values. By placing this “humanistic morality” as beyond and more developed than morality based on conformity or law and order he was placing his own cultural values at the pinnacle of human moral achievement. Kohlberg’s stage-theory model provided justification for a liberal secular worldview that championed questioning authority and egalitarianism as more advanced and developed than religiously-based moral worldviews that valued authority and tradition.

Then Kohlberg’s former student Elliot Turiel discovered that children as young as five often responded as “conventional” in some contexts but “post-conventional” in others. When children were asked whether or not it was okay to wear regular clothes to a school that requires school uniforms, kids said no, except in cases in which the teacher allowed it. The kids recognized that these rules were based on social conventions. But if you asked them if it was okay if a girl pushed a boy off a swing, the kids said no, and held to that answer even in cases in which the teacher allowed it or there were explicitly no rules against it. In this case, the kids were not basing their moral reasoning on social conventions. Turiel suggested that these were moral rules, not conventional rules, and moral rules were based on a universal moral truth: harm is wrong.

This moral truth discovered by Turiel as he analyzed the discourse of children reflects the wisdom of “The Golden Rule,” which is found in religious traditions all over the world. The words of Jesus (“Do unto others what you would have them do unto you.”) are echoed in the Analects of Confucius (“Do not do to others what you do not want them to do to you.”), the Udana-Varga of Buddhism (“Hurt not others in ways that you yourself would find hurtful.”) and the Hadiths of Islam (“None of you truly believes until he wishes for his brother what he wishes for himself.”), as well as many others. But evidence of a universal human morality might go beyond what is written in our texts. It might be written in our DNA.

THE NATURE OF HUMAN NATURE

Two dominant theories of human nature have been debated for centuries. One suggests that we are inherently good, peaceful, cooperative, empathic and nurturing. The other argues that we are inherently evil, violent, competitive, and selfish. In the 17th Century, Thomas Hobbes argued that our societies are composed of selfish individuals and that without a strong social contract enforced by government we would be engaged in a “war of all against all,” that we would be unable to cooperate to build technologies, institutions, and knowledge, and that ultimately our lives would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Against this conception stood Jean-Jacques Rousseau with his image of the Noble Savage living in accord with nature in peaceful and egalitarian communities beyond the corruption of power and society.

Many early popular anthropological accounts of indigenous people aligned with Rousseau’s vision. Countering popular stereotypes of violent “savages,” work such as that of Margaret Mead and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas portrayed indigenous people like the !Kung San as “The Harmless People” – hunter-gatherers living peaceful lives despite the absence of formal laws and governments.

However, over the past few decades anthropologists have acquired more detailed statistics on these groups, and the rates of violent death among hunter-gatherers appears much higher than what we find in large state-based societies, even when massive atrocities like the World Wars are taken into account. Violent death rates among males of the Jivaro and Yanomamo have been reported to be over 45%. Adding more data to the side that humans are inherently violent, anthropologist Carol Ember estimated that 64 percent of hunter-gatherer societies are either in a war or will be in one within the next two years. Under the weight of this evidence, linguist Steven Pinker declared that the “doctrine of the Noble Savage” had been “mercilessly debunked.”

But proponents of a better human nature note that just because we are naturally aggressive does not mean that we do not also have other important traits. Looking to our closest primate ancestors we find ample evidence of violent territorial behavior, but primatologist Franz de Waal sees a softer side as well. After a violent skirmish among chimpanzees he watched as the two fighters retreated to the tree tops. Soon one of them held out a hand in the direction of the other. They slowly moved closer to one another and reconciled with a hug. He had originally been tasked with studying aggression and conflict among chimps, but it was clear to him that chimpanzees valued their relationships and found ways to repair them when they were damaged.

In further field observations and lab tests, de Waal pieced together a vast array of evidence suggesting that primates exhibit two pillars upon which a more complex human morality can be built: empathy and reciprocity.

In one simple field test, he showed a looping video of a chimp yawning to see if chimps experience yawn contagion. Other studies among humans had shown that yawn contagion correlates with empathy. When chimps see a video of a chimp they know yawning, they “yawn like crazy” he says. This mimicry is a basic building block of empathy, an ability to imagine our way into another’s emotions and perspective.

This perspective-taking is of utmost necessity when cooperating on complex tasks and we find it not only in primates but other mammals as well. Chimpanzees and elephants are able to cooperate on the task of pulling in a food tray to obtain food. And chimpanzees will cooperate with another chimp even when there is nothing in it for them, showing that these actions go beyond mere selfishness.

In another study they let a chimpanzee purchase food with tokens. If the chimp paid with a red token, only they got food. If they paid with a green token, both the chimp and another chimp next door received food. If chimps were purely selfish, we would expect random selection of tokens, so that over time 50% would be red and 50% would be green. However, chimps tend to make prosocial choices by selecting the green token that fed the other chimp as well.

These pro-social tendencies extend into more elaborate notions of fairness as well. In a study of capuchin monkeys one monkey was paid in cucumber and the other in grapes. By the second round of payments the first monkey was furious and demanded fairness, throwing the cucumber back at the researcher and demanding the grape. Among chimpanzees the same test elicited even more complex behavior. The chimp receiving the grapes refused grapes until the other chimp also received grapes.

For decades, de Waal found himself struggling against a strong consensus among scientists that deep down, humans are violent, cruel, aggressive, and selfish. They proposed that only a thin veneer of human-made morality kept the world from falling apart. But his work was leading him somewhere else. Each experiment revealed that our evolutionary history had placed deep within us the capacity for empathy, cooperation, reconciliation, and a sense of fairness. “Our brains have been designed to blur the line between self and other,” de Waal noted on our capacity for empathy. “It is an ancient neural circuitry that marks every mammal, from mouse to elephant.”

De Waal seemed to be confirming Turiel’s findings. Turiel had found a basic universal morality in five-year-old children that showed that we place an innate value on fairness and see harm to others as inherently wrong. De Waal now found this same basic morality among monkeys and apes, suggesting that the foundations of our morality run very deep in our biology and evolutionary history.

THE PROBLEM OF CULTURAL VARIATION

Despite these apparent universals in the domains of harm and fairness, anthropologists did not need to look far to see a vast array of different moral standards reflected in the beliefs, practices, taboos, and rituals around the world. Aside from the most titillating accounts of human sacrifice, head-hunting, and ritualized cannibalism were many others that defied categorization into a simple scheme that placed principles of harm and fairness as the two pillars of morality.

In the 1980s, anthropologist Richard Shweder started working with Turiel to examine the cross-cultural evidence for a universal morality. Together, they determined that there was simply not enough evidence yet. They recognized that the five-year-olds may have simply picked up the principles of fairness and harm through socialization. They needed a more thorough study of moral development in other cultures to determine if these moral principles were made by nature or culture.

Shweder knew a great way to get started. He had done extensive fieldwork in the Hindu temple town of Bhubaneswar in India. As he describes it, it is

“…a place where marriages are arranged, not matters of ‘love’ or free choice, where, at least among Brahman families, widows may not remarry or wear colored clothing or ornaments or jewelry; where Untouchables are not allowed in the temple; where menstruating women may not sleep in the same bed as their husbands or enter the kitchen or touch their children; where ancestral spirits are fed on a daily basis; where husband and wives do not eat together and the communal family meals we find so important rarely occur; where women avoid their husbands’ elder brothers and men avoid their wives’ elder sisters, where, with the exception of holy men, corpses are cremated, never buried, and where the cow, the first ‘mother,’ is never carved up into sirloin, porterhouse or tenderloin cut.”

Note that it isn’t just the practices that strike the Western reader as strange, there are whole categories of persons and activities that run against our ideals of fairness and equality. The notion that there could be a whole class of people known as “Untouchables” runs counter to Western Enlightenment ideals of equality. To see what this could tell us about the possibility of universal morality, Shweder set up a study to compare the moral reasoning of Hindu Brahmans from Bhunabeswar with the people of Hyde Park, Illinois.

Shweder came up with 39 scenarios that he thought would be judged very differently between the two groups. For example, among the 39 scenarios the Brahman children thought the most serious moral transgression was one in which the eldest son gets a haircut and eats chicken the day after his father’s death. The second worst was eating beef, which was ranked worse than eating dog, which was only slightly worse than a widow eating fish. Other serious breaches as judged by the Brahman children included women who did not change their clothes after defecating and before cooking, a widow asking a man she loves to marry her, and a woman cooking rice and then eating it with her family. None of these, with the exception of eating dog, were seen as breaches by the children of Hyde Park.

Some of the disagreements between Brahmans and Americans reflected deeper and broader differences in basic moral vision. For example, Brahmans were deeply concerned about people modeling the behavior prescribed for them by their social role and position, while Americans prioritized equality and non-violence. Brahmans approved of beating a disobedient wife or caning a misbehaving child, while Americans found nothing wrong with the Brahman-disapproved behaviors of a woman eating with her husband’s elder brother or washing his plates.

So does this mean there is not a universal morality based on the foundations of harm and fairness? Turiel was not convinced. He pointed out that there was still strong agreement among Brahmans and Americans when it came to matters of harm and fairness. Both groups agreed that breaking promises, cutting in line, kicking a harmless animal, and stealing were wrong. As for the differences, Turiel argued that they could still fit within his model of universal morality because the cultural differences were just social conventions.

But Shweder’s research indicated that the locals did not see it this way. They saw their “social conventions” as moral imperatives. They were as real and obvious as Turiel’s foundations of harm and fairness. Behind these differences, Shweder argued that there was a profound difference not only in how Brahmans viewed morality, but also in how they think about the self, the mind, and the world.

Shweder proposed that the Brahmans were using three different moral systems as they evaluated different scenarios. The first he called the “ethic of autonomy.” This is the most familiar system to people in the West and the dominant ethic in individualistic cultures. The central idea is that people are autonomous individuals who should be able to pursue happiness so long as it does not impinge upon the happiness of others. Turiel’s “universal morality” is based in this ethic. Shweder’s point is that this apparently “universal” morality, while shared universally, is not the dominant moral system in other cultures.

The second moral system is the “ethic of community.” This one may take priority over the ethic of autonomy in more socio-centric cultures that emphasize the solidarity and well-being of the society, group, or nation over and above the individual. To maintain social order, this ethic emphasizes social roles, duties, customs, and traditions. Hierarchies are important, as are the values of respect and honor that may be required to uphold them. The emphasis on the ethic of community is what leads Brahmans to disagree with Americans on beating a disobedient wife or caning a misbehaving child.

The third moral system is the “ethic of divinity.” This system sees people as part and parcel of a world that requires constant and conscientious reverence to taboos, rules, and behaviors in line with a sacred worldview. Behaviors are judged not just in terms of whether or not they violate individual rights, but for how they might upset or fall in line with sacred rules, taboos, and prescriptions. This system explains the vast majority of differences between Brahmans and Americans, such as the food and behavior taboos.

Turiel and Shweder argued about how to interpret these cultural differences. Turiel continued to advocate for the idea that the behaviors Shweder categorized in these alternative ethical systems could be understood within a single, more simplified system based on rational assessments of individual harm and fairness if we just account for how Brahmans think. For example, he pointed out that the Brahman idea of reincarnation meant that they might be reasoning that breaking a taboo is wrong because it could lead to harm in a future life. If Brahmans were indeed doing this kind of calculation, the underlying moral decision would still be based on individualistic notions of harm and fairness.

WEIRD MORALITY

Jonathan Haidt had an idea about how to settle this debate. He invented scenarios that he called “harmless taboo stories” and shared them with research subjects of different backgrounds and education levels in Brazil and Pennsylvania to get their reactions. One story is about a man who purchases a chicken and has sex with the carcass before eating it. Another is about a woman tearing apart an American flag and using it to clean her house. Another is about a family eating a dog. Another is about a brother and sister having sex. In each case he is careful to arrange the facts in the story so that it is clear that there is no harm done to anyone, yet he also knows that it will trigger people’s sense of disgust and thereby create a moral dilemma as to whether or not it is write or wrong. If Turiel is right that all morality is ultimately based on harm and fairness, people should be able to see that their disgust is simply based on cultural conventions and ultimately reason that the people in the stories have done nothing wrong.

Out of 12 groups, all but one saw these “harmless” acts as moral violations. The rest were using different moral models based on community and divinity, supporting Shweder’s claims. The only one group that held true to Turiel’s model of moral reasoning was upper-class Americans at the University of Pennsylvania.

Cultural psychologists Joe Henrich, Steve Heine, and Ara Norenzayan would later call this group of people “the weirdest people in the world,” using the acronym WEIRD to define them as Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic. Haidt’s study showed that the WEIRDer you are, the more likely you are to stick to Turiel’s model of moral reasoning based solely on the ethic of autonomy when making a moral decision. But it turns out that if you want to make inferences about human nature, WEIRD people may be the least typical and representative sample of humans on the planet.

As Haidt summarizes it, the key difference between WEIRD people and most other cultures is that WEIRD people “see a world full of separate objects, rather than relationships.” This includes the individual, who is seen not in terms of their relationships but instead as an entity separate and unto itself. As anthropologist Clifford Geertz has noted,

The Western conception of the person as a bounded, unique, more or less integrated motivational and cognitive universe, a dynamic center of awareness, emotion, judgment, and action organized into a distinctive whole and against its social and natural background, is, however incorrigible it may seem to us, a rather peculiar idea within the context of the world’s cultures.

Richard Shweder proposed that this “egocentric” or individualistic view of the world and the moral reasoning that went along with it were historically and culturally rare, fostered during the Western Enlightenment and rising to prominence in the 20th Century. Most cultures are more “sociocentric,” emphasizing the need for social order, solidarity, rules and roles above individual needs and desires.

Haidt wanted to immerse himself in a more sociocentric culture to better understand their morality, so he teamed up with Shweder and went to Bhunabeswar. Emulating the open-minded anthropologists that inspired his trip, Haidt immersed himself in local life, and very soon felt the feelings of dissonance and shock that can come when someone crosses over into a very different cultural world. He immediately felt the conflicts between his moral world and the one he had just entered. His egalitarian ethos made him uncomfortable with having servants. He had to be told to be stricter with them and stop thanking them. “I was immersed in a sex-segregated, hierarchically stratified, devoutly religious society,” he writes, “and I was committed to understanding it on its own terms, not mine.”

Tourists often move about among other tourists. A tourist in India might briefly interact with the local culture, but will often find themselves on that same day telling a story about the interaction, and falling back into common Western assumptions to explain and describe what they saw. Full cultural immersion over several weeks or months allowed Haidt to start to see the world more as the locals saw it.

He credits his ability to break past his WEIRD biases and assumptions on a simple fact: he liked the people he was living with in India. They were helpful, kind, and patient, and they became his friends. So even though he would normally reject their hierarchical rules as oppressive and sometimes sexist, he found himself leaning in a little further to understand them, rather than immediately discounting them.

As he did, he saw a completely different set of assumptions and values supporting the system. Rather than equality and individual rights as sacred values, it was the honoring of elders, rules, and gods that mattered most. Rather than striving to express one’s unique identity, they strove to fulfill their respective roles. He had understood Shweder’s argument intellectually, but now he began to feel it. “I could see beauty in a moral code that emphasizes duty, respect for one’s elders, service to the group, and negation of the self’s desires.” He was not blind to the downsides of their system – the potential abuse of women, Untouchables, and others who were low in the hierarchy – but it also made him aware of the downsides of his own moral system. “From the vantage point of the ethic of community, the ethic of autonomy now seemed overly individualistic and self-focused.”

THE FOUNDATIONS OF MORALITY

Haidt noticed something peculiar as his research subjects responded to his harmless taboo stories. All of them, even the WEIRD ones, had immediate responses of disgust. Only after these initial responses did they start struggling to come up with moral reasonings to support their feelings. It was as if they were making quick and intuitive moral judgments and then searching for reasons after the fact. At the time, most research had assumed that morality was based in moral reasoning. It was assumed that people consciously considered their moral values and then made decisions based on these conscious deliberations. Haidt suspected that morality was more intuitive, and that the seat of morality rested in the emotions, not in the intellect.

In one study, he had his research team stand on street corners with fart spray. They would spray a little bit and then pose moral dilemmas to passers-by using his harmless taboo stories. It turns out that when people are immersed in a cloud of fart, they make harsher moral judgments. Haidt proposed that the fart spray was triggering the emotion of disgust. The intellect then tried to explain this emotion using moral reasoning. Contrary to popular belief, Haidt was showing that reasoning does not lead to moral judgment. It is the other way around. We use reasoning to explain our judgments, not to make them. He modeled it like this:

Haidt found additional support for his “intuitionist model of morality” in the studies of primates by Frans de Waal. After all, if conscious moral reasoning was necessary for morality, how could monkeys demand fairness or empathize with someone who has been harmed? Other studies showed that moral philosophers, people who spend their whole lives studying and sharpening their capacities for moral reasoning, are no more moral than anyone else. Just as one does not need to know and name the specific rules of grammar that make a language work in order to speak a language, people (and other apes) do not need moral reasoning to act morally.

If these moral intuitions lie deeper in the brain and our moral reasoning is at least partially shared by our primate cousins, it would follow that our moral capacities are innate and part of our evolutionary heritage. But instead of proposing a universal morality, Haidt and his colleagues proposed that humans may have universal moral “taste receptors.” Using the metaphor of the tongue and its taste receptors, Haidt pointed out that humans all share five tastes (salty, sweet, bitter, sour, and umami) and yet build a wide-range of different cuisines to satisfy them. Similarly, moral “taste receptors” could serve as the backdrop upon which thousands of different moral systems could develop. Breaking through the nature-nurture debate, Haidt found a model that accommodated the exciting findings of primatologists that suggested a universal human morality while still making room for the vast range of cultural variation found by anthropologists.

Haidt and his colleagues proposed six foundations of morality that developed through the process of evolution as our ancestors faced the challenges of living and reproducing.

1. Care/harm. Emotions: Empathy, Sympathy, Compassion. Developed to protect and care for vulnerable children, we feel compassion for those who are suffering or in distress.

2. Fairness/cheating. Emotions: Anger, Gratitude, Guilt. Developed to reap the benefits of reciprocity, we feel anger when somebody cheats, gratitude when they cooperate, and guilty when we deceive others.

3. Loyalty/betrayal. Emotions: Pride, Rage, Ecstasy. Developed to form coalitions that could compete with other coalitions, we feel a sense of group pride and loyalty with our in-group and a sense of rage when someone acts as a traitor. Group rituals also give us a sense of ecstasy and make us feel part of something bigger than ourselves.

4. Authority/subversion. Emotions: Obedience, Respect. Developed to forge beneficial relationships within hierarchies, we feel a sense of respect or fear toward people above us in a hierarchy, fostering a sense of obedience and deference.

5. Sanctity/degradation. Emotions: Disgust and Aversion. Developed to avoid poisons, parasites, and other contaminants, we feel a sense of disgust toward the unclean, especially bodily waste and blood.

6. Liberty/oppression. Emotion: Righteous anger/reactance. Developed to maintain trust and cooperation in small groups, we feel a sense of righteous anger and unite with others in our group to resist any sign of oppression.

Think of these as our moral “taste receptors.” Just as people have different personal tastes that develop within larger cultural systems, so it is also true for morality. We all grow up within a certain moral culture that shapes our moral tastes, but we also have personal differences in tastes.

UNDERSTAND OTHER MORALITIES

One of the greatest gifts of ethnographic fieldwork, immersion in a foreign culture, and careful study of the human condition is that it allows you to see your own culture in a new way. Haidt was raised in a liberal household in a liberal city and went to school at a liberal college. By his own account, he was immersed in a liberal bubble. The Left was his native culture. “I was a twenty-nine-year-old liberal atheist with very definite views about right and wrong,” he writes. But after his visit to India and his ongoing studies of morality, he started to see Republicans and other conservatives with a more open mind.

He had always been a liberal, because he saw it as the group that advocates for equality and fairness for all individuals regardless of their background. How could anyone be against equality? he wondered. He assumed that conservatives must just be selfish, prejudiced, and/or racist. Why else would conservatives want to lower taxes and strip away funding to help the poor?

But when he came back from India and started researching the foundations of morality, he found that he was starting to understand why people on the religious right would fight for more traditional values and social structures. He had gone to the other side of the world to get a glimpse of people with a radically different morality to his own. Now he realized that such people were all around him. And with the culture wars heating up as Democrats and Republicans yelled right past each other into gridlock, Haidt wanted more than ever to understand the roots of these alternative moralities to see if he could help both sides understand one another a little better.

He set up a questionnaire to assess how people varied in their moral “tastes,” and thanks to some good press about his project in the New York Times, over 100,000 people participated. The results showed substantial differences in what factors and values liberals and conservatives consider when making moral decisions.

In short, liberals focus primarily on just three foundations (Care, Fairness, and Liberty) while conservatives equally consider all six. Moreover, liberals see the other three (Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity) as potentially immoral, because they constrain their pursuit of their most sacred value: caring for victims of oppression. If we want equality for all, we have to dissolve groupishness (Loyalty), undermine hierarchy (Authority), and never press one group’s sacred values upon others (Sanctity).

However, until Haidt did his study, he (like other liberals) did not even recognize these other three moral foundations, and this led him to misunderstand and misjudge conservatives. Conservative stances against immigrants, programs to help the poor, gay marriage, feminism, and the rights of oppressed groups lead many liberals to assume that conservatives are simply heartless and selfish. However, these mis-judgments arise because liberals judge conservative morality on the basis of just three of the six foundations, which makes it seem like the conservatives do not care about other races and ethnicities, poor people, immigrants, women, and gay people.

To test this idea, Haidt asked his liberal study participants whether conservatives would agree or disagree with the statement “One of the worst things a person can do is hurt a defenseless animal.” Liberals thought conservatives would disagree, demonstrating that liberals think conservatives are heartless and selfish. They fail to see that conservatives are pursuing a broader range of positive moral values, and that there may be some merit to what they bring to our political discussions.

Ultimately, Haidt sees that at the root of these opposing moral visions are two very different views of society and human nature, and they are the same two views that we have been arguing about for centuries that were presented in the opening of this chapter. Stephen Pinker calls them the Utopian Vision and the Tragic Vision. The Left takes the utopian view. We are good in our core, but the biases and assumptions of our cultures and societies corrupt us. We are limited from achieving a better world by socially constructed rules, roles, laws, and institutions that are oppressive to some groups and identities among us. We can create a more just, free, and equal society by recognizing how these things are constructed, thereby setting ourselves free from bias, bigotry, and oppression.

The Right takes a more tragic view of society and human nature. They see humans as constrained and limited in their moral capacities and abilities. We are naturally prone to violence, tribalism, and selfishness. If we eliminated hierarchies, we would just re-create them in new forms because of our will to power and desire for self-preservation. The only thing that keeps the world from falling apart into violent chaos is the system of rules, traditions, moral values, and social institutions. We should be careful in our attempts to mess with these precious (and for many, divine) moral institutions that hold our fragile society together.

As Haidt started to see, understand, and empathize with the conservative perspective, he found himself “stepping out of the Matrix” and taking “the red pill.” He did not “turn red” and become a conservative, but he could now genuinely appreciate their perspective and actually listen to their views with true understanding. This opened him up to many new and exciting ideas for solving major social problems that he had never considered before.

From his work we can find five good reasons to challenge ourselves to open up and try to understand and even appreciate the arguments coming from the other side of the political aisle.

1. Both sides offer wisdom.

On the Left, the wisdom centers on caring for the victims of oppression and constraining the powerful. The Left seeks to offer equal opportunity for all, which has obvious merit based on universal principles of harm and fairness. But there is also an important utilitarian aspect to the argument. There is tremendous wasted human potential right now in disadvantaged places (impoverished inner cities, rural towns, migrant worker camps, refugee camps). Providing adequate support and opportunity in these places could add tremendous value to society by unleashing the potential of more people.

The Right offers the wisdom of markets. Societies have grown beyond the capacity for any one person or small group to understand and manage. Markets allow millions and sometimes billions of people to participate in the essential, minute decisions of production, pricing, and distribution of goods. What emerges is a super-organism that is greater than the sum of its parts.

The Right also offers the wisdom of moral order and stability. Societies function best when there is a sense of solidarity and trust among members, and this can be nurtured through shared values, virtues, norms and a shared sense of identity.

2. They each reveal the blind spots in the other. Liberals have a blind spot that makes it difficult for them to see the importance of shared moral principles, values, and virtues that uphold our traditional practices and institutions. Pushing for change too fast can be dangerously disruptive and divisive. On the other hand, conservatives fail to see how these traditional practices and institutions might oppress certain groups or identities and may need to reform or change along with other cultural changes.

3. Our political differences are natural and unavoidable.

Our moral judgments are based in our intuitive emotional responses that are beyond conscious control. Since our emotional responses vary along with our personalities, we cannot expect everyone to agree, and it should not seem unusual to find that a two party political system would so consistently break somewhere close to 50/50 in every election.

Furthermore, studies of identical twins separated at birth and raised in different households suggest that our genetics can explain one-third to one-half of the variability of our political attitudes. Genes shape our personalities, which in turn shape which way we will lean politically. This genetic effect is actually stronger than the effect of how and where we are raised.

4. Our political differences are an essential adaptation.

Humans have not survived and thrived alone. We have survived as a species with many different personality types, and because we are a species with many different personality types. Some personalities are open to new experiences and people. Others are more careful and fearful. We have survived through many millennia thanks to the balance of these traits. We should be grateful to those who are different from us, for they offer important checks and balances against our own limited vision and understanding.

5. There are many dangers to Us vs. Them thinking.

Our tendency to create in-groups lead us into political “bubbles” where we only encounter the safe and familiar ideas of our political “tribe.” When we encounter an idea that is associated with the other tribe, our immediate reaction is one of disgust. We then use our moral reasoning to explain our reaction, finding reasons to reject the idea even if it is a good one that could serve our highest ideals. Likewise, we will have warm feelings toward any idea put forth as one that supports our political leanings. We will then search for reasons to accept the idea. In the age of Google, it is all too easy to find research and reasons to support any idea, thereby strengthening our biases and assumptions.

As Haidt so eloquently and concisely states, “morality binds and blinds.” Our moral inclinations bind us together and then blind us to the other.

LEARN MORE

The Righteous Mind, by Jonathan Haidt

Thinking Through Cultures: Expeditions in Cultural Psychology, by Richard Shweder

Ethical Life: Its Natural and Social Histories, by Webb Keane

7.2 The Dynamics Of Culture

All cultures are dynamic and constantly changing as individuals navigate and negotiate the beliefs, values, ideas, ideals, norms, and meaning systems that make up the cultural environment in which they live. The dynamics between liberals and conservatives that constantly shape and re-shape American politics is just one example. Our realities are ultimately shaped not only in the realm of politics and policy-making, but in the most mundane moments of everyday life.

Anthropologist Clifford Geertz famously noted, echoing Max Weber, that “Man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun.” These webs of significance create a vast network of associations that create the system that brings meaning to the most minute moments of our lives and dramatically shape the decisions we make. Due to these “webs of significance,” even the simple decision of which coffee to drink can feel like a political decision or some deep representation of who we are as a person.

In a recent BuzzFeed video, a woman sits down for a blind taste test of popular coffees from Dunkin’ Donuts, Starbucks, McDonalds, and 7-11. As she sits, the young woman confidently announces her love for Dunkin Donuts coffee. “Dunkin’ is my jam!” she says, declaring not only her love for the coffee but also expressing her carefree and expressive identity. But as she takes her first sip from the unmarked cup of Dunkin’ Donuts coffee she nearly spits it out and screams, “This is the worst!” and then confidently proclaims that that cup had to be ”7-11!” She eventually settles on the 4th cup from the left as the best. When she is told that she has chosen Starbucks, it seems to create a minor identity crisis. She covers her head in shame, ”Oh my god, I’m so against big business.” Her friend, who has also chosen Starbucks, looks to the sky as if having a revelation about who he is. ”We’re basic,” he says. “We’re basic,” she repeats, lowering her head in shame and crying with just enough laugh to let us know that she is kidding, but only kind of kidding.

Another woman, elegantly dressed in a black dress with a matching black pullover and a bold pendant, picks McDonald’s – obviously well “below” her sophisticated tastes. She throws her head back in anguish and then buries her head in her hands as she cries hysterically, but a little too hysterically for us to take it too seriously. She wants us to know that this violates her basic sense of who she is, but that she is also the type of person who can laugh at herself.

The point is that what tastes good to us – our taste for coffee, food, music, fashion, or whatever else – is not just a simple biological reaction. There is some of that, of course. We are not faking it when we enjoy a certain type of music or drink a certain type of coffee. The joy is real. But this joy itself is shaped by social and cultural factors. What tastes good to us or strikes us as beautiful or “cool” is shaped by what it means to us and what it might say about us.

The simple “high school” version of this is to say that we are all trying to be cool, and though we may try to deny it as we get older, we never stop playing the game. We are constantly trying to (1) shape our taste to be cool, or (2) shaping “cool” to suit our taste. Replace the word “cool” with “culture” and you see that we have one of the fundamental drivers of cultural change. We shape our taste (which could include our taste in food, politics, rules, roles, beliefs, ideals) to be acceptable, while also attempting to shape what is acceptable (culture) to suit our tastes.

WHY SOMETHING MEANS WHAT IT MEANS

In 2008, Canadian satirist Christian Lander took aim at the emerging cultural movement of “urban hipsters” with a blog he called “Stuff White People Like.” The hipster was an emerging archetype of “cool” and Landers had a keen eye for outlining its form, and poking fun at it. The blog quickly raced to over 40 million views and was quickly followed by two bestselling books.

In post #130 he notes the hipster’s affection for Ray-Ban Wayfarer sunglasses. “These sunglasses are so popular now that you cannot swing a canvas bag at a farmer’s market without hitting a pair,” Lander quips. He jokes that at outdoor gatherings you can count the number of Wayfarers “so you can determine exactly how white the event is.” If you don’t see any Wayfarers, “you are either at a Country music concert or you are indoors.”

Here Landers demonstrates a core insight about our webs of significance and why something means what it means. Things gather some of their meaning by their affiliation with some things as well as their distance from other things. In this example, Wayfarers are affiliated with canvas bags and farmers markets, but not Country music concerts. The meaning of Wayfarers is influenced by both affiliation and distance. They may not be seen at Country music concerts, but part of their meaning and significance depends on this fact. If Country music fans suddenly took a strong liking to Wayfarers, urban hipsters might find themselves disliking them, as they might sense that the Wayfarers are now “sending the wrong message” through these associations with Country music.

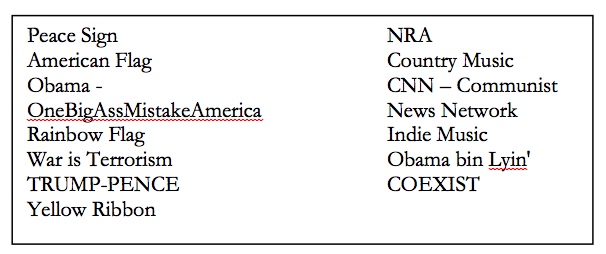

A quick quiz can demonstrate how this plays out in the American Culture Wars. Imagine you are sitting in traffic behind a Toyota Prius. In the left lane in front of you is a pickup truck, jacked up with extra-large tires. Both are covered in bumper stickers and you can overhear the music playing inside. Can you match the stickers and music with the vehicle?

Of course you can. Symbols hang together. They mean what they mean based on their similarity and differences, their affiliations and oppositions. So the meaning of OneBigAssMistakeAmerica gains some of its meaning from being affiliated with the truck and not with the Prius. The cultural value of the truck and Prius depend on their opposition to one another. They may be in very different regions of the giant web of culture, but they are in the same web. It isn’t that there are no Indie music fans who hate Trump and drive trucks. Some of them do. But they know, and you know, that they are exceptions to the pattern.

The meaning of symbols is not a matter of personal opinion. Meanings are not subjective. But they are not objective either. You cannot point to a meaning out in the world. Instead, cultural meanings are intersubjective. They are shared understandings. We may not like the same music or the same bumper stickers, but the meanings of these things are intersubjective, or in other words, I know that you know that I know what they mean.

At some level there is broad agreement of meanings across a culture. This facilitates basic conversation. If I gesture with my hands in a certain way, I can usually reasonably assume that you know that I know that you know what I mean. But the web of culture is also constantly being challenged and changed through the complex dynamics of everyday life. The web of culture does not definitively dictate the meaning of something, nor does it stand still. We are all constantly playing with the web as we seek our own meaningful life.

We use meanings and tastes as strategic tools to better our position in society and build a meaningful life, but as we do so, we unwillingly perpetuate and reproduce the social structure with all of its social divisions, racial divides, haves and have-nots. This is the generative core of culture. In Lesson Six, we explored the idea that “we make the world.” In this lesson we start digging into the mystery of how we make the world.

TASTE AND DISTINCTION

Why do you like some music and hate others? Why do you like that certain brand of coffee, that soft drink, those shoes, clothes, that particular car? In a famous study published in 1979, French anthropologist Pierre Bourdieu put forth the idea that our tastes are strategic tools we use to set ourselves apart from some while affiliating with others. Taste is the pursuit of “distinction,” the title of his book.

Bourdieu needed to invent new concepts to explain how taste and distinction work within a society. He pointed out that tastes have cultural value. The right taste can be an important asset as you make your way through society and try to climb the social ladder. So he invented the notion of “cultural capital” to refer to your cultural knowledge (what you know), “social capital” to refer to your social network (who you know) and pointed out (importantly) that what you know and who you know play a strong role over the course of a lifetime in how much you own (economic capital) and your social status.

Cultural capital includes your ability to catch the passing reference to books, movies, and music of the cultural set you aspire to be a part of during a conversation. It includes your capacity to talk with the right words in the right accent about the right things. It includes your ability to dress right, act right, and move right. And it includes your taste, an ability to enjoy the right music, foods, drinks, movies, books, and fashion, among other things.

What is “right” for one person is not necessarily “right” for another. If you aspire to be an affluent urban intellectual hipster, the cultural capital you will set about accumulating is very different from the cultural capital sought after by someone pursuing acceptance as authentically Country. Importantly, this distinction between the two sets is essential to the vitality of each. As Carl Wilson explains, “you want your taste affirmed by your peers and those you admire, but it’s just as vital that your redneck uncle thinks you’re an idiot to like that rap shit. It proves that you’ve distinguished yourself from him successfully, and you can bask in righteous satisfaction.”

THE CYCLE OF COOL

Cultural capital, like economic capital, is scarce. There is only so much time in a day to accumulate cultural capital, and most of us spend a great deal of our time pursuing it, recognizing its importance in our overall social standing. But cultural capital – what is “cool” – is always on the move. Capital attains its value by being scarce. Cultural capital – “what is cool” – maintains this scarcity by always being on the move. Being cool is a full-time job of carefully watching for trends and movement in the webs of significance we are collectively spinning.

Market researchers try to keep up with what is cool by tracking down trend-setting kids to interview them, study them, and follow them on social media. Once market researchers get in on a trend, they can create products to serve this new taste; but as soon as the mass consumer picks up on it, the trend-setter can no longer like it without being associated with the masses. Doug Rushkoff calls this the “cycle of cool.” Once that “cool” thing is embraced by the masses, it’s not cool anymore, because it’s no longer allowing people to feel that sense of distinction. Trend setters move on to the next cool thing, so that the mark of what is “cool” keeps moving.

Market researchers are also employed by media companies producing movies, TV shows, and music videos that need to reflect what is currently popular. In Merchants of Cool, a documentary about the dynamics of cool and culture in the early 2000s, Doug Rushkoff asks, “Is the media really reflecting the world of kids, or is it the other way around?” He is struck by a group of 13-year-olds who spontaneously broke out into sexually-laden dances for his camera crew the moment they started filming “as if to sell back to us, the media, what we had sold to them.” He called it “the feedback loop.” The media studies kids and produces an image of them to sell back to the kids. The kids consume those images and then aspire to be what they see. The media sees that and then crafts new images to sell to them “and so on … Is there any way to escape the feedback loop?” Rushkoff asks.

He found some kids in Detroit, fans of a rage rock band called Insane Clown Posse. They thought they had found a way to get out of the media machine by creating a sub-culture that was so offensive as to be indigestible by the media. With his cameras rolling, the kids yell obscenities into the camera and break out singing one of their favorite and least digestible Insane Clown Posse songs, “Who’s goin ti**y f*in?” one boy yells out and the crowd responds, “We’s goin ti**y f*in!” They call themselves Juggalos. They have their own slang and idioms, and they feel like they have found something that is exclusively theirs. “These are the extremes that teens are willing to go to ensure the authenticity of their own scene,” Rushkoff concludes. “It’s a double dog dare to the mainstream marketing machine,” Rushkoff notes, “Just try to market this.”

They did. Before Rushkoff could finish the documentary, the band had been signed by a major label, debuting at #20 on the pop charts.

WHY WE HATE

Growing up in a small town in Nebraska, I learned to hate Country music. One would think it would be the opposite. Nebraskans love Country music. But that was precisely the point. By the time I was a teenager, I had aspirations of escaping that little town. I wanted to go off to college, preferably out of state, and “make something of myself.” The most popular Country song of that time was by Garth Brooks singing, “I’ve Got Friends in Low Places.” I didn’t want friends in low places. I wanted friends (social capital) in other places, high places, so I tuned my taste (cultural capital) accordingly. I hated Garth Brooks. I hated Country music.

I loved Weezer. Weezer was a bunch of elite Ivy League school kids who sang lyrics like, “Beverly Hills! That’s where I want to be!” It was like a soundtrack for the life I wanted to live. “Where I come from isn’t all that great,” they sang, “my automobile is a piece of crap. My fashion sense is a little whack and my friends are just as screwy as me.” It seemed to capture everything I was, and everything I aspired to become.

My hatred for Country music bore deep into my consciousness as I associated it with a wide range of characteristics, values, beliefs, ideas, and ideals that I rejected and wanted to distinguish myself from. The hate stuck with me so that years later, I still could not stand to stay on a Country music station for long. I once heard a bit of a Kenny Chesney song about knocking a girl up and getting stuck in his small town. “So much for ditching this town and hanging out on the coast,” the song goes, “There goes my life.” Ha! I thought. I got out. Then I changed the channel.

Of course, nurturing such hatreds is not especially conducive to being a good anthropologist, or a good human being for that matter. What can we do? Is it possible to overcome our hatreds? And if we can do it with music, can we do it with hatreds of more substance and importance? Can we get beyond hatreds of others, other religions, other cultures, other political beliefs? And can we do it without giving up all that we value and hold dear?

Carl Wilson, a Canadian music critic, decided to do an experiment to explore these questions. He called it “an experiment in taste.” He would deliberately try to step outside of his own taste-bubble and try to enjoy something he truly hates. His plan was to immerse himself in music he hates to find out what he can learn about taste and how it works.

As he thought about what he hated most, one song immediately came to mind: Celine Dion’s “My Heart Will Go On.” The song rocketed to international popularity as the love song of the blockbuster movie Titanic in 1998. The song, and Celine Dion herself, have enjoyed global success that is almost unrivaled by any other song or celebrity. She sells out the largest venues all over the world. As the US entered Afghanistan in 2003, The Chicago Tribune noted that Celine was playing in market stalls everywhere, her albums being sold right beside Titanic-branded body sprays, mosquito repellant … even cucumbers and potatoes were labeled “Titanic” if they were especially large.

As a Canadian music critic with a vested interest in being cool among affluent urban intellectual hipsters, Wilson could not think of any song he hated more. In general, urban hipsters like Wilson love to bash Celine, and especially this song. Maxim put it at #3 in its ranking of “most annoying song ever” and called it “the second most tragic event to result from that fabled ocean liner.”

Wilson quotes Suck.com for calling Titanic a “14-hour-long piece of cinematic vaudeville” that teaches important lessons “like if you are incredibly good-looking, you’ll fall in love.”

Wilson’s hate for the song crystallized at the Oscars in 1998. Up against Celine’s love ballad was Elliot Smith’s “Miss Misery” a soul-filled indie love song about depression from Good Will Hunting that you would expect to hear from the corner of an authentic hip urban coffee shop. Smith was totally out of place at the Oscars. He didn’t even want to be there. It wasn’t his scene. He reluctantly agreed to sing when the producers threatened to bring in ’80s teen heart throb Richard Marx to sing it instead. As a compromise, he performed the song alone with nothing but his guitar. It wasn’t his kind of scene, but he would still do his kind of performance.

Then Celine Dion came “swooshing out in clouds of fake fog” with a “white-tailed orchestra arrayed to look like they were on the deck of the Titanic itself.” Elliot’s performance floated gently like a hand-carved fishing boat next to the Titanic performance of Celine. Madonna opened the envelope to announce the winner, laughed, and said with great sarcasm, “What a shocker … Celine Dion!” Carl Wilson was crushed, and his hate for Celine, and especially that song, solidified.

Wilson did not need to probe the depths of his consciousness to know that he hated that song, but he still did not know why he hated that song. Perhaps Bourdieu’s terminology could help, he mused. Turning to the notions of social and cultural capital, he started exploring Celine Dion’s fan base to see if he was using cultural capital to distinguish himself from some groups while affiliating himself with others.

He was not the first to wonder who likes Celine Dion. He quoted one paper (The Independent on Sunday) as offering the snarky musing that “wedged between vomit and indifference there must be a fan base: … grannies, tux-wearers, overweight children, mobile-phone salesmen, and shopping-centre devotees, presumably.” Looking at actual record sales, Wilson found that 45% were over 50, 68% female, and that they were 3.5 times more likely to be widowed. “It’s hard to imagine an audience that could confer less cool on a musician,” Wilson mused. It was no wonder he was pushing them away by pushing away from the music.

But he also noted that the record sales showed that they were mostly middle income with middle education, not unlike Wilson himself. Wilson aspires to be an intellectual and tries to write for an intellectual audience, but he has no clear intellectual credentials such as a Ph.D., and his income reflects this.

This brings up an important point about the things we hate: We often hate most that which is most like us. We have elevated anxieties about being associated with things that people might assume we would like, so we make extra efforts to distinguish ourselves from these elements. So Wilson pushes extra hard against these middle-income middle-educated Celine fans while attempting to pull himself toward the intellectual elite.

This is not as simple as an intentional decision to dislike something just because it isn’t cool. It works at a much deeper level. The intellectual elite that Wilson aspires to be associated with talks and acts in certain ways. They have what Bourdieu calls a certain “habitus” – dispositions, habits, tastes, attitudes, and abilities. In particular, the intellectual elite tend to over-intellectualize and deny emotion. Nurturing this same habitus, Wilson hears a simple sappy love ballad on a blockbuster movie loved by the masses and immediately rejects it. It doesn’t feel intentional. He truly hates it, and that hatred is in part born out of this habitus.

HOW TO STOP HATING

Wilson pressed forward with his experiment. He met Celine’s fans, including a man named Sophoan, who was as different from Wilson as possible. He is sweet-natured and loves contemporary Christian music, as well as the winners of various international Idol competitions. “I’m on the phone to a parallel universe,” Wilson mused about their first phone conversation. But by the end of it, he genuinely likes Sophoan, and he is starting to question his own tastes. “I like him so much that for a long moment, his taste seems superior,” Wilson concludes. “What was the point again of all that nasty, life-negating crap I like?”

As Wilson explored his own consciousness a bit deeper, he started to realize just how emotionally stunted he had become. He had just been through a tough divorce. It wasn’t that he felt no emotion; it was that his constant tendency to over-intellectualize allowed him to never truly sit with an emotion and really feel it. Instead he would “mess with it and craft it … bargain with it until it becomes something else.”

Onward with the experiment. Wilson decided to listen to Celine Dion as often as possible. It took him months before he could play it at full volume, for fear of what his neighbors might think of him. He had developed, as he put it, a guilty pleasure. And the use of the word “pleasure” was intentional. He really was starting to enjoy Celine Dion.

“My Heart Will Go On” was more challenging, though. It wasn’t just that it had reached such widespread acceptance among the masses. It was that it had been overplayed too much to enjoy. “Through the billowing familiarity,” he writes, “I find the song near-impossible to see, much less cry about.”

That is, until it appeared in the TV show Gilmore Girls. After the divorce, Wilson found himself drawn to teenage drama shows. His own life was not unlike that of those teenage girls portrayed in the shows. Single and working as a music critic, he often goes out to shows and parties where he always struggles to fit in, find love, and feel cool among people who always seem to be a little cooler than him.

In the last season of Gilmore Girls, the shihtzu dog of the French concierge dies. The concierge is a huge Celine fan, and requests “My Heart Will Go On” for the funeral. The whole scene is one of gross and almost ridiculous sentimentality, but a deep truth is expressed through Lorelai, the lead character, as it dawns on her that her love for her own husband is not as deep or true as the love this concierge has for his dog. She knows it’s time to move on and ask for a divorce. Wilson starts to cry:

Something has shifted. I’m no longer watching a show about a teenage girl, whether mother or daughter. It’s become one about an adult, my age, admitting that to forge a decent happiness, you can’t keep trying to bend all the rules; you aren’t exempt from the laws of motion that make the world turn. And one of the minor ones is that people need sentimental songs to marry, mourn, and break up to, and this place they hold matters more than anything intrinsic to the songs themselves. In fact, when one of those weepy widescreen ballads lands just so, it can wise you up that you’re just one more dumb dog that has to do its best to make things right until one day, it dies. And that’s sad. Sad enough to make you cry. Even to cry along with Celine Dion.

I think back to my own experience with that Kenny Chesney song – the one about the guy getting stuck in the small town after getting a girl pregnant. After I became a father, I was driving home from a conference, back to be with my wife and infant son in Kansas. (We felt drawn back to small town life, and decided to settle close to home to start our family.) The singer describes his little girl smiling up at him as she stumbles up the stairs and “he smiles … There goes my life.” I, of course, am weeping uncontrollably at this point. I’m a different person. The song speaks to me, and completely wrecks me in a later verse as the chorus is invoked one last time in describing his little girl going off to college. There goes my life. There goes my future, my everything, I love you, Baby good-bye. There goes my life. (I can’t even type the words without crying.)

Like me, Wilson once hated that sappy music. But now, he says, “I don’t see the advantage in holding yourself above things; down on the surface is where the action is.” By opening himself up to experiencing more, experiencing difference, and experiencing differently, Carl Wilson became more. He expanded his potential for authentic connection—not just to music, but also to other people. In his efforts to be cool, he spent a great deal of time trying to not be taken in by the latest mass craze, unaware that he was “also refusing an invitation out.” The experiment allowed him to move beyond this, open up to new experiences and more people. He started to see that the next phase of his life “might happen in a larger world, one beyond the horizon of my habits.”

LEARN MORE

Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, by Pierre Bourdieu

Let’s Talk about Love: Why Other People Have Such Bad Taste, by Carl Wilson

Merchants of Cool. PBS Frontline Documentary

Generation Like. PBS Frontline Documentary

7.3 Religions And Wisdom Of The World

“In the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And the compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship – be it JC or Allah, be it YHWH or the Wiccan Mother Goddess… – is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive. If you worship money and things… then you will never have enough, never feel you have enough. … Worship your body and beauty and sexual allure, and you will always feel ugly. … Worship power, you will end up feeling weak and afraid. … Worship your intellect, being seen as smart, you will end up feeling stupid, a fraud, always on the verge of being found out. But the insidious thing about these forms of worship is not that they’re evil or sinful, it’s that they’re unconscious. They are default settings. They’re the kind of worship you just gradually slip into, day after day, getting more and more selective about what you see and how you measure value without ever being fully aware that that’s what you’re doing.”

David Foster Wallace

In the ancient village of Kapilavastu, India, Kisa’s baby was not waking up. She lovingly nudged him and waited for his eyes to open, but he remained still. He had died during the night, but Kisa could not accept this. She had recently lost her husband, and her baby meant everything to her. She picked up the baby and rushed for help. The Buddha was staying nearby, so she went to him for medicine.

The Buddha, seeing that Kisa’s son had died, told her that in order to make the medicine, he would need mustard seed from a house that had not known death. Kisa rushed back to the village to find such seed. At each house she asked if they had known death, and each time she heard story after story about loved ones lost. Everywhere, the answer was the same. No house did not know death. She listened to their stories, and she started to understand.

She returned to the Buddha understanding that death is an essential element of life. Instead of trying to comfort her with the idea that all who die go to heaven, he offered instead the idea that learning to understand the true nature of the inevitable sufferings of life could bring her peace, joy, and enlightenment.

This story illustrates the profound similarities in the trials, challenges, problems and paradoxes of life that we all must face by virtue of being human. Consider the following list.

All humans:

- are born incomplete and dependent on others.

- must form social relationships to survive.

- must learn to deal with death and suffering.

- must deal with envy, jealousy, and change.

- encounter a world much bigger and more powerful than themselves and must deal with forces – physical, social, economic, and political – that are out of their control.

- must grow and change physically, emotionally, intellectually, and psychologically as they transition from childhood to adulthood, from dependency to parenthood, and on into old age and death.

The trials of life along the way are many, and often devastating. A core tenet of all of the major religions is the simple truth of unavoidable human suffering. What can be the meaning of an existence that is so fragile and temporary?

Many people assume religion is simply a superstitious belief system attempting to explain the world based on ancient understandings of the world. Religion is ridiculed for being an outdated science and justification for backwards or regressive morality. While this is certainly true for many people (not only today, but throughout human history), when we immerse ourselves into the religious worlds of different cultures and religions around the world, we also find that religion is doing a lot more than just trying to explain or moralize the world.

In this lesson we will explore what renowned mythologist Joseph Campbell calls the four “functions” of religion:

- The Cosmological Function: It provides a framework for relating to the world in a deeply meaningful way.

- The Sociological Function: It brings people together and gives them guidelines for staying together.

- The Pedagogical Function: It provides wisdom for navigating the inevitable challenges and trials of life.

- The Mystical Function. It allows people to feel connected to something bigger than themselves, giving them a sense of awe, peace, and profound significance.

UNDERSTANDING DIFFERENT WORLDVIEWS

Unlike the current Christian notion that if you believe in God and accept Christ as your personal savior, you can be saved and live for eternity in heaven, the Buddha did not ask his followers to believe in anything. Instead, he asked them to practice virtue, understanding, mindfulness, and meditation so that they could achieve enlightenment.

This difference reminds us that starting from a Western perspective on religion can lead us to miss out on a full understanding of how others see the world. In much of the world, religion is not about “belief.”

In New Guinea, there were spirits everywhere, and keeping yourself right with them was a matter of life or death. We occasionally brought an offering of pig to different spirits – the spirit of the mountain to our east, or the spirit of that grove down the hill – and invited them to feast. But these spirits were not supernatural to them. They insisted that they did not simply “believe” in them. They were just part of nature. They were not something you believed in because they were not something you would ever question. They just were. Therefore, faith and belief were irrelevant to them.

Living with them made me realize that many of the most basic questions we have about religion are culturally bounded and ethnocentric due to this focus on “belief” as the core of religion. For example, most of us would think that the proper question to ask when understanding other religions would be something like, “What god or gods do they believe in?” But this question only makes sense coming from a religious background of the Abrahamic faiths (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam). These faiths all focus intensively on faith or belief in a single omnipotent god. But what about all of the other religions – which number in the thousands – that are not based on a single god, or any god, or even on the notion of faith and belief?

Questions based on what people believe are culturally biased because they end up defining other people’s religions in our terms. Hinduism, a richly textured religion full of rituals, practices, contemplation, meditation, and stories aimed toward helping people live a balanced fulfilling and meaningful life, is diminished to become nothing more than “polytheism” - belief in more than one god. The rich world of spirits my friends in New Guinea experience, and the complex rituals and practices they engage in to relate to them, becomes nothing more than “animism” – belief in spirits.

Another problem with focusing on “belief” is that in many languages, there may not be a concept that conveys exactly what is meant by the English word “believe.” Anthropologist Rodney Needham documented several examples of this, and notes that early linguists like Max Müller found it difficult to find the concept in several languages when they started documenting indigenous languages in the late 1800s.

This problem with the word “belief” strikes at the heart of just how differently cultures may view the world. As Dorothy Lee notes so powerfully, “the world view of a particular society includes the society’s conception of man’s own relation to the universe, human and non-human, organic and inorganic, secular and divine, to use our own dualisms.” The key phrase here is, “to use our own dualisms.” Remarkably, Lee is recognizing that our most basic assumptions are culturally bounded. Other people do not make the same distinctions between the human and non-human or secular and divine that we do. They may not make those distinctions at all. She points out that the very notion of the “supernatural” is not present in some cultures. “Religion is an ever-present dimension of experience” for these people, she notes, and “religion” is not given a name because it permeates their existence. Clyde Kluckohn notes that the Navaho had no word for religion. Lee points out that the Tikopia of the Pacific Islands “appear to live in a continuum which includes nature and the divine without defining bounds; where communion is present, not achieved, where merging is a matter of being, not of becoming.”

Furthermore, the division of the world into economics, politics, family and religion is a Western construction. As Lee notes, for many indigenous peoples, “all economic activities, such as hunting, gathering fuel, cultivating the land, storing food, assume a relatedness to the encompassing universe, and with many cultures, this is a religious relationship.”

Our focus on “belief” as the core of religion leads us to emphasize belief over practice, and mind over body. In Christianity you have to believe to be saved. Westerners tend to see other religions as different versions on this theme, so we approach the study of religion as an exploration of what others believe. But the Christian emphasis on “belief” is itself a modern invention. A careful textual analysis of writings from the 17th Century by Wilfred Cantwell Smith found that the word “believe” was only used to refer to a commitment of loyalty and trust. It was the notion of “believing in” something, not believing whether or not a statement was true. In other words, according to Smith, faith in the 17th Century was a matter of believing in God (putting trust and loyalty in him) not believing that God exists. He turns to the Hindu term for faith, sraddha, to clarify what he means. “It means, almost without equivocation, to set one’s heart on.” Similarly, the Latin “credo” is formed from the Latin roots “cor” (heart) and “do” (to put, place, or give). The emphasis on belief as a matter of truth only became an issue as the belief of God’s existence became more fragile and open to question with the rise of science. As a result, most of us are used to wrestling with big ideas about the big everything, and the big question of what to believe looms large in our consciousness.

WHERE BELIEF DOES NOT MATTER