Lesson 5 Infrastructure

“We shape our tools and then our tools shape us.”

5.1 Tools And Their Humans

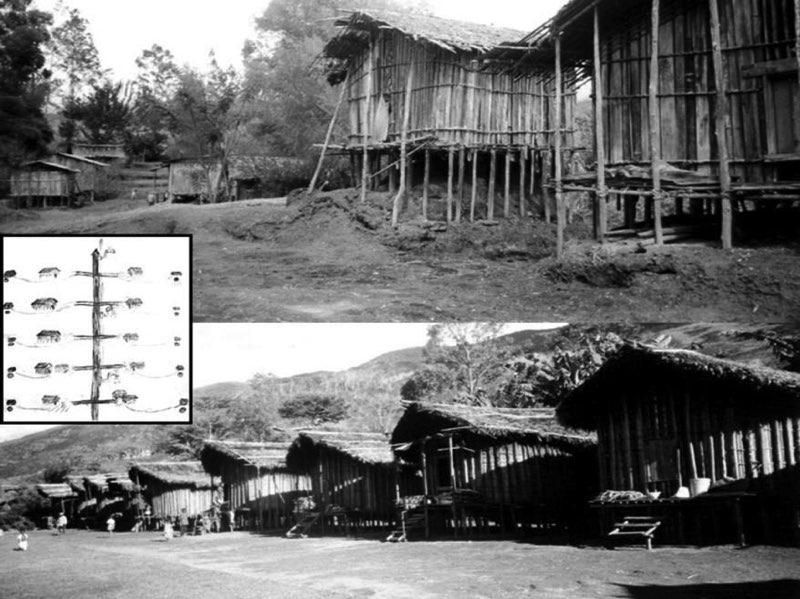

In the late 1960s, anthropologist Edmund Carpenter was hired as a communications consultant for what was then the Territory of Papua and New Guinea. Colonial administrators were seeking advice on how they might use radio, film, and television to reach, educate, unite, and “rationalize” remote areas of the territory as they moved toward independence. It gave Carpenter what he called “an unparalleled opportunity to step in and out of 10,000 years of media history.” He recorded and created some of the most remarkable events in local media history throughout the territory, such as the first times people actually saw their own photographs in Polaroids.

When I arrived in New Guinea 35 years later, I stepped off a plane onto a remote landing strip and walked one hour down a road made for cars that no cars travel, that goes nowhere, built as part of a government development project. It ends a few hundred meters from Telefolip, what was once the sacred spiritual center of the Telefomin people. I did not know that Edmund Carpenter had been there, but upon my first glimpse of the village, I immediately recognized it from a picture in Carpenter’s book. The picture, taken 35 years ago, features a movie camera sitting on a tripod in the center of the village. A Telefol man leans over hesitantly as if trying to steal a peek through the viewfinder. A young boy scurries out of the view of the lens.

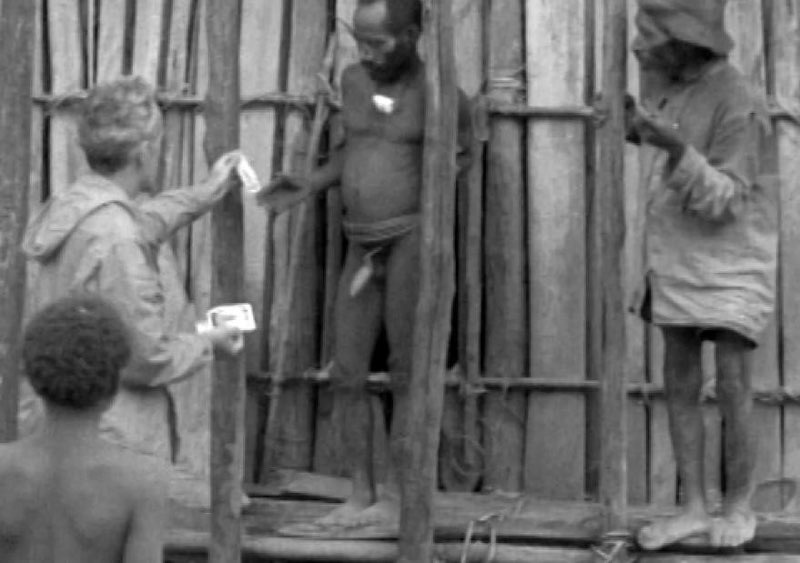

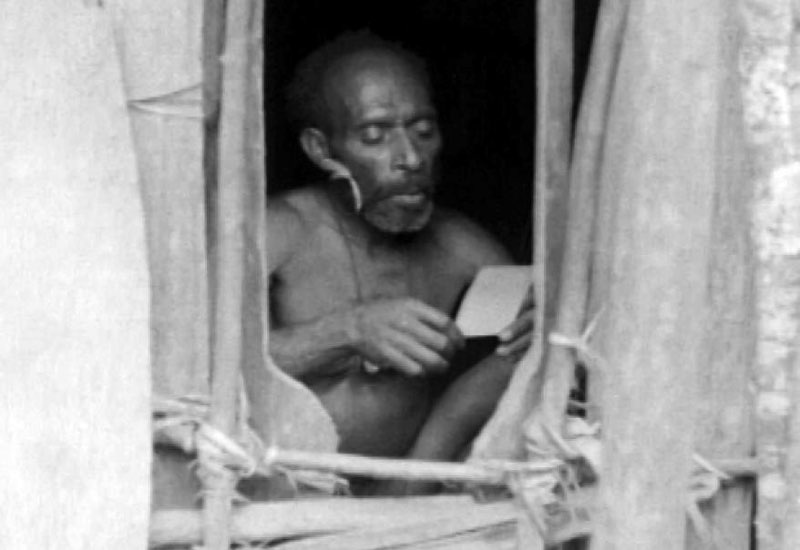

I reached out to Carpenter to find out more about his time in Telefolip, and he generously sent me copies of over 30 hours of film footage he took during his time in New Guinea. In one haunting sequence, he snaps Polaroids of two men standing outside their house and hands them the photos. Carpenter recounts that when he first gave people pictured of themselves, they could not read them. To them, the pictures were flat, static, and lifeless—meaningless. He had to point to features on the images and features of their own faces. Finally, “recognition gradually came *into the subject’s face. And fear.”

You can see it in the film footage. The man with the hat suddenly seems self-conscious about the hat. He hesitantly takes it off, hesitantly puts it back on, and finally just stands awkwardly with his hat off, staring at the image and then back to the camera that took the image.

The other man retreats to a house to be alone, staring at his image for over 20 minutes.

Carpenter describes their reactions as the “terror of self- awareness,” evidenced by “uncontrolled stomach trembling.” He describes the depths of the effect as one of “instant alienation,” suggesting that it “created a new identity: the private individual.” He argued that the Polaroid and other recording media created a situation in which, “for the first time, each man saw himself and his environment clearly and he saw them as separable.”

As an anthropologist, he understands that such a change is not likely to come from just one small event, but it participated in a whole host of other changes that were currently underway in New Guinea, such as the arrival of schools and missions, and the preparations to move toward national independence and self-government. Nonetheless, he could not shake the sense that these media forms were having dramatic effects on their consciousness.

He describes one village where he handed out Polaroids with great regret. He says that when he returned to the village months later, he didn’t recognize the place. “Houses had been rebuilt in a new style. . . . They carried themselves differently. They acted differently. . . . In one brutal movement they had been torn out of a tribal existence and transformed into detached individuals, lonely, frustrated, no longer at home— anywhere.”

Such experiences left Carpenter disillusioned about the effects of technology, especially communication technologies, on indigenous peoples, and concerned about the effects of media everywhere. “I felt like an environmentalist hired to discover more effective uses of DDT,” he lamented.

When I stepped into the village thirty-five years later, the once-thriving spiritual center of Telefol life had been reduced to a ghostly shell of what it once was. The once magnificent men’s house had recently collapsed. There were no plans to rebuild.

The other houses have all been abandoned. The residents have moved into Western style pre-fab houses lined perfectly along that government road that doesn’t go anywhere. Powerlines power up radios, televisions, refrigerators, and lights. Traditional houses have been made into “kitchens” reserved for cooking.

While powerlines had not yet reached the region of New Guinea where I ultimately settled in to do my research, many of my friends were eager for photographs of themselves and their families. I set up a simple solar panel system that gave me about two hours of power each day to write notes on my laptop, and a simple printer that I could use to print pictures. I took a picture with my brothers along with a middle-aged man, and then printed it to give to them. The older man looked at the picture and excitedly pointed to my brothers, naming them as he pointed. Then he pointed to the man in the middle, himself, and said, “Who is that?“ He saw himself so rarely that he did not even recognize himself. I would see this happen over and over again. It rarely happened with younger people, who often had small mirrors they used for shaving or decorating their faces. But many older villagers did not grow up with mirrors, and have never sought to own one.

Contrast this with our own everyday practices. How many times per day do we engage in the practice of objectifying the self into an image? Or study the self in image form? How many glances into the mirror? How many Snapchats? How many scrolls through the photo gallery on our phones, Facebook, or Instagram? It’s so often that we need not even be looking at a mirror or image. Most of us have a pretty good sense of how we look in our mind’s eye. We adjust this or that button, untuck our shirt just so, tuck our hair back behind our ear, or adjust our hat ever so slightly as we imagine how others might be seeing us at any given moment. We are constantly aware of ourselves as objects that are constantly under the scrutiny and judgment of others.

We take mirrors and photographs for granted, yet clearly they have a profound effect on those who have never encountered them. Is it possible that they also have a profound effect on us that has since gone unnoticed? What if you gave up mirrors and all images for a week, a month, or a year? Would your consciousness change?

Carpenter braved the possibility of career suicide to publish his studies on these matters. He was severely criticized by some leading anthropologists for his media experiments. He had anticipated the criticism in the book itself, admitting, “It will immediately be asked if anyone has the right to do this to another human being, no matter what the reason.”

His defense, although framed within the context of a generation ago and half a world away, should still resound with us today. “If this question is painful to answer when the situation is seen in microcosm,” he asked, how is it to be answered as millions of people are allowing new media to permeate their lives, “the whole process unexamined, undertaken blindly?”

His point is that we live a life completely immersed in technologies. But do we really understand how they shape us? We usually look at them as great comforts, wonderful conveniences, important necessities, or the source of fantastic experiences. But how do they change us? And how might we be different if we gave them up or if these technologies never existed?

“WE SHAPE OUR TOOLS,

AND THEN OUR TOOLS SHAPE US.”

This quote from media scholar John Culkin is sometimes literally true. Over long periods of time, the interaction between humans and their tools can even reshape our DNA. Over the millions of years that we have been using hand tools, there has been an evolutionary advantage to having nimble and dexterous fingers. Over time, our hands evolved an ability to manipulate objects with increasing precision, allowing us to create more precise objects which in turn create an ever- increasing advantage on more precise hand control. Our hands and our hand-tools co-evolved in their complexity. Fire is another example of a tool that changed our DNA. Fire allowed us to cook our food so that we no longer had to spend hours of our day chewing fibrous meats and tubers. Over time, we can see in the skeletal record that our jaws have become weaker and less robust since the invention of fire.

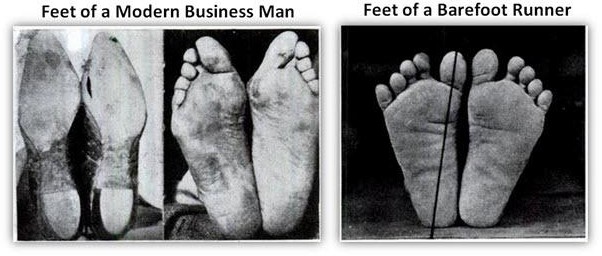

The power of technologies to literally shape our bodies is beautifully demonstrated by this famous photo published by Phil Hoffman in The American Journal of Orthopedic Surgery in 1905.

Shoes have not yet been around long enough to actually change our DNA. If you go barefoot long enough, or from a young enough age, you can also attain the amazing ability to spread your toes, engage all of your nature-given talents for balance and agility, and handle the roughest of surfaces without the aid of shoes. Similarly, coats and sophisticated climate controls like air conditioning and heating have reduced our ability to withstand cold and heat. Our comforts make us weaker.

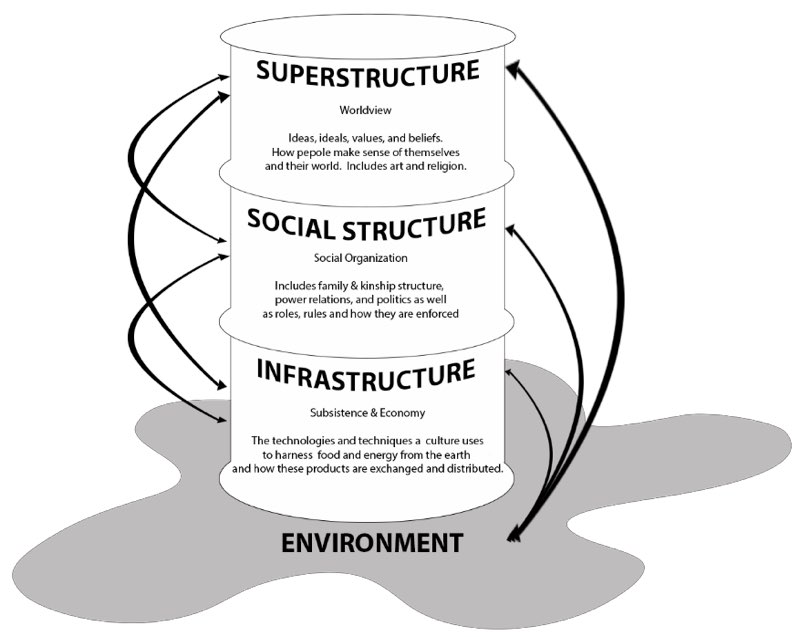

The idea that “we shape our tools and then our tools shape us” is sometimes mistaken as a claim for technological determinism, the idea that technology determines how we live, think, and act. But it would be wrong to only point out how our tools shape us. As noted in Lesson Two, cultures are complex and interrelated in such a way that no one element completely determines the other elements of the system. Instead, each element “shapes and is shaped by” another.

As we noted then, modern capitalism shapes and is shaped by modern individualism. American individualism shapes and is shaped by the American political system. The American labor market shapes and is shaped by individualism. And so on. In other words, culture is made up of a complex web of relationships of “mutual constitution” and it is this idea that we point to with the phrase, “we shape our tools and then our tools shape us.”

We can now use the “barrel model” introduced in Lesson 2 as a guide to a profound set of questions about technologies and how they might affect us. At the level of infrastructure, how does a new technology shape our subsistence and economy? What other technologies will it make more important or necessary? What technologies might it displace and make obsolete?

When one technology requires or strongly influences the adoption of another technology, we call it entanglement, and when you follow the lines of entanglement far enough, you arrive at the realization that a new technology can have far-reaching effects far beyond what was originally intended.

Take the example of clothing. In the late 1970s, the first clothes started to arrive in the New Guinea village through trade networks with neighboring clans where they had government aid posts and missions. Then, in the early 1980s, missionaries started bringing in clothes and giving them to the locals. Many people immediately converted to Christianity in hopes of receiving the luxurious goods, and missionaries worried that they might be creating “clothes Christians” – people whose faith was only worn on the skin and did not penetrate to the soul.

Though the clothes offered comfort and protection from the elements that the natives had never experienced before, they presented a host of new problems. First, they had to be washed, so they needed soap. They could not be dried effectively in their huts due to the smoke and the thatch roofs infested with insects hungry for cloth, so they needed new houses with tin rooftops. The tin rooftops required nails to hold them in place. The nails required hammers to nail them in. The tin was square and standardized, so they needed some basic geometry and trigonometry to design their new houses. Geometry and trigonometry required that they go to school. School required paper, pens, and backpacks to carry it all. And all of this required money. As it turns out, clothes are deeply entangled with a vast range of other technologies that would ultimately encourage remote New Guinea villagers to join the global economy.

There are examples of entanglement all around us. For example, if you take a walk starting from the center of my hometown of Manhattan, Kansas, you will notice that the homes near the center of town built prior to 1930 usually have large front porches and no garages. If they do have a garage it is almost always separated from the house and was built much later than the original house. The reason for the absence of the garage is obvious. The garage is a technology entangled with cars, of which there were very few prior to 1930. But what about the front porch? As we walk away from the town center and enter the neighborhoods built after 1950, suddenly the front porch is gone.

What happened? Air-conditioning. Large front porches allowed people to stay cool in the summer, and had the pleasant side-effect of creating “front porch culture” where people would sit and greet their neighbors, creating strong social bonds. The air-conditioner eliminated the need for these porches, and they disappeared, along with that sense of community. Now the most prominent feature on the front of most suburban homes is a large double-wide garage door.

This example makes it clear that technological change is not limited to technology. Technologies shape how we make a living (infrastructure), how we connect, collaborate, and interact with one another (social structure), and can even participate in a wide range of cultural changes that lead to new core values and beliefs (superstructure). To see how this can happen, let’s take a brief look at the last 12,000 years of human history.

“THE WORLD UNTIL YESTERDAY”

Humans have been hunting and gathering their food for over two million years. Viewed on that time-scale, it really is only yesterday that we were still living without most of the technologies we take for granted today. As Jared Diamond calls it, the world of hunters and gatherers is best understood as “the world until yesterday.” Up until just 12,000 years ago, all humans everywhere lived basically the same way. In the popular imagination we were hunters, and indeed we were. But the evidence suggests that we acquired the vast majority of our calories from foraging: gathering fruits, nuts, tubers, and other foods.

Our simple manner of making a living had significant effects on how we lived and what we lived for. Using simple tools such as baskets and string bags for carrying the foods they find, and bows, arrows, spears, and blowguns for hunting, a typical forager can produce only enough food for themselves and a small family. So we lived in small bands of no more than about one hundred people.

When an area was picked over, we needed to move to where the picking was better. When a herd moved on, we needed to move with them. So we lived with few possessions that might weigh us down.

This basic pattern of life was the foundation of all human life for over two million years. There were a few key inventions that changed human life over the course of these two million years; fire about 400,000 years ago, language about 200,000 years ago, and the “Creative Explosion” about 50,000 years ago that brought about the first clothing, fish nets, art, and more sophisticated stone blades. But the foundation of our survival, the way we harnessed energy from the Earth, remained foraging and hunting.

There are very few foraging cultures in existence today, but we can learn something from the few that we do observe. Most remarkable is their vast knowledge and awareness of the natural world. Wade Davis tells of a Waorani hunter in the Ecuadorian Amazon who could smell and identify the urine of an animal from up to 40 paces away. Foragers manage to find food in even the most extreme environments. The San Bushmen of the Kalahari desert in southern Africa notice small things that you and I would not notice in their desert landscape that allow them to track wild game for miles or that tell them where to dig to retrieve roots and tubers. Some tubers can be squeezed to retrieve water in a landscape otherwise devoid of this basic human necessity. At the other extreme, Inuit of the Arctic look for subtle signs on the barren white ice that indicate where a seal might be coming up to breathe. They make a small hole in the ice and wait, spearing the seal as it comes up for a breath. To you and me, it looks like these people are pulling something out of nothing.

Since their mode of subsistence can only support a small, sparse population, the social structures of these societies are simple and informal compared to the complex bureaucracies and government systems of modern states. The average person in a remote band will almost never encounter a stranger. Disputes can be settled without the need for formal laws, lawyers or judges. Social order can be maintained simply by the mutual desire to maintain good relationships with one another and to support one another as needed. With no need for formal social institutions, there are no formal leaders, no offices to hold, no authority to lord over others.

There is no need for money or marketplaces. People simply gather food and share it with others in a gift-based economy. In a gift-based economy, you benefit by giving to others when you have more than you need because you know they will give back when they have more than they need. In this way, giving a gift provides insurance against hard times. As such, people in gift economies place a high value on their relationships, which can feed them when the going gets rough, rather than material goods that are simply burdensome to carry around and may mark you as wealthy and burden you with requests for gifts from others.

This value on relationships extends to the natural and animal world as well. Hunting cultures revere the animals they hunt. They are deeply thankful for them, and offer thanks to the animals they kill for giving themselves to them. Their myths and rituals celebrate the animals and often speak of a covenant made between the hunters and their prey. For example, the Niitsipai of North America (often referred to as the Blackfoot) tell the story of a young girl who offers to marry a bison if the herd would just sacrifice themselves so her people could survive. The bison agree to this and teach her their song and dance of life, the famous “buffalo dance,” which they perform so the bison will continue to give themselves to the people in exchange for renewed life through the dance.

In this way, the tools they use take a role in shaping all aspects of their lives, from the way their societies are ordered and maintained, to their core values, religious beliefs, rituals, and knowledge.

Though they lack the technologies and material goods that we associate with wealth and affluence, Marshall Sahlins once described them as “the original affluent society.” Studies of their work habits show that foragers only work to gather food for about 15 to 20 hours per week, and this “work” includes hunting and berry-picking, activities that we consider high-quality leisure activities. Indeed, most of them do not distinguish between “work” and “leisure” at all. Their affluence is not based on how much they have, but in how little they need.

A popular story illustrates the point nicely. A rich businessman retired to a fishing village in Mexico. Every morning, he went for a walk and saw the same man packing up his fishing gear after a morning of fishing. He asked the man what he was doing. “I caught some fish to take home to my family. I’ll take a siesta while they cook this up, wake up to a nice dinner, and then pull out my guitar and sing and dance into the night. Then I’ll wake up and do it again.”

“I’ll tell you what,” the businessman said. “I have been very successful in my life, and I want to pass on all my knowledge to you. Here’s what you need to do. Fish all day, and have your wife sell the surplus at the market. Save your money and buy a boat so you can catch more fish. Save that surplus and buy a whole fleet of ships. Eventually you can invest in a packaging and supply company and make millions.”

“That sounds good,” the fisherman said. “Then what?”

“That’s the best part. You sell your business and all of your assets, buy yourself a nice little cottage on a beach in Mexico, go fishing every morning, take siestas, wake up to a nice meal and then pull out your guitar and sing and dance into the night.”

THE LUXURY TRAP

Starting about 12,000 years ago, humans domesticated plants and animals and started farming and raising livestock. Wheat, barley, pigs, goats, sheep, and cattle were domesticated in the Middle East. Maize, manioc, squash, gourds and llamas in the Americas. Taro in New Guinea. Rice, beans, and pigs in China. All over the world, simultaneously and independently, foragers shifted from their nomadic way of life and settled into growing villages to cultivate crops.

Given the apparently idyllic life of leisure, hunting, and gathering berries, why did humans start farming, build massive cities, complex technologies and burgeoning bureaucracies that ultimately sentence our youth to 13 to 26 years of schooling just to understand how to live and operate in this complex world?

Of course, the apparently idyllic life of foragers that provided ample leisure time was also riddled with the dangers of infectious disease, dangerous animals, deadly accidents, intertribal violence and unpredictable weather patterns that could reduce food and water supply. Infant mortality rates were high, and it was difficult to provide adequate care for elders if they were lucky enough to live that long.

But the life of an agricultural peasant a few thousand years later was probably worse. We know that the turn toward agriculture eventually led to the tremendous wealth of our current times, but agriculture did not produce this wealth overnight. The first farmers would have faced the same dangers of infectious diseases, animals, accidents, violence and weather of their foraging ancestors, but instead of walking around picking berries and hunting, they made a living by toiling in the fields under the brutal sun. They became dependent on a diet with fewer foods and nutrients. So we’re back to the original question. Why did we do it?

The answer proposed by Yuvaal Hurari, author of the recent best-seller Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, is that humans fell into what he calls “The Luxury Trap.” One generation reasons that it will make their life easier if they domesticate and plant a few seeds so they can establish more permanent villages. Life is good and food is plentiful for several generations. But as the carrying capacity rises, the people have more children. After a few generations, what started out as a luxury has become a necessity. Eventually the land can barely support the burgeoning population, and people have to work harder than ever to make a living.

Once humans started planting crops, the same piece of land that could support a few dozen people could support a few hundred. And once humans started irrigating that land and using animal-pulled plows, that same piece of land could support a few thousand. As Harari notes, the same area that could support about a hundred “relatively healthy and well- nourished people” hunting and foraging could now support “a large but cramped village of about 1,000 people, who suffered far more from disease and malnourishment.”

It didn’t matter that life was harder, less enjoyable, and more precarious for the agricultural peasant than it was for the nomadic forager. There was no going back. “The trap snapped shut,” as Harari says.

The broad sweep of changes that came along with the domestication of plants and animals were so revolutionary that they are often referred to as the Neolithic Revolution. Growing societies required increasingly complex institutions to manage them. Government, law, taxes, markets and bureaucracy were all formed in the wake of the Neolithic Revolution. Over time, the clear trend was toward greater production and wealth, a greater diversity of products to consume with this wealth, and a greater diversity of jobs to produce the goods, manage the wealth, and provide services to an ever-growing population. But there were negative effects as well. These farming societies were less efficient than our foraging ancestors, burning far more energy per human. Social and economic inequality rose, and we worked longer and harder than ever before. For better or worse, human society and culture was forever changed.

The changes of the Neolithic Revolution set the stage for another revolution nearly 12,000 years later: the Industrial Revolution. As revolutionary as the domestication of plants and animals might have been, most of what we take for granted today was still not in existence just 250 years ago at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. At that time, over 90% of humans were working in agriculture. Today, less than 40% of humans are farming, and the number is as low as 2% in industrialized nations like America. The Industrial Revolution ushered in an age in which more work would be done by machines than by muscle. Before the Industrial Revolution there were no cars, planes, phones, TVs, or radios. No suburbs, parking lots, or drive-thrus. No Coke, Pepsi, or Starbucks. No grades or compulsory schools. No Prozac, Zantac, or Zoloft. No Tweets, Snaps, or Finstas. No texting or emojis.

But by far the most dramatic change that occurred in the wake of the Industrial Revolution was what Harari calls “the most momentous social revolution that ever befell humankind: the collapse of the family and the local community and their replacement by the state and the market.” Prior to the Industrial Revolution, Harari estimates that less than 10 percent of the products people commonly used were purchased at the market. People were still mostly reliant on their families and communities for food, shelter, education, and employment. When they had trouble, they turned to their families. As Harari summarizes, the family was “the welfare system, the health system, the education system, the construction industry, the trade union, the pension fund, the insurance company, the radio, the television, the newspapers, the bank and even the police.”

New communication and transportation technologies enabled markets and governments to provide these services in ways that enticed people out of the security of their families and into the marketplace as individuals. People became more mobile – physically, socially, and morally. But, as Harari notes, “the liberation of the individual comes at a cost.” Our strong ties to family and community started to wither, a trend that has continued to the present day.

We are enculturated to think of technological change as good, but all of these technologies and changes have some negative side effects, and many of them can be understood in terms of Harari’s notion of the luxury trap. For example, cars were invented to make it quicker and easier to get from one place to another. In response, Americans spread out into the countryside, creating suburbs, and now spend nearly a full hour getting to and from work on average. In some cities, the average is nearly two hours, more than eliminating the supposed advantage of the car. Our communities transformed to accommodate the car. By far the largest public spaces sponsored by tax dollars are highways and parking lots. In order to accommodate cars, our communities had to spread out into the familiar suburban sprawl. In many suburbs, basic services and necessities are no longer reachable on foot, and the car, which was once a luxury, has become necessity. People rarely walk anywhere, reducing our physical health while also making it less likely for us to know and interact with our neighbors. That trap has snapped shut too.

But perhaps even more harrowing is to examine the cost of our technologies on the environment. Since the Neolithic Revolution there are now just 40,000 lions but over 600 million house cats. There are 1.6 billion wild birds on the planet but over ten times as many chickens. In total, humans and their domesticated pets and livestock make up nearly 90% of all large animals on the planet. If current trends continue, 75% of species will be extinct within the next few centuries.

Humans also produce over 300 million metric tons of plastic every year, some of which is drawn by ocean currents into the Great Pacific garbage patch, an island of trash bigger than the state of Texas.

Carbon dioxide levels continue to rise due in part to the burning of fossil fuels, raising global temperatures and leading to more extreme weather events. Sea levels have risen seven inches over the past 100 years, and in the next 100 will rise high enough to threaten major cities such as New York, Mumbai, and Shanghai.

Overall, our impact is so great that we will leave a lasting imprint on the earth. The International Commission on Stratigraphy is debating whether or not to formally declare that we have entered a new epoch in the history of the earth, the Anthropocene.

We know that we simply cannot go on living as we do without burning through our resources and disrupting climate patterns to a point that the earth may not be hospitable to human life. For these reasons, Jared Diamond once suggested that what appeared to be our greatest technological triumph, the domestication of plants and animals that set all of these forces in motion, might actually have been our greatest mistake.

A POST-HUMAN FUTURE?

We now sit at the brink of what many think is yet another revolution in human affairs. One harbinger of what might be to come is the supercomputer Watson. Developed by IBM, in 2011 they set it up to compete against the greatest Jeopardy players of all time. As the 74-time Jeopardy champion Ken Jennings fell further and further behind, he conceded the match in the final round by writing on his final answer, “I for one welcome our new computer overlords.”

Computers are becoming more powerful every moment. They drive cars, do taxes, trade stocks, manage complex budgets, play chess, write music, and even write articles we read in newspapers and online. They are even addressing problems and challenges that we struggle to comprehend. Scientists at Cornell University created a computer program, Eureqa, which can analyze large data sets to find patterns and create formulas that match the data. Eureqa has been able to discover formulas that scientists could not, and sometimes even finds a formula that works, but scientists don’t understand why it works.

The stock market is now dominated by computer algorithms, with over 75% of all trades being made by computers. Computers read headlines and make trades based on incoming news in milliseconds, before a human even has time to finish reading the headline.

As CGP Grey notes in his video, “Humans Need Not Apply,” humans have spent years creating “mechanical muscles” (large machines) to augment and replace manual labor. Now “mechanical minds” are making human brain labor less in demand. Some robots have already taken jobs. ATMs are so ubiquitous they have become invisible, but they replaced many human bank tellers. Similarly, self-checkout machines at supermarkets are reducing the demand for cashiers.

Uber already has self-driving cars picking up passengers in cities around the United States. This may be disruptive to our culture in ways that we cannot yet comprehend. Without labor costs, Uber may be able to offer luxurious and convenient rides for anybody anywhere for a cost so low that fewer people will decide to purchase a car. Just as the Internet has started to provide meta-data and signals meant only for robots, so our cities might soon be redesigned to accommodate robot drivers. But even this is too limited a vision. Self-driving cars are really part of an automated transportation and delivery system that will be able to ship everything everywhere – by land, air, and sea, a system which currently employs more people than any other major economic sector in the United States. Within the next ten years, the demand for labor in this sector could collapse.

Meanwhile, software algorithms are reducing the demand for tax professionals, lawyers, journalists and many other fields. And Watson is not only great at Jeopardy. Watson works in the medical field, and some see it as the predecessor of a future “Dr. Bot” that will provide sophisticated personal diagnoses.

Some bots are even producing creative works like art and music. David Cope, a professor of music at UC Santa Cruz, has developed a computer program that can analyze scores of music from a particular composer and then create new music that sounds like it was written by that composer. The music is good enough that it has fooled top music critics and professionals into thinking it was produced by a talented human.

In short, it appears that if you are not in the process of creating an algorithm, you might be replaced by one. And of course, even your job as a software engineer creating algorithms might not be safe. Already, many engineers create learning algorithms that are designed to write new algorithms on their own.

Some see this as the beginning of what is called “the Singularity.” The Singularity is a state of runaway technology growth, a point beyond which human thought can no longer make sense of what is happening. Futurists like Ray Kurzweil think this moment is coming soon – within our lifetimes - and it will arrive when a machine is created that is smart enough and capable enough to design and create its own replacement. At that point, the replacement will design and create its own replacement, and that replacement will create its replacement, and so on, with each one better than the last, so that within a very short period of time there will be a computer so intelligent and capable that humans will be baffled by its power. We will likely have no way of comprehending it other than in divine terms. We will probably think of it as a god.

Kurzweil also predicts that as computers continue to become smaller and faster at an exponential rate, we will soon have molecular-sized nanobots operating in our bloodstreams to battle disease. He believes that advancements such as these will allow people alive today to live well into their 100s, and he predicts that by then we will have non-biological alternatives for living matter that will replace our bodies and allow us to live forever.

He also predicts that nanobots and other technologies will enhance our cognitive capacities and allow us to enter fully immersive and realistic virtual realities. We will be able to act and move in these worlds just as we do in the real world, but these worlds could be populated by artificial intelligent beings, or other humans who have entered the world with us – much like an MMORPG – but it will feel entirely real. Noting that millions of ordinary people are already spending more time in virtual worlds than they do in the real world, Edward Castranova predicts that we may see a mass exodus to the virtual world.

All these changes bring up fundamental questions about what it is to be human. Kurzweil and his colleagues are transhumanist. They are on a quest to enhance human capabilities and overcome disability, disease, and death. It may sound crazy, but we are all transhumanist in a sense. We all support and believe in the fight against cancer and other diseases. We support and believe in treatments that allow people with disabilities to live with them or overcome them. And we do everything in our power to avoid death for ourselves and loved ones, assuming our health is good. As science and technology progress, will we eventually draw a line and say: beyond this, we let people die? Beyond this, we let people suffer with their disability or disease?

And what if we do overcome death? Will life still have the same meaning? If you were going to live forever, would you be in school right now? And what are you in school for, if all the jobs are done by robots? It could create an existential crisis in which we lose our sense of meaning and significance. Others think that this future may create a literal existential crisis, in which hyper-smart and logical robots realize that humans are a drain on the planet and reason that there is no reason for our existence at all.

Perhaps we should be grateful for our limits. Our limits may bring us pain, struggle, and suffering, but they also bring meaning to our lives.

LEARN MORE

Oh, What a Blow That Phantom Gave Me! by Edmund Carpenter

The World Until Yesterday, by Jared Diamond

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, by Yuval Noah Harari

The Second Machine Age, by Eric Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee

5.2 Mediated Culture

Four years after I first arrived in New Guinea, new media arrived in the village. It wasn’t cell phones, the Internet, or even television. It was writing, which came in the form of census and law books, sponsored by the state. Of the 2,000 people who lived in the region, only 10 could read and write effectively, and they were the ones who would try to carry out the state mandate to census the population and bring them under the rule of law.

Doing a census sounds easy. All you have to do is list people’s names in a book. The problem with doing this in these remote villages was that many people did not have formal names. They already knew everybody they encountered and usually used a relationship term to refer to them, like mother, father, sister, brother, friend, trading partner, etc. Eventually they settled on creating “census names” for which they adopted the English term “census name” into their language.

As anthropologist Roger Rouse has pointed out, the emergence of individualism as we know it today emerged from the micro-rituals and routines of what he calls the “taxonomic state,” such as censusing and mapping, which allow the state to see its citizens. As people in the village took on fixed, static names, they could start to build more stable individual identities which might one day be objectified in the form of an identity card such as a passport or driver’s license.

Inspired by the clean, straight lines of their books, the census officials dreamed of eliminating the haphazardly built traditional villages in favor of houses built along clean, straight lines, with each house numbered to match the census book. The villages would have the additional advantage of having high populations, making it easier to govern the people from a central location while also increasing their population numbers so that they would receive more funding from the state. Their lives were quite literally being made over “by the book.”

At the same time as the census came in, so did the rule of law. Until then, all disputes had been settled out in the open as affairs of the local community. The goal was not to establish guilt but to heal the relationship. When law came to the village, individuals were taken into the courthouse and measured against the letter of the law. The court is not necessarily interested in healing relationships but in determining motives, intentions, and guilt, all of which are intimately tied into the logic of individualism.

Several people resisted these changes. They did not want to move into new houses and villages. They liked how they lived and settled disputes. So the government leaders held a meeting. First, it was decided that the only people who could vote were those who could read and write. Then, they voted on whether or not they could force people to move into the new villages. The vote was unanimous, and soon after that they began forcing people to move, sometimes by burning down their houses.

The next two months were a dark time. Stress and tensions rose. Witchcraft accusations ran rampant. Angry villagers on the brink of losing their homes campaigned vociferously to preserve their homes while those in favor of the government plan tried to sell their vision of future prosperity.

But what was perhaps most remarkable about this sequence of events was how it ended. As the bickering continued, the architects of the movement looked around at the changes they had created and did not like what they saw. They felt seduced by the counts in the census book into thinking of their friends, kin and neighbors as nothing more than numbers. They felt seduced by the clean lines of their village plans into creating villages that looked clean and rational but were not very functional. The doorways all faced the same way, whereas traditionally they could position their doorway in such a way as to be open to kin but private from passersby. They started to recognize that there were important reasons why they had lived as they lived, and they felt seduced by their new technologies into imagining an alternative way of life that they ultimately found that they did not want.

This is one of the great paradoxes of technology. It empowers people in ways they have never been empowered before, and those who master the technology seem to be the ones who benefit the most. But technologies often have unintended consequences, and in retrospect, it might be those who seem most empowered by the technology who are in fact overpowered and seduced by the technology itself.

I returned to the United States soon after these events in 2003. Wikipedia had just launched. Facebook would launch the following year, followed by YouTube, then Twitter, and the whole new mediascape we now call “social media.”

Thinking about how new media had affected my friends in New Guinea, I wondered how these new media might affect us. How might we be seduced by the technology to promote changes we do not intend?

TELEVISION

When TV came into our homes over 50 years ago it immediately transformed our relationships in a way that can actually be seen in the arrangement of the furniture. Everything had to be arranged to face the box in the corner. For many people, this arrangement replaced the dining room, so instead of family dinners spent around a table, they were now spent around the box in the corner. And for 50 years, the most important conversations of our culture happened inside that box. They were controlled by the few (a few large TV networks) and designed for the masses (to win over a large audience). So they were always entertaining, even the serious ones. Our politics became entertainment and spectacle, made to fit between commercial breaks. In such ways, our media technologies shape our conversations, and taken altogether our conversations create our culture which Neil Postman grimly described in 1985 as one of irrelevance, incoherence, and impotence.

Postman recounts that the Lincoln-Douglas political debates of 1858 unfolded over the course of seven hours, with each candidate allowed an hour or more to respond in front of an attentive crowd. It was a true debate. Now we have sound-bites. If you can’t state your argument in eight seconds or less, it’s no good for TV. And in 1985 there was little you could do about it. Postman challenged his readers to imagine sitting in front of a television watching the most serious and “important” newscast available and ask yourself a series of questions, “What steps do you plan to take to reduce the conflict in the Middle East? Or the rates of inflation, crime and unemployment? … What do you plan to do about NATO, OPEC, or the CIA?” He then says that he “shall take the liberty of answering for you: You plan to do nothing.” In 1985, we had few options, and that was precisely Postman’s point. There was no talking back to the media.

All media are biased, Postman noted. The form, structure, and accessibility of a medium shapes and sometimes even dictates who can say what, what can be said, how it can be said, who will hear it, how it will be heard, and how those messages may or may not be retrieved in the future. Postman coined the term “media ecology,” noting that media become part of the environment all around us, transforming how we relate to one another in all aspects, from art to business, public politics to private family life. While any technology can have an effect on society, the change brought about by a change in media is especially profound, because a medium serves as the form through which all aspects of culture are expressed, experienced, and practiced.

A major new medium “changes the structure of discourse” Postman notes, “by encouraging certain uses of the intellect, by favoring certain definitions of intelligence and wisdom, and by demanding a certain kind of content.”

Consider Postman’s own narrative about how electronic media remade American culture. In the mid-1800s, the telegraph brought new forms of discourse to the nation. For the first time, information could travel faster than a human being and was no longer spatially constrained. The type of information was different, though, as the telegraph did not allow for lengthy exposition. People increasingly knew more of things, and less about them. Such news from distant lands could not be acted upon, so its value wasn’t tied to its use or function, but to its novelty, interest, and curiosity. This created a discourse of “irrelevance, incoherence, and impotence” that we still recognize today on television. Postman pointed out that virtually all aspects of American culture—economics, politics, religion, and even education—had transformed into entertainment. We were, to borrow the title of the book, “Amusing Ourselves to Death.”

Postman was writing in 1985, at the dawn of cable television, with its sudden onslaught of television options beyond traditional networks. In a famous novel written that year, Don Delillo describes a noxious cloud that may be seen to represent the mélange of decontextualized and disembodied information that began oversaturating our everyday experience, the phenomenon anthropologist Thomas de Zengotita simply called, “the blob.”

“What do people do in relation to the nameless, the odorless, the ubiquitous?” asks DeLillo. “They go shopping, hunt pills …” and ultimately find themselves coming together in the long lines of the superstore, “carts stocked with brightly colored goods … the tabloids … the tales of the supernatural and the extraterrestrial … the miracle vitamins, the cures for cancer, the remedies for obesity … the cults of the famous and the dead.”

Postman’s notion of media ecology reminds us that media become the environments in which we live. Humans are meaning-seeking and meaning-creating creatures, and the media we use populate our environment of meanings. It is in this environment of meanings that we search for our sense of self, identity, and recognition. “Onslaught,” a famous Dove TV commercial , demonstrates what this is like for a young girl immersed in our current media environment. It shows a young girl bombarded by a flurry of media messages telling her to be impossibly thin with perfect skin, shining flowy hair, large breasts and buttocks, and more than anything, that how she looks is her primary measure of value. The commercial quickly progresses to a future in which the girl has low self-esteem, false body-image, and an unending desire to “fix” herself through the consumption of beauty products and plastic surgery. The lyrics underscore the point, “Here it comes la breeze will blow you away/all your reason and your sane sane little minds.”

THE PROMISE OF THE INTERNET

The Onslaught video was made for the media environment of 1985 or 1995, but it was released in 2007. Large corporations no longer had a monopoly on visual media. Rye Clifton posted a remix of the commercial on YouTube called, “A message from Unilever.” He points out that Unilever is the parent company for both Dove (the creator of this wonderful program rallying against the sins of the beauty industry) and Axe (the creator of many of the more objectifying and distasteful ads that are creating the problem in the first place). Using imagery from Axe as the “breeze that will blow you away,” bombarding the young girl with objectifying imagery from Unilever’s own ad campaign, thereby reveals their hypocrisy.

Another, created by Greenpeace (2008), shows a young girl in Indonesia taking in a flurry of images of the trees in the environment around her being destroyed to clear the way for palm plantations providing palm oil for Dove products. The song is the same, but with parody lyrics, “There they go, your trees are gone today, all that beauty hacked away. So use your minds.” The video ends with the young Indonesian girl walking away from a recently cut down forest, and a subtitle that reads “98% of Indonesia’s lowland forest will be gone by the time Azizah is 25. Most is destroyed to make palm oil, which is used in Dove products.”

The video raced to over 1 million views on YouTube. Two weeks later, Greenpeace activists were invited to the table with senior executives at Unilever who then signed an immediate moratorium on deforestation for palm oil in Southeast Asia (Greenpeace 2009). Greenpeace noted that it was the single most effective tactic they had ever used.

Recall Postman’s challenge in 1985. “What are you going to do about \[major world issues you hear about on TV\]… ?” He can no longer take the liberty of answering for us. We are no longer constrained to doing nothing. We can talk back. We can create.

While the mass media of television and major newspapers were one-way, controlled by the few, and made for the masses, the Internet offers a platform in which anyone can be a creator. It is not controlled by the few, and content can be created for niche audiences. More importantly, the Internet allowed us to experiment with new forms of collaboration and conversation. Wikipedia allowed anybody anywhere to contribute their knowledge to create the world’s largest encyclopedia, just as eBay allowed anybody anywhere to sell to anybody anywhere else who had access to the Internet. Blogs allowed anybody anywhere to launch their own content platforms. YouTube allowed anybody anywhere to publish their own video channels.

In late 2007, four Kenyans came together to create Ushahidi, which means “witness” in Swahili. Ushahidi allowed people with ordinary cell phones to contribute important location-based information in times of crisis. They invented it in the chaos of riots that erupted after the Kenyan national elections. As traditional media outlets were overwhelmed and inadequate, Ushahidi allowed 45,000 people who didn’t even know each other to work together as citizen reporters to provide key life-saving information. The creators of that platform then gave it away for free online so that others could use it. After the Haiti earthquake of 2010, some Tufts University students implemented Ushahidi Haiti and started receiving thousands of messages such as, “We are looking for Geby Joseph, who got buried under Royal University.” These messages were then mapped, not on Google Maps – which was not good enough at the time – but on Open Street Maps, an open platform that allowed volunteers all over the world to trace satellite imagery to provide the most highly-detailed maps available. A U.S. Marine also sent a note to Ushahidi Haiti, to say, “I cannot overemphasize to you what the work of the Ushahiti/Haiti has provided. It is saving lives every day. I wish I had time to document to you every example, but there are too many… The Marine Corps is using your project every second of the day to get aid and assistance to the people that need it most.”

Social media platforms have played key roles in major democratic uprisings around the world. In Egypt, protestors used Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter to inspire mass protests against President Mubarak, who had used his power to silence dissent and stay in office for over 30 years. After 18 days of mass demonstrations, Mubarak stepped down.

But social media can also be used by dictators and terrorists. In the wake of failed protests in Iran in 2009, the government posted pictures of protestors and offered rewards for identifying them, effectively using the Internet to extend their control and surveillance. And for several years, ISIS has effectively used slick video campaigns, radio shows, podcasts, and high-production-quality online magazines to attract young people from all over the world to join their cause.

We are discovering that a media environment that allows anybody anywhere to produce anything anytime and share whatever they find with anyone creates major challenges for our culture. Long-standing institutions such as major newspapers are closing. Essential occupations such as journalism are dwindling as many journalism majors now move into “content marketing” jobs, creating social media content to promote brands and products.

Just as the mediascape dominated by television favored content that was entertaining (even about serious topics), so does social media. But we now live in an “attention economy” in which our lives are so immersed in media that we simply don’t have time to pay attention to it all. In the battle for our attention, content creators create shocking false headlines combined with surprising, shocking, or near-pornographic imagery as “clickbait.”

Meanwhile, platforms like YouTube and Facebook use sophisticated algorithms to predict what we might like based on our friends, previous likes, and shopping history. We end up only seeing what Facebook thinks we will want to see, and end up living in what Eli Pariser has called “filter bubbles.”

The 2016 US presidential elections magnified these problems. Democrats and Republicans lived in alternate media universes throughout the campaign season. They did not share the same basic facts about what was true and untrue, and both sides leveraged attacks at the other for producing “fake news.” And since anybody anywhere can produce anything anytime, there was plenty of fake news going around, some of which was produced by people outside the United States with vested interests in the election outcome.

What can we do? There are online petitions to encourage Facebook and Google to stop personalizing our content in such a way that creates filter bubbles, and to create technologies that stop the spread of fake news. But some scholars, such as Evgeny Morozov, worry about such online petitions. Morozov worries that true activism that involved real people organizing in the streets is now being replaced by slacktivism, easy little “likes” and clicks done from the privacy of one’s home that do not create lasting connections with real people who share similar activist goals.

Thirty years ago, scholars like Neil Postman worried that the major media corporations were using mass media to create a media environment that created a culture of irrelevance, incoherence, and impotence. Now, it seems that we might be doing it to ourselves.

THE INSTAGRAM EFFECT

Today, a new medium emerges every time someone creates a new web application. A little Tinder here, a Twitter there, and a new way of relating to others emerges, as well as new ways for contemplating one’s self in relation to others. Listing our interests, joining groups, and playing games on Facebook; sharing photos and videos on Instagram or Snapchat; swiping left or right on Tinder; sharing our thoughts, ideas, and experiences on blogs; and following, being followed, and tweeting on Twitter are not only ways of expressing ourselves, they are new ways to reflect on who we are, offering new kinds of social mirrors for understanding ourselves. And because these technologies are changing so quickly, we are not unlike those villagers seeing a photograph of themselves for the first time. We are shocked into new forms of sudden self-awareness.

Unlike those villagers who barely know their own image, most kids today have grown up with parents posting their accomplishments on Facebook and then transitioned to having their own accounts in high school. They know how to craft their best self for the camera, and they’re more comfortable than ever snapping picture after picture of themselves, crafting beautiful pages full of themselves and their likes and activities on Facebook and Instagram, and sending out little snippets of their lives on Snapchat. The era of the selfie is upon us.

I recently started noticing something strange about the profile pictures my students were using on the online portal for my course. They were all beautiful. When I face my students in person they look, on the whole, like you would expect any large group of more or less randomly selected college students to look. They look normal. On the whole, they look average. But online, they are magnificent! The women have flawless skin, bright white smiles, and beautiful hair. The men look as if they were cut right out of an adventure magazine. Upon closer examination, it becomes apparent that what I am seeing is the filter.

Most of these pictures have been lifted from their social media accounts, where one can find more of the filter. Blur effects filter out skin blemishes. Color filters make the images look professional and aesthetic. And of course, the only pictures that are posted are the ones that make it past their own critical eye, which serves as yet another filter. As a result, social media gives us a steady media stream of beautiful people doing amazing things, and those people are our friends.

And it isn’t just young people. My Facebook feed is full of images of smiling families sharing a night out, going to school, playing at parks, and competing in their latest sporting events.

Television media gave us a steady stream of beautiful people doing amazing things, and this could sometimes make us feel inadequate or that our lives were not interesting or exciting. But we could always comfort ourselves in knowing that the imagery was fake and produced by a marketing machine.

But now every one of us is our own marketing machine, producing a filtered reality for our friends to consume. Essena O’Neill rose to Internet celebrity status on Instagram, and then suddenly quit, going back to re-caption all of her old images to reveal how they had been filtered. In one picture she sits on the beach, showing off sculpted abs. “NOT REAL LIFE,” she writes. “Would have hardly eaten that day. Would have yelled at my little sister to keep taking them until I was somewhat proud of this. Yep so totally #goals.” It can be inspiring to see your friends, or other people that do not seem so different from you, looking amazing and doing amazing things. But as Essena O’Neill discovered, it can also feed into a culture of feeling inadequate.

Sometimes the consequences are devastating. Madison Holleran, a track athlete at Penn, seemed to have it all. Smart, beautiful, athletic and at one of the top schools in the world, she seemed to have it made. And her Instagram account showed it. We see her smiling as she rides piggyback on a handsome boy. We see her proudly showing off her new Penn track uniform. We see her smiling in front of a row of beautiful houses, dressed in a beautiful dress. Indeed she seemed to have it all. The last entry is a beautiful array of floating lights over a park in the city. She took it just one hour before she took her own life.

Writing about the event for ESPN, Kate Fagan noted that she talked to her friends as they scrolled through Instagram, saying, “This is what college is supposed to be like; this is what we want our life to be like.” Think of it as “the Instagram Effect” – the combined effects of consuming the filtered reality of our friends.

We have a tendency to compare our insides to people’s outsides. Even before Instagram people were filtering their beliefs and appearances to put on a good show, but social media has the potential to magnify the effect. We see other people’s lives through sophisticated filters, each image, post, and tweet quantified in likes. Seeing ourselves in a Polaroid is nothing new to us, but seeing ourselves with such a clear quantification of our “like”-ability and consuming a steady stream of filtered lives most definitely is.

“The constant seeking of likes and attention on social media seems for many girls to feel like being a contestant in a never-ending beauty pageant,” reports Nancy Jo Sales in her book American Girls. A recent study shows that there has been a spike in emotional problems among 11- to 13-year-old girls since 2007, the year Apple’s iPhone ushered in era of the always-on mobile social networking world. Since then, the “second world” of social media has become more important than the real world for many teens, as the complexities of teenage romance and the search for identity largely take place there. A 2014 review of 19 studies found elevated levels of anxiety and depression due to a “high expectation on girls in terms of appearance and weight.” Over half of American teenage girls are on unhealthy diets. The American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery reported an increase in plastic surgeries among teens due to a desire to look better on social media.

THE UNTHING EXPERIMENT

When Carpenter reported on the radical cultural changes that were in part brought about by people seeing their images in a Polaroid, he did so in hopes that we would analyze our own use of technology as well.

To analyze the effects of my tools on me, I once tried to avoid all visual images for a month. I stopped watching TV. I used an image blocker on my web browser (Wizmage for Chrome) and configured my phone to not load images. Of course, I couldn’t avoid all images. I still caught a glimpse of a billboard or product box now and then. But I lived more or less without the supernormal stimuli of photoshopped and surgically enhanced beautiful people living apparently extraordinary lives beyond any life that I could ever imagine for myself.

Within just a few days, I started to notice a difference. I found ordinary people and ordinary life much more interesting, engaging, and beautiful. Three weeks later, I was in an airport and felt a surge of joie de vivre as I entered the mass of humanity. I was surrounded by beautiful people doing extraordinary things. Every one of them seemed to have an attractive quality and something interesting to say. Just a month earlier, I would have entered that same mass of people and seen nothing but overweight, unstylish, unkempt, and unattractive people. But within a few weeks removed from the onslaught of media, my consciousness had changed.

It struck me that media puts us in a state of passive consumption. In media worlds, people and their lives exist for our enjoyment. They are objects and characters to like or dislike, rather than complex people with complex histories and experiences to engage and interact with. As I stopped seeing people as objects, I saw beauty and worth in each of them. Without the distraction of media, I freed up several hours of my day that I spent exercising, talking to friends, and being out in the world.

LEARN MORE

Amusing Ourselves to Death, by Neil Postman

Here Comes Everybody, by Clay Shirky

The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom, by Evgeny Morozov

What Made Maddy Run, by Kate Fagan

5.3 Challenge Five: The UnThing Experiment

Your challenge is to give something up and live without a key technology for at least 48 hours.

Objective: Practice the art of seeing. See your seeing as you observe how this technology might shape your assumptions. See big – how it is an integral part of a larger cultural system. See small – how it might shape our most mundane routines (or even our bodies). See it all - how our lives and culture might be different (for better and for worse) without it.

Step 1. Give something up, like shoes, chairs, or cars. Or try giving up some form of virtual communication platform for at least 48 hours, and potentially a week or more.

Step 2. Post daily updates using #anth101challenge5, reflecting on the following:

- What do you miss about using the thing?

- What have you gained by not using it?

- How have you changed? Any insights? Do you see the world or other people any differently?

Step 3. Continue the experiment until you have some significant results. (Extend the time frame or move up a level if you do not have any significant insights.)

Step 4. Use your insights to reflect on the key lesson: “We create our tools and then our tools create us.”

Learn more at anth101.com/challenge5