Unit 5 Perception

Overview

In Unit 4, we explored processes of sensation; in Unit 5 we will examine perception. Sensation and perception are different yet unified processes. The world outside of the human body is full of sensory information – phenomena we can see, hear, touch, taste, and smell. A walk around Trinity Western University can ignite your perceptions with the shadows of lofty coniferous and flowering cherry trees, the sounds of geese honking, and the warming, fragrant air of a spring morning. The body has developed two specialized mechanisms to make sense of this abundance of information – sensation and perception. The textbook (Krause et al., 2018) defines sensation as the process of detecting external events with sense organs and turning those stimuli into neural signals. Perception involves attending to, organizing, and interpreting stimuli that we sense. At the sensory level, the sound of someone’s voice is simply air particles pushing against the eardrum, and the sight of a person is merely light waves stimulating receptors in the eye. All of this raw sensory information is then relayed to the brain, where perception occurs. Perception includes organizing the different vibrations of the eardrum in a way that allows you to recognize them as a human voice and linking together the stimulation of groups of receptors in the eye into the visual experience of seeing someone walking toward you (Krause et al., 2018). Our sensation and perception affect every aspect of what we can detect and how we experience it in this wonderful world.

Topics

This unit is divided into the following topics:

- Constancies and Illusions

- Depth, Distance, and Motion

- Learning to Perceive

Learning Outcomes

When you have completed this unit, you should be able to:

- Describe the key terminology relating to sensation and perception, the eye and vision, ear, hearing, and the vestibular system, and of touch and chemical senses.

- Explain stimulus thresholds, the principles of Gestalt psychology, how visual information travels from the eye through the brain to give us the experience of sight, and colour vision.

- Apply your knowledge of signal detection theory to identify hits, misses, and correct responses in examples.

- Analyze claims that subliminal advertising can influence your behaviour, how we perceive objects and faces.

- Apply your knowledge to explain how we perceive depth in our visual field, sound localization, touch, and how to determine whether you or someone you know is a “supertaster.”

- Describe different characteristics of sound and how it correspond to perception, how the vestibular system affects our sense of balance, how pain messages travel to the brain, and the relationship between smell, taste, and food flavour experience.

- Analyze how musical beats are related to movement, and how different senses are combined together.

Activity Checklist

Here is a checklist of learning activities you will benefit from in completing this unit. You may find it useful for planning your work.

Learning Activities

- Read and Reflect – Chapter 4

- Review the Unit 5 – Course Notes (found on Course Notes tab)

- Complete the Ambiguous Figure Illusions activity

- Complete the Constancies and Illusions activity.

- Complete the Exploring Perception activity.

- Complete the A Search for Meaning activity.

- Complete the Exploring Blindsight activity

Note

The course units follow topics in the textbook, Revel for An Introduction to Psychological Science by Krause et al. (4th Edition). For each unit, please read the pertinent chapter(s) before completing the assessment for the unit.

Assessment

In this course you demonstrate your understanding of the course learning outcomes in different ways, including papers, projects, discussions and quizzes. Please see the Assessment section in Moodle for assignment details and due dates.

5.1 Thresholds of Perception

We begin Unit 5 by looking at constancies and illusions. Before moving on, it is critical that we understand that constancies and illusions actually have a lot in common - we will return to this point later after we take a look at some examples that will help us better understand this important point:

Visual Constancies

The visual constancies are some of the most powerful examples of the difference between perception and sensation. Once again, what we know or what we think we know will overcome or modify our sensory experience.

Size constancy occurs because we know the sizes that characterize familiar objects. Cars are bigger than people, buildings are bigger than cars, for example. So when we see a car and it is far away, the image of that car takes up less space on our retinas. As the car comes closer, its image takes up more space on our retinas, and we say it is getting closer. As noted earlier, when we view new or unfamiliar objects, we may have some trouble perceiving their distance from us.

Shape constancy refers to our knowledge about the shapes of objects. Again, we know that most objects do not change their shape, at least not very quickly. Perhaps that is why we are so fascinated with the recent computer graphic technique of morphing. Through that technique, objects (on film or computer monitor) can be made to appear to change their shape quickly. The last “Terminator” movie made heavy use of morphing. However, in the real world, objects tend to retain their shapes, and we know that.

Color constancy is a product of the difference between the action of the cones cells and the rod cells. Remember that the cones are responsible for color vision, and the rods for black-and- white-vision. When we are in a dark enough setting, we cannot see color because our cone cells are not getting enough light to work. They are below their threshold. But, we perceive the colors anyway. Why? Because we know what the colors should be.

So the constancies provide firm evidence that perception and sensation are not the same. Perception is more than the simple reporting of sensations. Perception is profoundly altered by our experience.

Activity: Read and Reflect

Take a moment to read through chapter 4 of your textbook and review the Course Notes for this unit. Consider how some of the themes and concepts you read about apply to what you have learned in this section.

Activity: Ambiguous Figure Illusions

Take a look at the following example - it highlights the ideas presented above…:

What do you see…?

A young woman?

An old woman?

They are both there!!!

Be prepared to share your thoughts and insights with other members of the class

Constancies versus Illusions

We could say constancies and illusions are really just different ways of looking at the same phenomena. Constancy refers to how correct you are, while illusion refers to how wrong you are. An illusion is a judgment that is not in agreement with the actual stimulus property. But constancies are also judgments that do not agree with the actual stimulus properties. Constancies help us make sense out of varied stimuli.

Both constancies and illusions illustrate the influence of top-down processing. What would it be like if these processes did not work?

Activity: Constancies and Illusions

As we have just learned, sometimes our eyes are playing tricks on us? The following sites provide some excellent visual demonstrations of constancies and illusions. Take some time to explore and connect to what you have just learned:

This website contains a number of different visual illusions:

After exploring these resources, consider the following question:

- We learn constancies and illusions from our experience with our environment. Can you think of how someone from another culture might experience different illusions and constancies?

Be prepared to share your thoughts and insights with other members of the class

5.2 Visual Perception: Depth, Distance, and Motion

Visual perception is truly an amazing phenomenon that we simply take for granted—unless of course we lose it! Imagine talking to someone born blind, and trying to describe vision. The word “see” would have no meaning, so you might explain that you could “sense” people and objects at a distance, without touching them or hearing any sounds from them. It sounds eerie doesn’t it? To a person who has never seen, your description of sight might sound a lot like parapsychology, especially like extrasensory perception (ESP), and of course, in a sense it is “extrasensory” to him or her.

Depth and Distance

The perception of depth and distance depends a great deal on the fact that we have two eyes placed slightly apart facing the same direction.

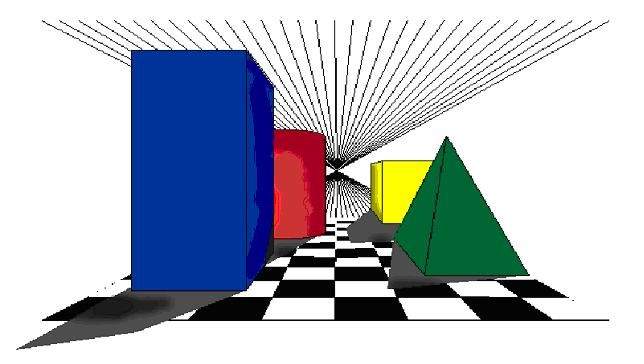

Although two eyes are important, even people with one eye can perceive depth. They use a variety of other cues. You will find this illustrated in the drawing below:

Activity: Exploring Perception

Have you ever wondered why you view objects in space in 3-dimensions? The website below gives a clear explanation of the stereo effect that result from the placement of your eyes. It also gives some interesting self-tests you can try. Take a look:

Motion Perception

The video below has some interesting demonstrations of Motion Perception; this will help to bring some of the text information to life:

After exploring the resources above, consider the following questions:

- How would you use the information on stereoscopic vision to make a photograph that would be seen in 3 dimensions or a 3-D movie?

- Which visual demonstrations from the video on motion perception interested you the most? How come?

- Our dependence on two eyes opens up additional possibilities for problems as well. How many different disorders of eye coordination can you find in a web search? In your Learning Lab, give the technical names as well as a phrase or two describing the condition in non-technical language.

Be prepared to share your thoughts and insights with other members of the class

5.3 Learning to Perceive

The difference between sensation and perception is central to this chapter. For the most part, different people’s sensations are about the same, but perceptual differences often seem to lie behind the difficulties people have with one another. Can you think of examples of interpersonal conflict based on different ways of interpreting the same situation? (Have you ever said, “He hears what he wants to hear”?) What perceptual principles seem to be involved? Do they represent differences that seem to be learned or innate? Sometimes we do not realize that our perceptions are based on learning. The different experiences we have had are a possible source of much misunderstanding in the way we see the world—both cross-culturally and even within our own culture.

Gestalt psychology emphasizes the processes by which we automatically organize our perceptions. Here are some possible ways our tendencies to group and organize our perceptions might interfere with accurate interpersonal communications:

Similarity: Does this account for our tendency to group or stereotype people into racial, occupational, or sexual categories?

Continuity: We assume that a person is essentially the same person from day to day, even though his or her life may be interrupted by many events. Is the multiple personality marked by discontinuity?

Proximity: Does this Gestalt principle explain why we are often “known by the company we keep?”

Closure: We fill in gaps in conversation (sometimes incorrectly), especially with people we know well. We may try to construct their ideas out of a fragment and then, while they continue talking, we prepare a reply to what we think they are going to say!

“Do You See What I See?”

Many people have wondered whether their sensory experiences are the same as, or different from other people’s experiences. Does red look red to you, as it does to me—or does it appear, perhaps, blue? There is no way of course, to put such a question to a conclusive test, although we can show that most people’s sensory systems are similar. We have no compelling reason to suspect that there are large differences in sensation, with the exception of persons with sensory defects such as color blindness. On the other hand, because of cultural and other differences, there are large differences in our perceptions. For example, not all cultures divide the color spectrum in the same way. Some cultures use a single label for what we call yellow, blue, and green. How might this affect cross-cultural interaction?

Activity: A Search for Meaning

Perception is a process by which we try to make sense of our world, and it is largely a result of learning. You might be able to see this in the following demonstrations.

Next, take a look at the following video. After looking at how the ear works, this video shows you a way to turn anything into a loudspeaker for those hard of hearing:

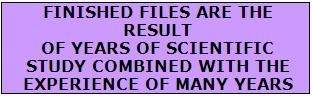

Count the “F’s” in this Statement

Answer: There are six. The meaning of the words seems to get in the way, so that most people don’t find all of the relatively meaningless “F’s.

If perception is a learned process, how would you predict that first graders would do on this test? Better or worse than college students? This simple demonstration nicely illustrates the Gestalt idea that our perceptions are “wholes,” rather than “sums of parts.”

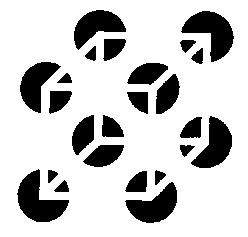

You can experience our tendency to impose meaning on our sensations in the following group of black circles with pie-shaped segments (below). Most people experience this as a cube made up of lines. But notice that the lines are really not there. We impose this simple meaning on the more complex arrangement of black pie-shaped segments:

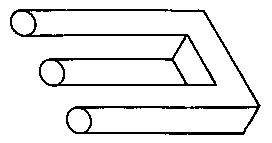

So perception is not so simple a process as we might think. We do not merely form a passive image of the world in our brains. Rather, perception is a search for meaning, as you can see by looking at an Escher drawing or an “impossible” object such as this:

You can find more Escher drawings HERE

Be prepared to share your thoughts and insights with other members of the class

Activity: Exploring Blindsight

Author and science journalist, Daniel Goleman makes note of two unusual types of blindness that illustrate the role of higher-level brain functions in sight (1985). In some types of mental disorders (formerly called hysteric blindness) mental processes prevent the person from seeing, even though the complete visual system is intact. With appropriate psychotherapy, sight will return. In “blindsight” cortical brain damage destroys the person’s experience of sight. If a person with blindsight is faced with an object, he or she will deny seeing it—the person does not even know where it is. But if the person is then persuaded to try to touch the object, he or she will reach out directly for it. The person sees but doesn’t know he or she sees.

Additionally, the following video can help support your understanding:

After reviewing the information above, consider the following questions:

- How would the difference between sensation and perception be revealed in the different experiences of two people who were given the gift of sight: one born blind and the other blind from adolescence?

- What thoughts does the information and video on blindsight raise for you concerning consciousness?

- What would it be like to have sensation but not perception?

Be prepared to share your thoughts and insights with other members of the class

Assessment

Refer to the course schedule for graded assignments you are responsible for submitting. All graded assignments, and their due dates, can be found on the “Assessment” tab.

In addition to any graded assignments you are responsible for submitting, be sure to complete all the Learning Activities that have been provided throughout the content - these are intended to support your understanding of the content.

Checking your Learning

Before you move on to the next unit, you may want to check to make sure that you are able to:

- Describe the key terminology relating to sensation and perception, the eye and vision, ear, hearing, and the vestibular system, and of touch and chemical senses.

- Explain stimulus thresholds, the principles of Gestalt psychology, how visual information travels from the eye through the brain to give us the experience of sight, and colour visions.

- Apply your knowledge of signal detection theory to identify hits, misses, and correct responses in examples.

- Analyze claims that subliminal advertising can influence your behaviour, how we perceive objects and faces.

- Apply your knowledge to explain how we perceive depth in our visual field, sound localization, touch, and how to determine whether you or someone you know is a “supertaster.”

- Describe the different characteristics of sound and how it correspond to perception, how the vestibular system affects our sense of balance, how pain messages travel to the brain, and the relationship between smell, taste, and food flavour experience.

- Analyze how musical beats are related to movement, and how different senses are combined together.